Hillary Clinton’s second attempt to secure the Democratic presidential nomination always had the makings of a coronation. Serious challengers dutifully remained on the sidelines, donors lined up to fill her coffers, and the primary was deliberately structured in her favor.

But even seasoned soothsayers failed to foretell the phenomenon that was Bernie Sanders’ progressive insurgency.

When the socialist senator announced his White House bid in April 2015, news media reacted not with mild derision but with delight, for it held out the prospect of diversion away from two stolid primaries producing a dreary Hillary Clinton-vs.-Jeb Bush general election.

In a year of upheaval, Clinton nevertheless managed eventually to become her party’s standard-bearer, but she did so not by exciting the Democratic base but only by appealing to the Democratic establishment’s preference for stability — and desire for victory.

The need to unify behind a known quantity was shaken in May, when Donald Trump demolished his last rivals in the GOP primary before Clinton had put away her own persistent rival.

Fewer than 5 percent of voters could even recognize Sanders at the beginning of his campaign, more than 50 points adrift of front-runner Clinton. But his blend of upbeat progressivism, delivered with a gruffness that made it sound less fanciful, quickly forced Clinton to confront the gap between her assets as a candidate and the mood of the electorate.

Even seasoned soothsayers failed to foretell the phenomenon that was Bernie Sanders’ progressive insurgency. (AP Photo)

Clinton’s team at first painted Sanders as not really a Democrat, as insufficiently committed to party principles on touchstone issues such as gun control. But when this got them nowhere, they switched 180 degrees and argued that his proposals were too radical.

She eventually settled on a label for herself, “A progressive who likes to get things done,” which suggests she is as left wing as Sanders, but has a better grasp of what is possible.

Clinton’s positions weren’t less liberal, just more pragmatic than than those driving the base into Sanders’ camp. The implication, too, was that Sanders wouldn’t keep his promises and so couldn’t be trusted.

Sanders exploited some of what had been Clinton’s greatest strengths, such as her deep connections to the party apparatus and her longevity on the political stage. This tactic proved effective, stealing victories in state after state away from President Obama’s chosen heir.

In the process, Sanders pulled Clinton leftward on several key issues and exposed many weaknesses of Clinton’s that will be exploited by Trump in the general election.

Difficult beginnings

Shortly after Clinton conceded the 2008 primary to Obama, a post-mortem penned by ABC News’ Rick Klein in June of that year argued the former first lady’s failure could be traced to a single “faulty assumption” made by her campaign “that inevitability itself could underpin the rationale for a presidential candidacy, even in the face of a deep Democratic desire for change.”

In a year of upheaval, Clinton nevertheless managed eventually to become her party’s standard-bearer. (AP Photo)

The Clinton team entered the race in mid-April 2015 eager to show it had improved from its failed efforts nearly eight years earlier. The campaign focused on building a strong staff presence in the early states to target specific voter groups while placing hundreds of field staffers across all 50 states, including many operatives who had migrated from the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee.

Doug Thornell, a Democratic strategist, said Clinton’s camp applied lessons it had learned in defeat to its 2016 primary strategy.

“In 2008, it always seemed like a rollercoaster, but in 2016 they bought into a plan and they executed it,” Thornell said. “Yes, there were rocky moments, but they weren’t blind-sided.”

For Clinton, those rocky moments started early. Just weeks before her nascent campaign began in earnest, the New York Times unleashed a controversy that would haunt her for the rest of the primary, disclosing that she used a private email server for official communications while secretary of state.

The story immediately aquired the suffix, “gate,” which is reserved for scandals big and complex enough to suggest they could drag on a long time and cause lasting damage. It instantly put Clinton in a defensive position at the very moment she was about to jump into the race.

Grant Reeher, a political science professor at Syracuse University, said Clinton’s decision to delay her campaign announcement until mid-April 2015 cemented her status as the automatic front-runner.

“Her waiting to officially enter the race even though most people thought that she was going to run … It really seemed to have the effect of freezing the field in a way that really worked to her advantage once she did go ahead and announce,” Reeher said.

“Holding off on the announcement that she was in really seemed to keep people out,” he added.

Clinton started her campaign by uploading a YouTube video of ordinary members of the public talking about things they were getting ready to do, from Hispanic brothers preparing to open their own business to a gay couple gushing about their forthcoming wedding.

“I’m getting ready to do something, too,” Clinton said near the end of the clip. “I’m running for president.”

The low-key launch mirrored the lukewarm enthusiasm for her candidacy in those early weeks, stirring up enough discontent among Democrats to oblige her to undertake a second campaign launch.

Her team had planned to start slowly, organizing a slate of small events in early voting states and limiting Clinton’s interaction with news media. But as scrutiny and controversy grew over her use of personal email for sometimes classified official business, Clinton’s campaign staff put together what amounted to a do-over launch in June.

This time, Clinton leaned heavily on the historic nature of her quest to become the first woman president, ditching the sterility of a pre-made video for the energetic tableau of a rally flanked by the New York City skyline.

A tough summer

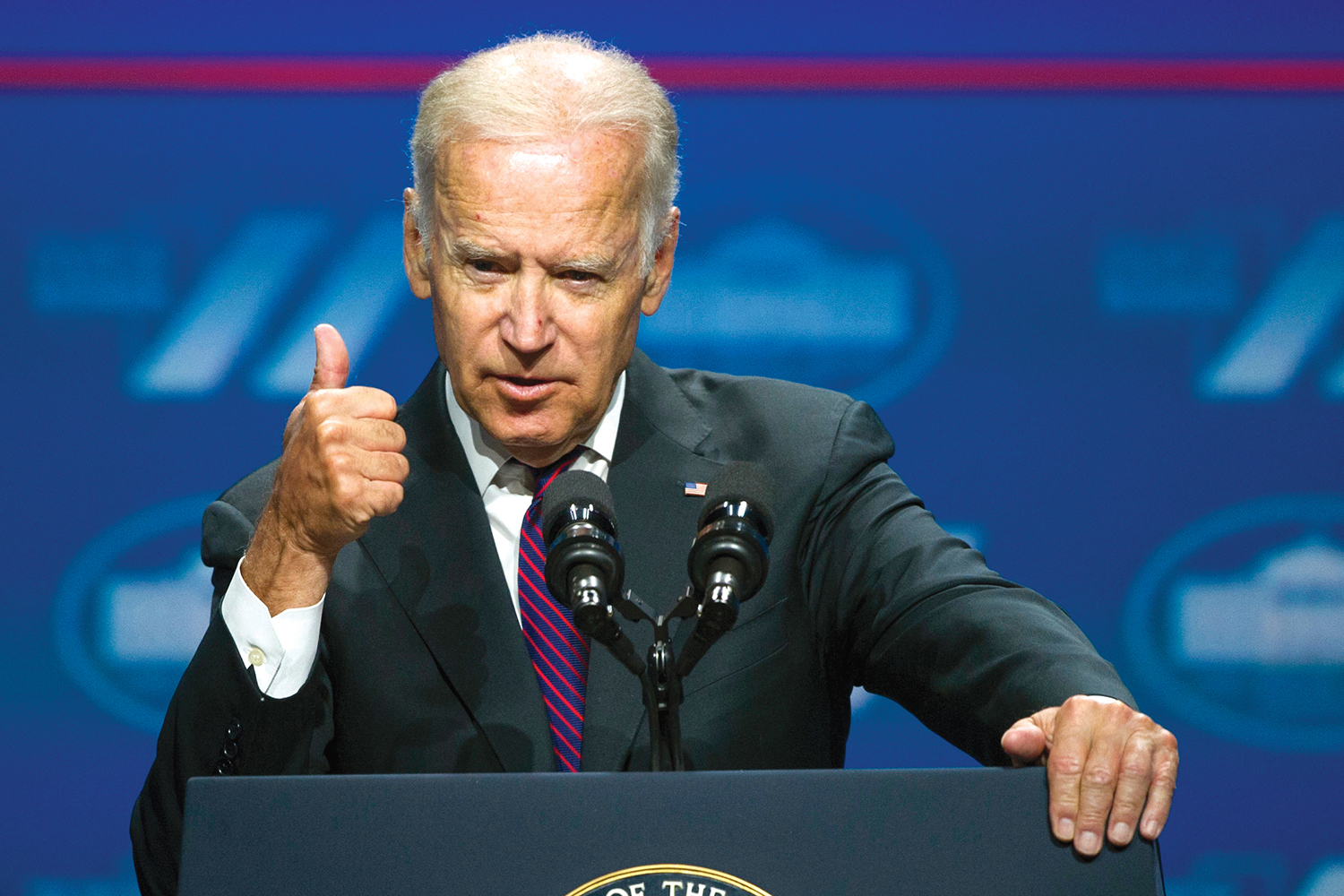

By summer’s end, there were strong rumors that Vice President Joe Biden would mount a challenge for the nomination, and this eroded Clinton’s support among the Democratic base.

The Clinton camp feared Biden would be a fierce opponent if he joined the fray. It is true that he was, naturally, still grieving for his son Beau, who died of brain cancer in spring 2015, but the vice president was clearly testing the political waters by allowing speculation to grow unchecked that he was about to jump in. A super PAC was even set up to draft Biden into the race.

The Clinton camp feared Biden would be a fierce opponent if he joined the fray. (AP Photo)

Roughly half of Democrats wanted Biden to run by early August last year. His growing popularity among primary voters came at an inconvenient time for Clinton as new details about her private email use emerged, including the fact that top secret information had probably passed through her unsecured personal network.

News that the FBI had opened an investigation into her conduct, that agents had seized the server, and that the House Select Committee on Benghazi was pushing Clinton to testify about her handling of the 2012 terror attack on Benghazi all amplified calls for Biden to consider a presidential bid.

Many had initially expected Sen. Elizabeth Warren to be Clinton’s primary opponent, and the Massachusetts progressive was the subject of several draft attempts by the powerful liberal website MoveOn.org.

But when Warren repeatedly declined to run, Sanders’ candidacy took on a new intensity. His talk of a rigged economic system caught fire with Democratic voters, and within days of announcing his campaign he had overtaken former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley, former Virginia Sen. Jim Webb and former Rhode Island Gov. Lincoln Chafee.

Sanders’ rise and the specter of Biden’s will-he-won’t-he bid made summer 2015 complicated for Clinton.

She was particularly vulnerable during that period, Reeher said, adding, “Had Biden gotten in, he would have been the nominee.”

He pointed to the email controversy as a factor that weakened Clinton significantly.

“[Clinton] had already developed a public reputation for this problem of secrecy, trust, her style in handling critiques and questions. It wasn’t some new kind of thing in terms of the problems with Hillary Clinton as a candidate,” Reeher said. “It fit right in the wheelhouse of the main thing that she’s always struggled with.”

Beyond the triple threat of Sanders, Biden and emails, the ropeline campaigning required of candidates in Iowa and New Hampshire exposed Clinton’s weaknesses as a retail politician.

Her average lead over Sanders dropped below 15 points in polls by September last year, a freefall of more than 40 points from just a few months earlier. Sensing an opportunity, Biden supporters raised their efforts to draw the vice president into the race to fever pitch.

Some Democrats say Biden’s long public flirtation with a primary challenge shaped Clinton’s campaign strategy.

“Although the clearest influence came from Bernie’s run, one thing that Joe Biden’s potential candidacy had was a lot of integrity and honesty and heart,” a Democratic bundler and former leader of Draft Biden, a pro-Biden super PAC, told the Washington Examiner.

“He wasn’t poll-driven or afraid to lead on an issue,” the fundraiser added, “so I think Hillary took something from that. Democrats realized we need more heart in Washington and in the political system.”

Bouncing back

The tide turned in October when Clinton was able to allay party leaders’s fears that she was becoming unviable.

First, Biden ended speculation by announcing he wouldn’t run. But he vowed to participate in the political debate and devote himself to preserving his party’s hold on the White House.

The very next day, Clinton appeared before the Benghazi committee for a highly anticipated hearing about how she shaped the misleading administration talking point that falsely blamed the 2012 Benghazi terrorist attack on a YouTube clip.

She gave 11 hours of testimony without stumbling, sapped the committee’s credibility, and allowed her supporters to claim that she lifted herself above suspicion of wrongdoing in the Benghazi scandal.

Clinton’s poll numbers quickly rebounded.

Brad Bannon, a Democratic strategist, said October was a “great month” for Clinton. “Everything fell her way then,” he said. “She was kind of on the ropes with Bernie at that point, but the Biden withdrawal and the Benghazi hearing, her numbers jumped like crazy. And Bernie was kind of playing catch-up all the way after that.”

Sanders abandoned his most powerful weapon on the battlefield when, in a televised debate, he said voters were “sick and tired” of “hearing about [her] damn emails.”

In doing so, he empowered Clinton to dismiss the controversy as a right-wing smear and freed her from having to address the issue among Democratic voters.

Early state trouble

Sanders’ supporters demonstrated their surprising power during the first-in-the-nation Iowa caucuses this January, resulting in a victory for Clinton so narrow that few could argue with Sanders when he called it a “virtual tie.”

The Vermont senator rode into New Hampshire on a new wave of momentum after his strong showing in the Hawkeye State. Although he was already expected to win New Hampshire because it was his neighboring state and similar to Vermont, Sanders’ victory there bolstered the perception that Clinton’s campaign was faltering.

Sanders had won a decisive majority of the primary vote in New Hampshire, but walked away with about the same number of delegates as Clinton because she scooped up the superdelegates (AP Photo)

Sanders raised $42.7 million after his New Hampshire win, beating Clinton’s haul by more than $10 million in the weeks that followed.

“Everyone dug in after New Hampshire. They knew it would be a long fight,” Thornell said. “But [the Clinton campaign] had the apparatus to do that across the country. She had built a national campaign that helped her weather the loss in New Hampshire.”

Despite the friendly demographic territory that lay ahead for Clinton in South Carolina and the Bible Belt, a damaging narrative was beginning to take shape among her Democratic detractors.

Sanders had won a decisive majority of the primary vote in New Hampshire, but walked away with about the same number of delegates as Clinton because she scooped up the superdelegates — party leaders free to support whichever candidate they wanted.

Sanders’ crusade against superdelegates gained little traction beyond his base of supporters because it was a “process argument,” Bannon said, adding, “People outside of Washington don’t follow the process or care about the process the way political insiders do.”

Clinton sapped Sanders’ momentum with a seven-state sweep on Super Tuesday, padding her lead with pledged delegates from victories in Alabama, Georgia, Arkansas, Massachusetts, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia.

But the idea that party elites were working to ensure Clinton clinched the nomination regardless of primary and caucus outcomes had become a central theme of Sanders’ campaign. It allowed him to present each loss as evidence of the establishment’s plot, thus blunting the impact of her successes.

As the race shifted to the Midwest in late March and early April, Sanders’ long-shot bid reached its zenith. He racked up wins in Idaho, Utah, Alaska, Hawaii, Washington state, Wisconsin and Wyoming. He even managed to notch a surprise victory in Michigan.

But although these gave Sanders’ supporters reason to believe their candidate was rising above Clinton, the relatively low delegate prizes in those states kept Sanders from making serious inroads into her lead.

By the time the New York primary arrived on April 19, momentum had tilted back in Clinton’s favor for good.

Sanders’ influence

Sanders’ overwhelming popularity with young and independent voters forced Clinton to change her positions on trade, gun control and the Keystone Pipeline, among others.

Sanders’ overwhelming popularity with young and independent voters forced Clinton to change her positions on trade, gun control and the Keystone Pipeline, among others. (AP Photo)

She was compelled to amp up her rhetoric against Wall Street while Sanders drew attention to her financial ties to big banks with his dovetailing focus on campaign finance and financial sector reform.

“Because of Sanders’ campaign, in order to win the nomination, Clinton had to move out of the center and move into a much more progressive mold. She was pushed, sometimes not willingly,” said Hank Sheinkopf, a Democratic strategist.

“She wanted to win the nomination, and she needed the Barack Obama vote,” he added.

Sheinkopf said Clinton’s eventual decision to pitch herself as a “progressive who likes to get things done” chipped away at her opponent’s credibility among the more liberal wing of the party.

“By defining herself that way, she really damaged Bernie Sanders badly,” he said. “What he was doing didn’t seem real and she seemed pragmatic.”

Sanders’ refusal to exit the race after Clinton’s lead became insurmountable delayed her pivot to Trump, even as the last of more than a dozen Republican rivals bowed out in early May. Meanwhile, the FBI’s decision to not recommend charges over her private email use, while not ending the controversy, removed the last vestiges of the admittedly remote possibility that she would be prosecuted.

Reeher suggested Trump’s emergence actually boosted Clinton’s prospects.

“The main enthusiasm for her campaign is that she’s running against Donald Trump,” the political science professor said. “Before that became the case, there was an enthusiasm problem.”

Some of the characteristics that drove Democratic voters’ ambivalence toward Clinton may, in the end, serve her well against the unpredictable real estate mogul.

Bannon pointed as an example to the constant controversies that have surrounded the former first lady for decades, often to the delight of her Republican critics.

“She can take a punch. Every time she manages to fight through it and do what she’s going to do,” he said.

“To many people, that describes the job of president.”