U.S. Central Command’s Gen. Frank McKenzie has no rose-colored glasses when it comes to the complex challenge of defeating the Islamic State. In fact, he knows it’s “not going to go away.”

But a total battlefield defeat of ISIS is not his goal in Iraq and Syria.

McKenzie told the United States Institute of Peace Wednesday that his aim is to prevent ISIS from again holding territory, hand over responsibility to local Armed Forces, and prevent displaced and marginalized people from radicalizing.

Not all those goals have military solutions, he said.

“The way that we contribute actually is we buy time,” McKenzie said. “If we can keep the situation relatively stable, then our diplomats have an opportunity to work the problem.”

With Iraqi diplomats entering their third month of negotiations with the U.S. regarding a status of force agreement for hosting troops in Iraq, McKenzie is confident that enough U.S. troops will remain and that Iraq will see the need.

“The underlying conditions that allowed for the rise of ISIS remain,” he said. “They continue to aspire to regain control of physical terrain.”

McKenzie said that “sustained pressure” is all that is preventing ISIS from reforming its caliphate.

CENTCOM pins its hopes that marginalized sectors of the population will find the political, economic, and security reforms they need with new Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al Kadhimi.

McKenzie also underscored a frequent refrain that U.S. troop drawdowns have coincided with the strengthening of the Iraqi security forces, which are becoming capable of confronting ISIS on their own.

“We’re seeing the fruits of the training that we’ve conducted over the past several years,” he said. “They’re good enough to begin to fight aggressively against ISIS within the physical boundaries of Iraq.”

In the meantime, there still is work to be done by American and coalition troops.

The very presence of the American military limits the scope of Iranian influence, he said. But protecting American and coalition forces from attack by Iran and Shia-linked militias this year has consumed resources, limiting efforts to target ISIS.

Leaving Iraq to Iraqis is not yet on the horizon.

“There’s going to be a requirement for us, us and our NATO and our coalition partners, to have a long-term presence in Iraq,” he said.

ISIS in Syria

The area of ISIS activity that the U.S. has the least control over is in Syria, where the U.S. is working closely with the opposition Syrian Democratic Forces.

McKenzie said there is no collaboration with Syrian and Russian forces to defeat ISIS.

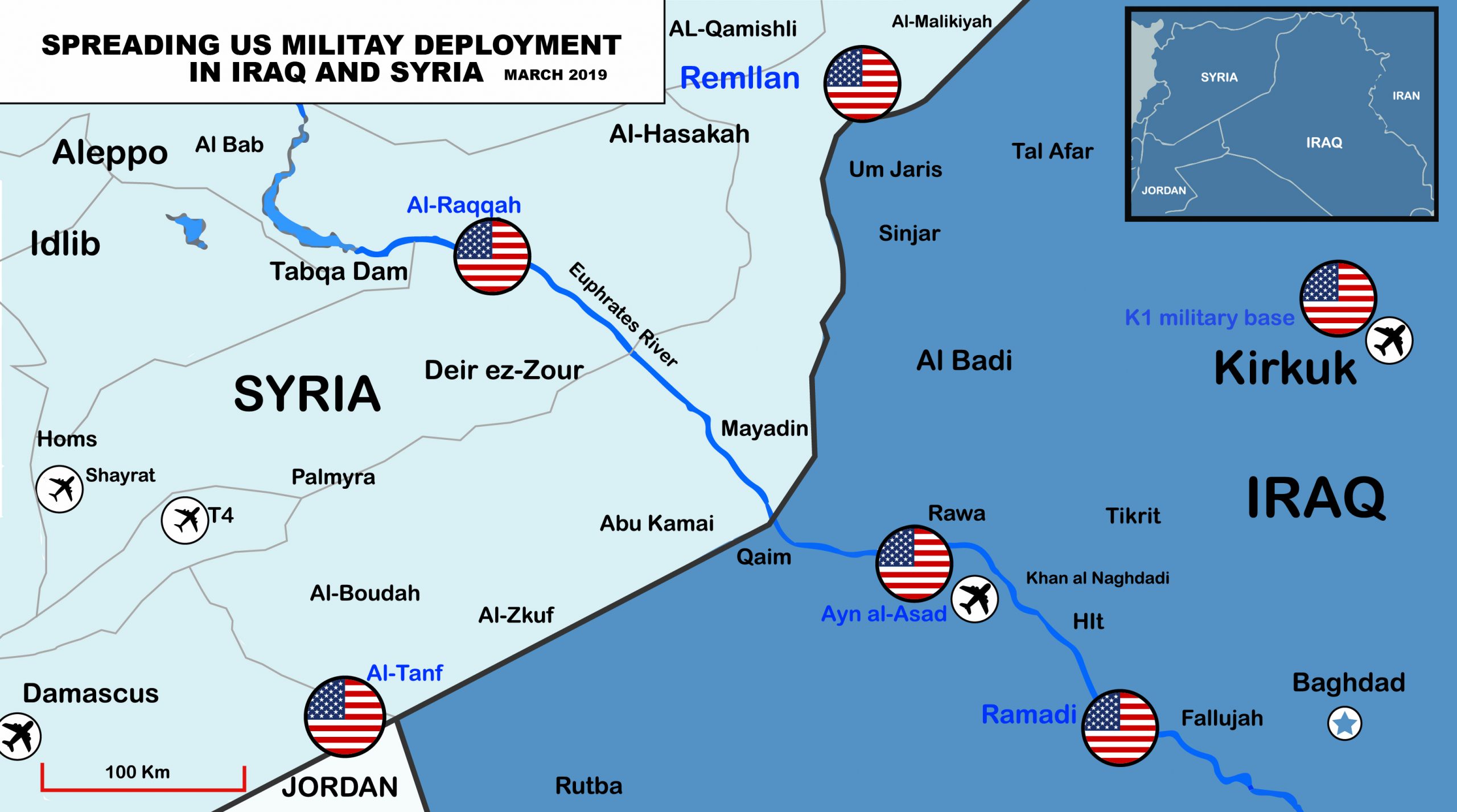

The Euphrates River bisects Syria’s northeast, creating a cone that is bordered by Turkey in the north and Iraq to the east. Turkish forces occupy the northern border area, while the U.S. maintains a troop presence east of the Euphrates River.

West of the Euphrates and beyond U.S. troop presence, there is a much bleaker picture.

“The conditions are as bad or worse than those that spawned the original rise of ISIS,” McKenzie said.

“We have a vision for stabilization,” he continued. “It may be an imperfect vision, but we have a vision. I’m not sure that out in the west, there’s any vision at all beyond violence.”

Much of the two-part USIP discussion centered on the overcrowded al Hawl refugee camp in northern Syria, which is believed to house some 65,000 displaced persons.

Many are believed to be the wives and children of ISIS fighters, while others may be ISIS fighters themselves.

Ambassador Bill Roebuck, deputy special envoy to the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS, said on an earlier panel that troops must remain to prevent an ISIS resurgence.

“The military part of it is largely over,” he said. “ISIS remains a significant threat. And that’s why the military presence is still there, and that’s why the coalition remains engaged to prevent ISIS from resurging.”

Maj. Gen. Alexus G. Grynkewich, the director of operations at CENTCOM, said that reintegrating all the displaced persons from al Hawl may not be possible.

“Some of the individuals in that camp, especially al Hawl, are not just family members associated with ISIS proper,” he said. “Some of them are ISIS fighters.”

A deteriorating humanitarian situation, including a recent outbreak of COVID-19 at the camp, coupled with reluctance by many countries to accept the repatriation of their citizens, has prevented the international community from closing al Hawl.

The result could be a devastating reconstitution of ISIS in the future, McKenzie explained.

“Unless we find a way to repatriate, to de-radicalize, to bring these people that are at grave risk in these camps back … we’re buying ourselves a strategic problem 10 years down the road, 15 years down the road, and we’re going to do this all over again,” he said.

McKenzie described two timelines, a military timeline measured in days, weeks, and months and a radicalization timeline that happens over years.

“Young people grow up, and we’re going to see them again unless we can find a way to turn them in a way that will make them productive members of society,” he said. “If you keep a lot of people there, bad things are gonna happen in terms of radicalization.”

McKenzie held out hopes that U.S. diplomats could convince countries to accept their citizens (and former fighters) for reintegration and possible prosecution.

“Al Hawl arguably is one of the worst places in the world,” he said of the possibility of returning displaced persons to Iraq. “But I’m not wearing rose-colored glasses.”