It’s hard to know what to think about Russiagate. James Jesus Angleton, the legendary Cold War head of CIA counterintelligence, liked to refer to intelligence work as “the wilderness of mirrors,” and the phrase works well as a description of the events surrounding the FBI’s counterintelligence investigation into the Trump campaign — and the ways in which that investigation gradually mutated into the theory that Trump was an agent of a foreign power.

What we know is disturbing enough: that members of the American intelligence community used uncorroborated opposition research (the “Steele dossier”) as a predicate for spying on President Trump and his associates. Through selective and often illegal leaks to the media, these agents — working alongside de facto allies that included Democratic operatives, shady bit players from the intelligence demimonde, and Fusion GPS, the opposition research firm retained by the Clinton campaign — at first tarred Trump as a “de facto agent” of Vladimir Putin and then attempted to sell the nation on the theory that Trump colluded with Russia to rig the 2016 election. That lie, and the atmosphere of hysteria that accompanied its spread, claimed the scalp of Trump’s first national security adviser, Michael Flynn, and led to the opening of Robert Mueller’s special counsel investigation, a two-year wild goose chase that shadowed most of Trump’s first term in office.

What we don’t know is how deep the rabbit hole goes. There are still seemingly contradictory facts to be sorted through and plenty of unsolved mysteries. But at the center is a question: Was it a mistake or a conspiracy? That is, was the FBI investigation and the ensuing scandal the result of shoddy work by patriots who thought they had good reason to suspect Trump was colluding with Russia? Or was it something more sinister — a concerted effort to tilt the 2016 election and, after Trump’s victory, to delegitimize him and ultimately remove him from office?

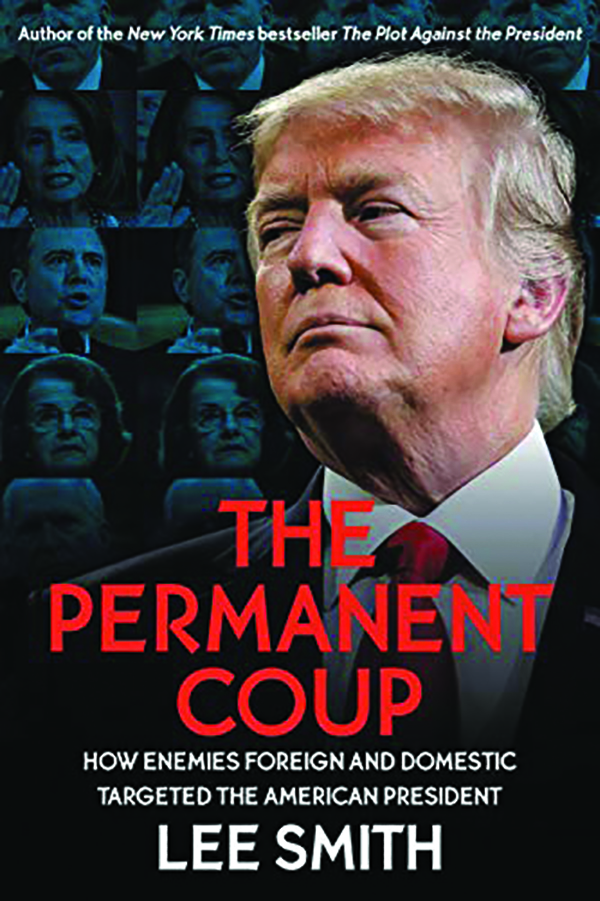

The second possibility is at the heart of The Permanent Coup, a new book by Lee Smith, an investigative reporter primarily affiliated with Tablet and the author of last fall’s The Plot Against the President. Smith’s own deep suspicion of the Obama administration, the U.S. intelligence community, and the media has made him an invaluable voice on the Trump-Russia beat over the past several years. His work tends to mix damning reporting (for instance, on the shady links between the media and the underworld of spies and political operatives) with tantalizing if often unprovable speculation about who and what might be behind surface-level events.

In The Plot Against the President, Smith laid out his theory that Russiagate began as a Clinton operation to use “political operatives and dirty cops to frame her opponent” and transformed, after Trump’s victory, into an “attempted coup” by “Obama officials” to remove Trump from office. The former claim is fairly well-established, though the distinction between “dirty” and “incompetent” is often in the eye of the beholder. Smith’s latter claim about the “attempted coup” is more incendiary, but there is circumstantial evidence suggesting something more malicious than a bungled counterintelligence inquiry. Smith highlighted, among other things, DNI James Clapper’s role in disseminating the Steele dossier to the media, FBI Director James Comey’s machinations to lure Trump into an obstruction investigation, texts between FBI agents Peter Strzok and Lisa Page referring to President Barack Obama’s interest in their investigation, and the illegal leaking from the administration that led to Flynn’s ouster. All of which fits into a pattern: The Obama administration spied on senators, reporters, and likely on domestic opponents of the Iran deal, and its media playbook for Trump-Russia — using government leaks to push a preferred narrative that can then be spun and amplified by partisan “experts” — mirrored the “echo chamber” strategy it used to sell the Iran deal, as described by Smith’s Tablet colleague David Samuels in a 2016 New York Times Magazine profile of Obama aide Ben Rhodes.

In his new book, Smith expands on his theory to provide broader context for The Plot Against the President and to take account of more recent developments — the impeachment, the coronavirus lockdowns, and the protests sparked by the death of George Floyd. In Smith’s current version, Russiagate is only the highest-profile manifestation of a “permanent coup” by Obama and his inner circle dating back to at least the Iran deal and running through to the present day. As Smith puts it late in the book, “The deep state wasn’t the protagonist in the anti-Trump operation, it was an instrument that Barack Obama used in his ongoing effort to transform America.”

Smith’s book is wide-ranging and at times scattered. It retells much of the story of The Plot Against the President, but with long detours and modifications. He further develops his theory that Flynn was specifically targeted by the Obama administration because Flynn, as a former director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, was one of the few members of the incoming Trump team who understood the intelligence bureaucracy well enough to uncover the Obama administration’s abuses. This theory is hard to prove, but it received some indirect support from Steven Schrage’s recent revelation that he told FBI informant Stefan Halper before the election that taking out Flynn would be like “beheading” the Trump team, and Smith writes that several unnamed former Trump National Security Council staffers told him that as early as December, Flynn was concerned that the outgoing administration was spying on the transition team.

Smith also takes a deep dive into Ukraine, in particular Joe Biden’s son Hunter’s work for the Ukrainian energy company Burisma and the role of Eric Ciaramella, a CIA analyst and the suspected “whistleblower” in the Ukraine impeachment process, as one of Joe Biden’s gofers when the vice president was Obama’s “point man” in Ukraine. The Ukraine saga is bewilderingly complex, as is Smith’s account of it, but his basic argument is that Democrats recognized Ukraine was a potential liability for Biden. To protect him, Smith alleges, they ran another information “operation” along the same lines as Russiagate to paint the evidence of Biden’s (and, Smith suggests, Ciaramella’s) alleged corruption as part of a Trump plot to “extort” Ukraine. It’s an interesting theory of the impeachment, but Smith doesn’t provide any smoking gun to support the idea that Ciaramella was covering up for himself or that the Democrats were acting with anything like the degree of foresight and premeditation that he attributes to them. The more convincing claim is that Russiagate provided a toolkit — using coordinated leaks from the national security state to create a media circus that would provoke a political crisis — that was ready at hand once the Mueller investigation failed to provide an impeachable offense.

Finally, in a late chapter, Smith speculates that the coronavirus shutdowns and the ensuing racial justice protests have been part of a deliberate plot to demoralize Trump’s base and energize his opposition — all so that Obama, through his former vice president, can retake control of the country and “complete the transformative work he did not have time to finish in his first two terms in office.” This theory, which is Smith’s most explosive, is also his least supported — it is largely the result of inference from a handful of Obama tweets and from the fact that the former president has remained in Washington, where he has kept an office for his former aide Valerie Jarrett. In The Plot Against the President, Smith quoted a journalist who described Fusion GPS co-founder Glenn Simpson as “the typical kind of investigative reporter who needs to be reined in from time to time to keep him from wandering into conspiracy theory territory.” The same could at times be said of Smith.

But one doesn’t have to buy every particular of Smith’s theories to recognize that he has put his finger on something disturbing. To understand what that is, it’s helpful to think of Russiagate not as a discrete event but as a political technology, a method of abusing, sometimes legally and sometimes not, the American state’s awesome powers of surveillance to manipulate the media into smearing one’s opponents and constraining their actions. Consider the Russian bounty story, in which anonymous officials leaked suspect intelligence to a credulous New York Times in order to frame Trump as an agent of Putin so that they could block his planned withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan — a withdrawal supported by three-quarters of the electorate.

The Russiagate toolkit, in this understanding, is a form of information warfare, an ironic weaponization of the truism that we live in a “post-truth” environment. Critics of the president worry that the internet has broken the media’s role as informational gatekeeper, allowing any crank or Russian troll to broadcast falsehoods as if they were facts. Taken in its entirety, Smith’s work gives us a glimpse of something far more worrisome: the way in which the institutions that we formerly relied on to be arbiters of the truth have become the instruments for shadowy forces, spies and government officials, to push their narratives and pursue their interests. A wilderness of mirrors indeed.

Park MacDougald is Life and Arts editor of the Washington Examiner Magazine.