Thanks to George Orwell, the year 1984 immediately conjures up unpleasant associations. But hindsight is, ahem, 2020, and those of us old enough to remember the year can tell you it was actually pretty great. America was finally busting out of an economic slump. The Cold War loomed large, but President Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher were at the height of their popularity. On the cultural front, it’s long been a parlor game for music critics to try and argue what year was the best for music, and 1984 has always been a leading contender. In the introduction to Can’t Slow Down: How 1984 Became Pop’s Blockbuster Year, author Michaelangelo Matos notes that as early as 1989, David Marsh, one of the elder statesmen of U.S. music critics, was making the case that 1984 was an “explosion … of the greatest group of American pop singles of the decade.”

As for albums, Prince’s Purple Rain, Madonna’s Like a Virgin, Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the U.S.A., Cyndi Lauper’s Girls Just Want to Have Fun, the Cars’ Heartbeat City, U2’s The Unforgettable Fire, and Van Halen’s 1984 all came out that year. New wave bands such as the Eurythmics, the Thompson Twins, A-ha, and Wang Chung released a slew of catchy hit singles. And it was a phenomenal year for one-hit wonders, such as Nena’s “99 Luftballons,” John Waite’s “Missing You,” Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s “Relax,” Rockwell’s “Somebody’s Watching Me,” and Corey Hart’s “Sunglasses at Night.”

It was also the pivotal year in which rap transitioned from a novelty to the kind of gritty hip-hop that earned critical respect as well as commercial success. Run-DMC released its first record, and a brand-new label named Def Jam released its first two singles, which were by the then-unknown Beastie Boys and LL Cool J. Heavy metal began to crossover to the pop charts in a big way. Bands such as Quiet Riot and Twisted Sister, whose respective songs “Cum On Feel the Noize” and “We’re Not Gonna Take It” became MTV staples in 1984, paved the way for the hair metal that defined the rest of the decade. Meanwhile, an underground thrash band from Oakland, called Metallica, made its major-label debut in 1984 with Ride the Lightning. It would eventually sell 6 million copies.

If you don’t insist on being technical, a number of monster albums released in late 1983, such as Huey Lewis and the News’ Sports and Duran Duran’s Seven and the Ragged Tiger, should really be considered albums that defined 1984. (Heck, the biggest-selling album of 1984 was Michael Jackson’s Thriller, released in November 1982.) It was a monster year for film soundtracks in general, notably Footloose, which had several huge hits, and Ray Parker Jr.’s inescapable “Ghostbusters,” and featured a few smash soundtrack hits, such as Phil Collins’s “Against All Odds” and Stevie Wonder’s “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” that are much better remembered than the forgettable films they appeared in. It was even a great year for films about music. This Is Spinal Tap came out in 1984, as did the Talking Heads’ Jonathan Demme-directed Stop Making Sense, a serious contender for the best concert film ever made.

It’s also true that 1984 was a great year for critically beloved artists — think Leonard Cohen’s Various Positions (aka the “Hallelujah” album) — as well as for influential indie and alternative stalwarts such as Echo and the Bunnymen, the Smiths, the Replacements, the Minutemen, R.E.M., Depeche Mode, and Husker Du, which all released seminal records that year. These artists, however, occupy a small role in public consciousness compared to the stuff at the top of the ‘80s pop charts. The last three decades have seen snobbish music critics cranking out a flurry of tomes about every semi-obscure post-punk and indie scene you can think of, while largely ignoring ‘80s pop music, even though, as Matos points out, in every major city in the world, bars and clubs still regularly host “‘80s night.”

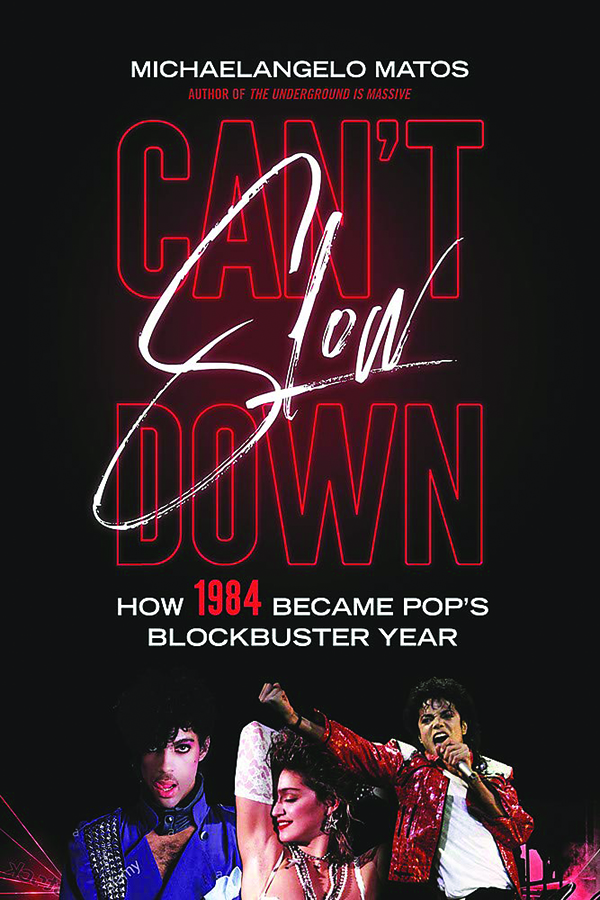

That’s where Can’t Slow Down comes in. While there have been many individual artist biographies, there is precious little available in the way of literary overviews of ‘80s pop music as a whole. Though it’s specifically focused on 1984, Can’t Slow Down does a good job of painting a picture of the broader forces that made 1984 a breakout year that sonically defined the decade.

Rock dominated the airwaves through the ‘70s, as radio programmers became increasingly less adventurous. Pop radio was playing dinosaurs such as Led Zeppelin and the Eagles into the ground, and the only new songs allowed on the air were bombastic midtempo power ballads by newer bands such as REO Speedwagon and Styx. Throw in a dismal economy and some cocaine-fueled music industry bankruptcies, and the music business was in an undeniable slump, artistically and commercially.

With Thriller, Jackson and Quincy Jones intentionally tried to bust out of radio’s rigid formatting. For instance, when Eddie Van Halen was called in to do the solo on “Beat It,” the goal was to get Jackson on rock radio as well as the pop and soul charts. It worked spectacularly well, and a year later, other genre-bending artists such as Prince were burning up the charts in ways that hadn’t seemed possible for black artists a few years earlier (Matos also mentions MTV’s early and shameful reticence to play black artists, which started to change in 1984). The cross-pollination freshened up the sound of rock. When Eddie Van Halen brought in prominent synthesizer riffs on 1984, Matos notes that contemporaries compared the album’s big hit, “Jump,” to Prince, which wasn’t inapt.

Technologically, the year was a big transition for the music industry. 1984 was the first year cassettes outsold vinyl records, and the compact disc had just been commercially introduced in 1983. Digital technology was starting to alter the sound of music dramatically. Increasingly ubiquitous studio effects processors made things such as gated reverb on drums a defining sound of the ‘80s. The advent of MIDI, or the musical instrument digital interface, in 1983-84, a computer protocol for letting different keyboards and studio equipment interface, also made synthesizers, sequencers, and drum machines much easier to program, allowing them to become staples of pop music going forward.

In addition to detailing these larger forces efficiently, Matos gives a very comprehensive overview of the entire 1984 music scene. One of the book’s astounding takeaways is just how much was going on musically that year, and Matos does a good job of picking small details and episodes that speak to larger developments. He seemingly leaves no stone unturned, detouring not only into hip-hop and country but into major developments in Latin music, as well.

Matos’s facility in covering so many disparate scenes and genres is where many of Can’t Slow Down’s more interesting insights come from. In his chapter on Nashville in 1984, Matos notes that Lee Greenwood’s hoary-but-beloved “God Bless the U.S.A.” came out the same week as Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” The two songs were embraced for similar patriotic reasons, though lyrically, they are poles apart, and Springsteen still protests that his song is misunderstood. Either way, this fun fact is a nice little synecdoche for the country’s cultural divides.

While the book jumps around quite a bit, Can’t Slow Down stays narratively grounded by dwelling just long enough on major artists such as Jackson, Lauper, Madonna, and Prince. Matos is also to be commended for avoiding the tendency to let either enthusiasm or pretentious prose get in the way of telling his story.

But that doesn’t mean the book is boring or lacks personality. Boy George and Culture Club were given the Best New Artist award at the 1984 Grammys and created quite a stir when Boy George accepted the award by saying, “Thank you, America. You’ve got — you’ve got taste, style, and you know a good drag queen when you see one.” Matos dryly observes, “The [awards show] director, in a moment of semiotic genius, cut to the country-gospel family group the Gatlin Brothers Band in the auditorium. They looked puzzled.”

Can’t Slow Down is suffused with such entertaining and illuminating vignettes, and unlike a lot of music books, it doesn’t trade in gossip or legends. (The book has a whopping and useful 71 pages of citations.) Not only does Can’t Slow Down start to fill in a gaping hole in music history, it sets an awfully high bar for the future books on ‘80s music that will hopefully follow.

Mark Hemingway is a writer in Alexandria, Virginia.