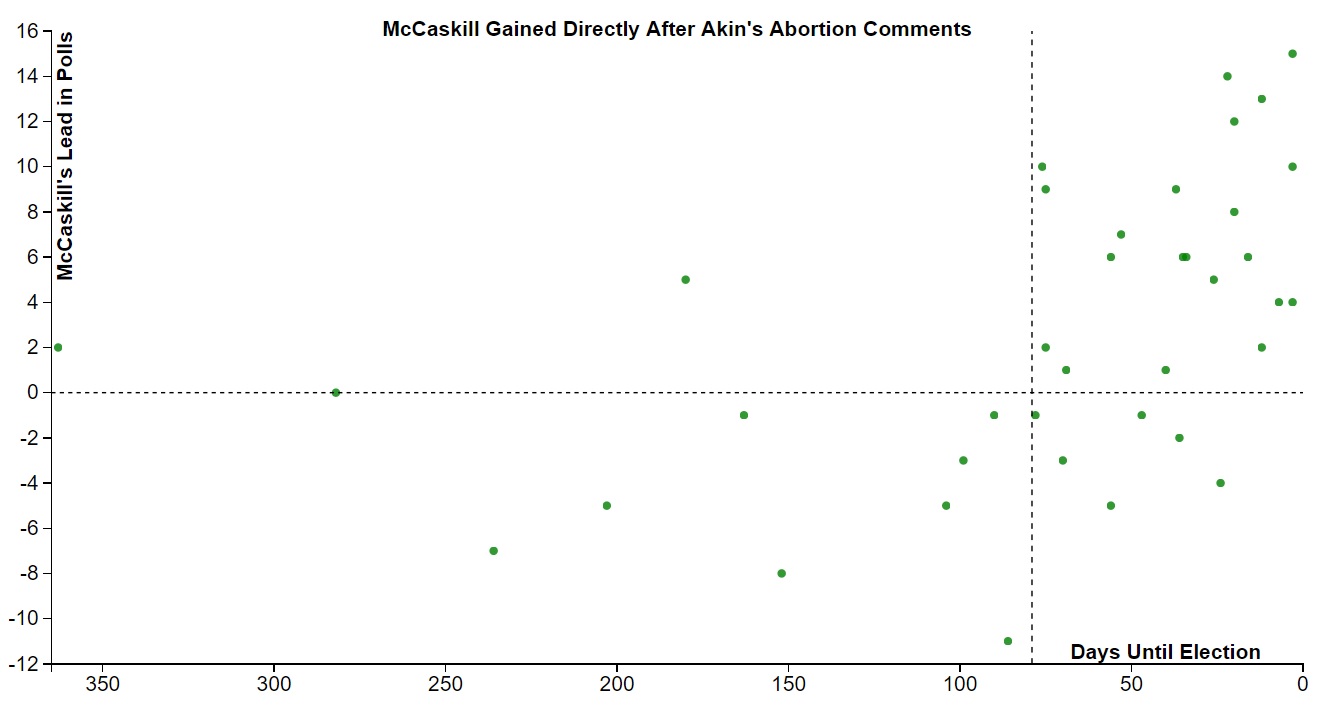

On Aug. 19, 2012, Democratic Sen. Claire McCaskill received one of the biggest gifts of her political career. While discussing abortion in the case of rape, her Republican opponent Todd Akin said, “If it’s a legitimate rape, the female body has ways to try to shut the whole thing down.” Almost immediately, Akin’s standing in the polls began to deteriorate, McCaskill’s position improved

, and in November she won re-election to the Senate by a double-digit margin.

McCaskill has a long political career that includes multiple statewide wins—such as her successful attempt to unseat incumbent Republican Sen. Jim Talent in 2006. But prior to Akin’s comments, she trailed in the polls. So it’s worth asking: Would McCaskill have won in 2012 if she had drawn a different opponent? Put differently, is Claire McCaskill the sort of politician who can win a state as red as Missouri when facing a more generic Republican?

That might seem like the sort of pointless question that elections nerds obsess over, but it’s actually an important part of gauging whether or not the Democrats will take back the Senate in 2018. If the results of the 2006 and 2012 elections indicate that McCaskill performs about as well as a generic Democrat, Republicans have a greater chance of taking the seat. But if her numbers are significantly better than what a generic Democrat would get in those situations, she’ll have an easier road to re-election.

Part of McCaskill’s success is being at the right place at the right time

Claire McCaskill’s political career can’t be boiled down to luck alone. She served in the state legislature in the 1980s, held various county-level positions, became state auditor in 1998, was re-elected in 2002 and then won the Democratic gubernatorial nomination for Missouri in 2004 (she lost that election by three points). Anyone who wins that many elections likely has significant political talent.

But she’s also often been at the right place at the right time—especially in recent Senate elections.

McCaskill won her first Senate term partially by riding the 2006 Democratic wave. Missouri wasn’t quite as red then as it is now. In 2004, George W. Bush won Missouri by seven points while winning the national popular vote by two points. And in 2000, Bush won the state by three points while narrowly losing the popular vote. In a roughly even national environment, an incumbent Republican senator in a light red state like Missouri would start with a real edge—presidential-level partisanship matters in Senate contests, and incumbents often get a boost of roughly three points compared to non-incumbents.

But 2006 was a wave election. President Bush’s approval rating was low, and Democrats won the House popular vote by eight points while unseating six incumbent Republican senators. This wave would have made any election between a Republican incumbent and a generic Democrat in Missouri a tossup. A simple regression model that uses presidential approval in each state, incumbency, and candidate quality to predict the result of the race got within one point of the final two-party vote share. The math to English translation: McCaskill’s performance in 2006 didn’t differ much from what we would have expected from a generic Democratic candidate.

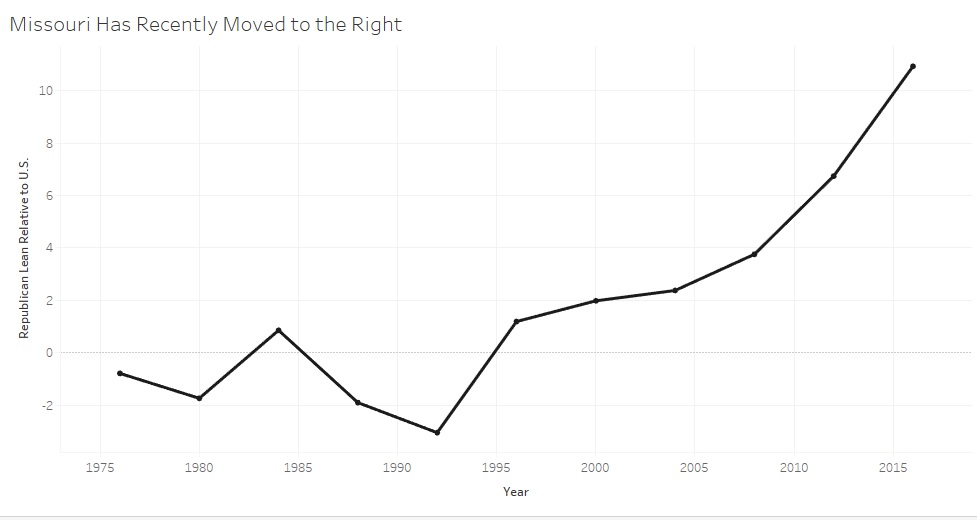

After 2006, Missouri underwent some partisan changes. The following graphic shows the difference between the two-party popular vote and the two-party presidential vote in Missouri over the last few election cycles. In other words, it shows how far the state leaned to one side relative to the nation as a whole.

For much of the 1980s through the early 2000s, Missouri didn’t lean too hard toward either party on the presidential level, even if it was drifting a bit rightward in 2008. But in 2012, the state jerked to the right. Rural areas and small towns were moving strongly toward Republicans without a strong countervailing trend in the state’s large cities.

These developments led many to believe that McCaskill would face a tough re-election fight in 2012. Mitt Romney was headed for a sizable win in the state, McCaskill was dealing with problems related to paying taxes on her personal plane and incumbency, while helpful, looked as if it might not be enough to overcome the state’s partisanship.

And, according to the polling, Akin had a real advantage before his remarks about “legitimate rape”

The trend in this graphic is clear. Before Akin talked about “legitimate rape” (the vertical dotted line) he was leading McCaskill in most polls, but afterward she gained a significant lead.

I used a similar model to the one described earlier to estimate what percentage of the vote a generic Democrat would have gotten when facing a problematic Republican in Missouri in 2012. McCaskill outperformed that estimate by a couple points, but I wouldn’t make much of that difference. Models like these produce estimates, and the difference between the model estimate and actual value wasn’t beyond what we’d expect for this model. Moreover, it’s possible that the model doesn’t include some other factor (e.g. demographics and elasticity of the state, plus Akin being worse than the average “bad candidate”) that would explain her performance without reference to her political skill.

It’s impossible to know with certainty whether McCaskill would have won a race against a generic Republican in 2012. And Akin’s victory in the GOP primary wasn’t just a lucky break—McCaskill spent significant amounts of money to help Akin win the primary, correctly predicting that he would be a weak general election candidate. But the point of this analysis isn’t to perfectly rerun counterfactuals or to evaluate the effectiveness of each of McCaskill’s individual political moves. The point is to show that her 2006 and 2012 Senate election performances weren’t wildly different from what you’d expect from a generic Democrat.

That doesn’t mean McCaskill will lose—she has some significant advantages

This interpretation of McCaskill’s recent electoral history (and there are other valid interpretations) isn’t great for her. But it’d be a mistake to write her off.

Whether a candidate is lucky or good isn’t a simple binary. McCaskill caught some lucky breaks in the past, but she’s also made some skillful moves. Boosting Akin in the primary worked out better for her than she could have possibly imagined at the time. And McCaskill could build an independent brand. Her voting record, according to DW-NOMINATE, is to the right of most Democratic senators and she opposed President Obama’s veto of the Keystone XL Pipeline. Her brand doesn’t appear to be as strong as Heidi Heitkamp’s or Joe Manchin’s, but there’s still some time for her to improve it.

Large metro areas also make up a greater share of the electorate in Missouri than in some other red states where Democrats will have to compete (e.g. West Virginia, Montana, North Dakota).

But maybe most importantly, McCaskill might end up getting lucky again. President Trump’s approval rating—something she has little to no control over—is very low. If you plug the current polling into a Senate simulator I built with Sean Trende a few months ago, you’ll see that McCaskill wins the majority of simulations. In other words, if Trump is unpopular enough, he might drag her Republican opponent down, making it easier for her to win a third term.

Obviously relying too heavily on simulations like this can lead to oversimplifying complicated races. Maybe McCaskill manages to run a solid campaign and outperform these estimates. Maybe she’ll draw an effective challenger and he or she will outperform them. Maybe Trump’s approval go up or down before Election Day 2018. There’s more than one moving part in this election.

But the point is that McCaskill, in her last two Senate elections, didn’t perform much differently than a generic Democrat might have under the same conditions. Yet if Trump is sufficiently unpopular on Election Day 2018, that might be enough for her to hold her seat.