In his fine survey of the last half-millennium of Irish history, Dublin writer John Gibney makes the enormously complicated—and usually quite tragic—story of Ireland’s past understandable. A Short History of Ireland is a concise and highly readable account that starts with the Protestant Reformation and ends more or less in our own day. The book has five parts, one for each of the centuries he discusses, further divided into chapters exploring major themes. Each of the five parts closes with a section called “Where Historians Disagree,” exploring points of scholarly contention.

The first of these disputed historical questions is: “Why did the Reformation not succeed” in Ireland? At the time Gibney’s chronicle begins, the population of the island of Ireland was predominantly Gaelic-speaking and Roman Catholic. Gaelic has declined—it’s still spoken by about 40 percent of the population of the Republic of Ireland and perhaps 5 or 10 percent of the population of Northern Ireland. But Ireland today remains overwhelmingly Catholic: The Republic of Ireland is nearly 80 percent Catholic and even in Northern Ireland the Catholic and Protestant populations are roughly equal at around 40 percent each. Gibney describes several explanations historians have offered for why the reformation didn’t “take” in Ireland. He seems partial to the idea that “the resources simply were not available to fully impose the new Episcopalian state church on a diverse population that remained strongly attached to Catholicism.”

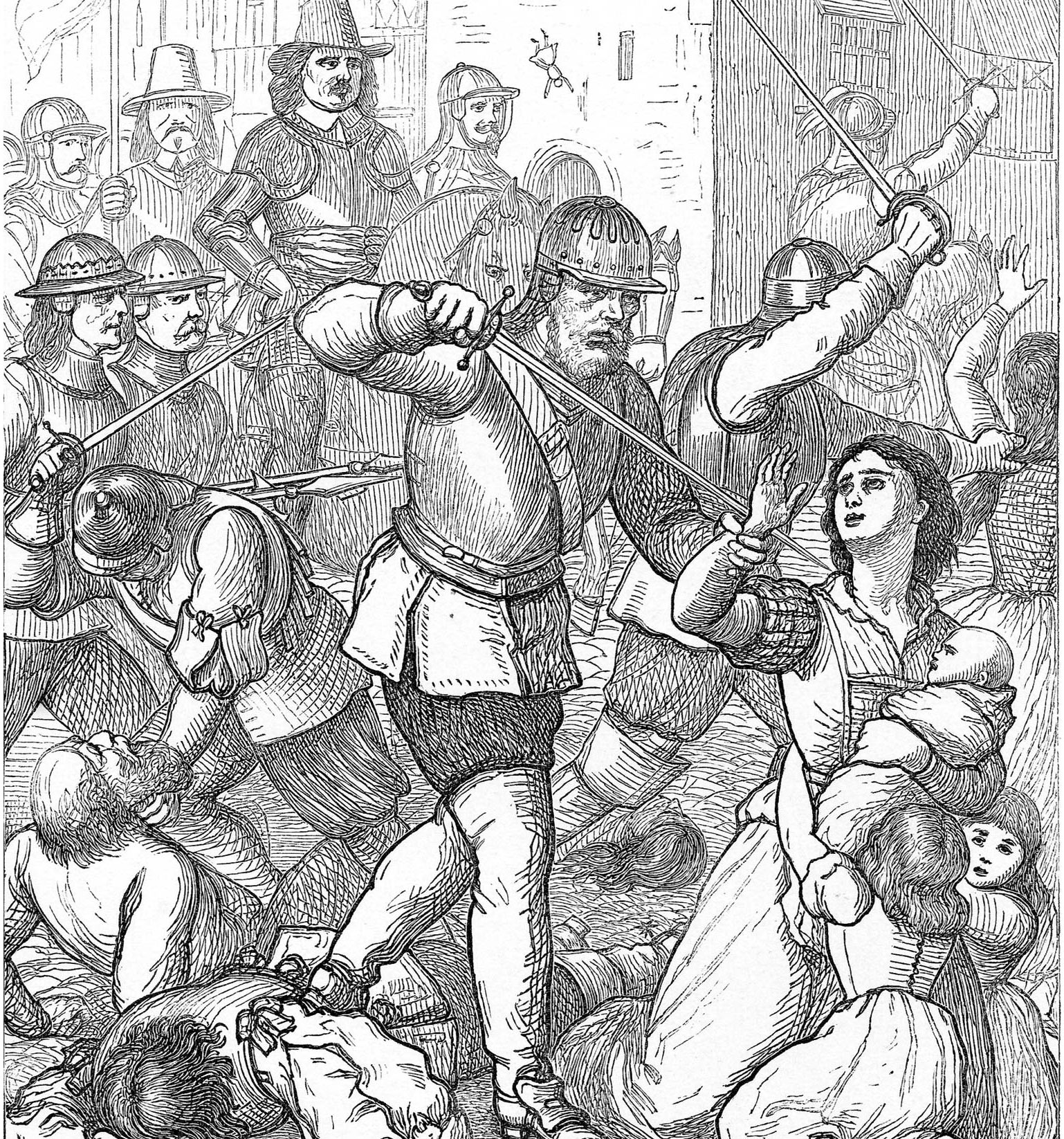

A closely related thread in Gibney’s book is the dark history of Irish-English relations, which can be traced back to the 12th century and would continue for 800 years. English maltreatment of the Irish was perhaps at its most vicious during the Cromwellian conquest and settlement (1649-1653). Gibney reports that “the overall mortality rate” inflicted on the Irish during this period is estimated by historians to “have been as high as 15-20 percent.” In addition, after the bloodshed, between 15,000 and 25,000 native Irish were sent as indentured servants to the British West Indies. (Churchill, in his History of the English-Speaking Peoples, severely reprimanded Cromwell’s “savage crimes” and “merciless wickedness,” which, he wrote, “debased the standards of human conduct and sensibly darkened the journey of mankind.”)

Following the Glorious Revolution in England, James II and his Jacobite (mostly Catholic) supporters tried to use Ireland as a center of power; they were beaten down by William of Orange and the (mostly Protestant) Williamites. The Treaty of Limerick in 1691 that ended the Jacobite conflict in Ireland was followed by the flight of the “wild geese”—the exiling from Ireland of 10,000 Irish Jacobite troops, many of whom went into French service, along with 4,000 women and children. King William’s victory confirmed the domination of Irish society by wealthy English Protestants and marked the demise of the old Gaelic aristocratic culture. An Irish poet lamented it as An longbhriseadh, the shipwreck.

Ireland would see another major uprising in 1798 during the French Revolution and sporadic uprisings thereafter—but the sadness of Ireland’s sojourn through time was not restricted to war. Belgium in 1845 saw a strange blight on potatoes; a year later, the fungus would appear with devastating consequences in Ireland, where the most impoverished were almost wholly dependent upon the potato crop. Frederick Douglass, the American former slave, visited Ireland in 1845 before the famine was at its height, as Gibney recounts:

The Irish population, Gibney notes, “went from 8.2 million in 1841 to 6.5 million in 1851. . . . A death toll of one million people from malnutrition, starvation and disease is hardly unrealistic,” with emigration accounting for the rest of the drop in population.

In the late 19th century, some Irish leaders began to push for freedom from English rule through constitutional means. Charles Stewart Parnell, an elected member of Parliament from Ireland, sought Home Rule and Irish ownership of land through peaceful petition and protest. “The first victim of the new tactic bequeathed his surname to the English language: the Mayo land agent Charles Cunningham Boycott.”

Home Rule never came. In 1912, when it looked imminent, Protestant Ulster—26 percent of Ireland’s population—rebelled. “Alongside the concerns for their livelihoods were very real fears that the Protestant minority would be victimized by the Catholic majority, for, to paraphrase one of the most famous slogans of this era, Home Rule was deemed to be Rome rule.” The Protestants created an army to resist Home Rule; in 1916, Dublin and the Catholic south responded with a rebellion, the Easter Rising, aimed at creating an Irish republic. By the early 1920s, the island was politically divided, with the northern quarter remaining in the United Kingdom. The new Irish Free State stayed in the British Commonwealth until 1949, when it officially became a republic.

Gibney’s closing sections discuss the Troubles—the years of low-level insurgency and counterinsurgency fought over whether Northern Ireland would be pried away from the United Kingdom and politically joined with the rest of the island—and their resolution in the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, as well as the economic boom of the 1990s and early 2000s that gave rise to the term “Celtic Tiger.” Today the Republic of Ireland is fully immersed in the European community. After centuries of fighting for its sovereignty, the republic in 2002 mothballed its lovely currency, the Irish pound that Yeats took the lead in designing, and exchanged it for the drab euro.

The collapse of Ireland’s economic boom in 2008 and the country’s subsequent bankruptcy ended its “existence as a sovereign and independent nation,” writes Declan Kiberd in his ominously titled After Ireland. Kiberd is an academic, based both in Ireland and the United States, and a scholar of the Irish language; his new book is part of a trilogy on Irish literature that began with Inventing Ireland (1995) and continued with Irish Classics (2000). In this third volume, which traces the work of some 30 Irish writers and poets from Samuel Beckett through today, Kiberd has plenty to say about the present moment in Irish political and cultural life.

He offers a postmortem for lost Irish identity, bemoaning the heedless consumerism of contemporary Ireland. Kiberd is uncomfortable with a 2000 Sunday Times headline proclaiming, “Money is the new Irish religion.” While the “old religion”—Roman Catholicism—was “hierarchical and repressive,” it provided “some of the social glue which held communities together.” Professor Kiberd, who now teaches at Notre Dame, invests his faith in “a strange kind of hope” that a vision of “renewed community” might be found in the work of the Irish writers he treats in this volume.

One is reminded of T. S. Eliot’s line at the end of The Waste Land, “These fragments I have shored against my ruins.” Both Eliot and Yeats recognized a spiritual dimension to reality and the impoverishment of the modern world that denies it. Because Kiberd’s approach to religion discounts spiritual longings and metaphysical meaning, looking at religion only for its social effects, he seems not to see that the disease afflicting Ireland is the same one afflicting Western Europe.

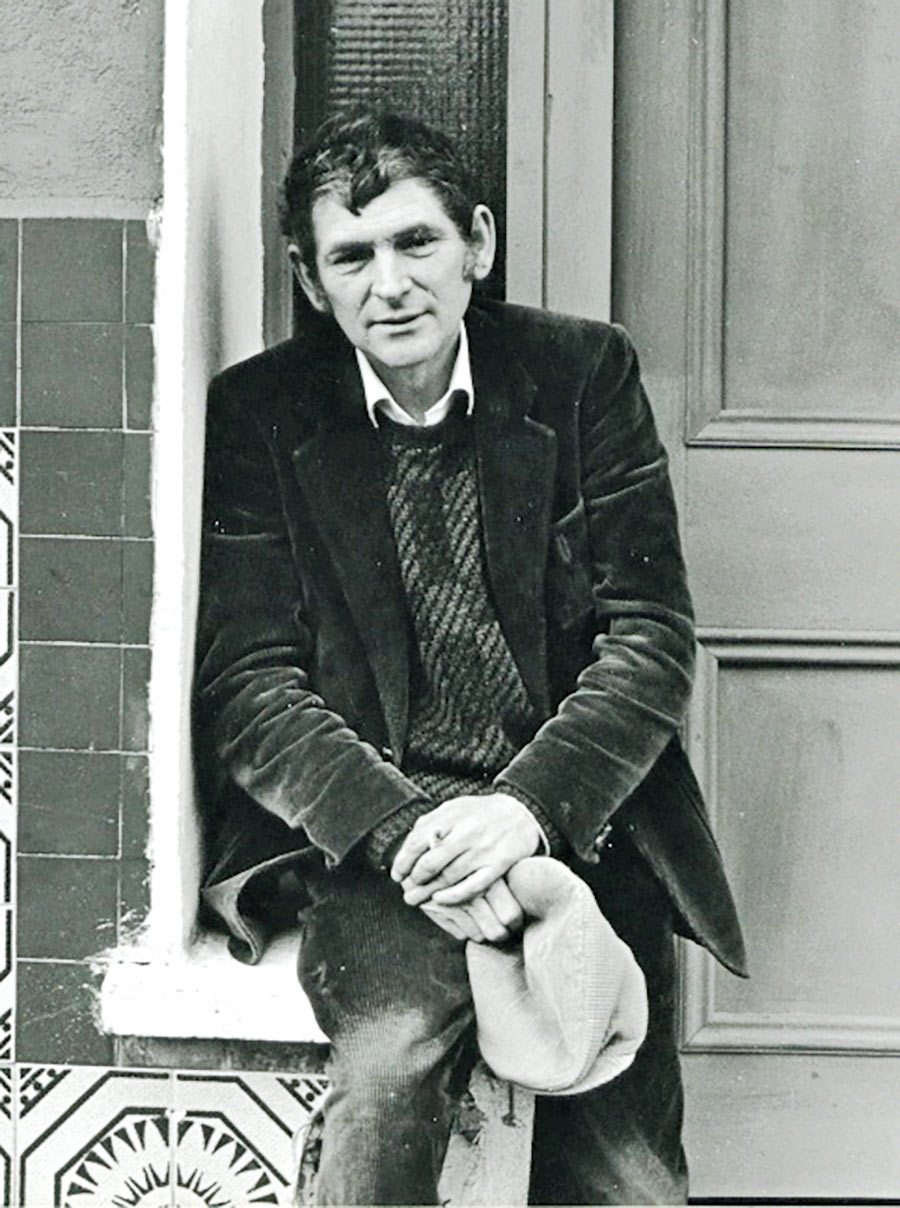

Kiberd is a fan of the literary modernism of Joyce and Beckett, yet his best essays and insights are on those Irish writers who feel themselves to be in a linguistic parenthesis between Irish and English. His essays on poets Máire Mhac an tSaoi, Eavan Boland, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, and Michael Hartnett are exemplary. In his discussion of Hartnett (1941-1999), for example, Kiberd lays out how his decision to stop writing poetry in English—“the perfect language to sell pigs in”—and to write exclusively in Irish was tied to his broader political views and was complicated by the fact that his wife was English. This in turn leads Kiberd to an intriguing discussion of the job of the poet. “Every poet senses that all official languages are already dead languages,” he writes. “All poets are—because they must be—translators.”

Kiberd extols some undeserving writers, like Edna O’Brien (born 1930), who is more an ephemeral journalist than a serious literary figure. And he gives short shrift to some writers of genius, like the brilliant poet and critic Patrick Kavanagh (1904-1967), unequivocally the greatest Irish poet after Yeats. “The purpose of art,” Kavanagh suggested in 1944, “is to project man imaginatively into the Other World, to discover in clay symbols the divine pattern.” He knew that the poet works at an anomalous crossroads where time, place, and eternity somehow meet.

Ireland today finds herself at a critical juncture. At the end of this month, Irish voters will decide on a bill to legalize abortion in the republic. It is a vote that if approved will further subsume Ireland’s spiritual heritage.

Yeats, though not a professing Christian, had hoped Ireland would resist what he called the “filthy modern tide” and retain her spiritual and cultural identity in the modern world, serving as a beacon to a decadent Europe overrun by materialism. His last instructions were—

Sing whatever is well made,

Scorn the sort now growing up

All out of shape from toe to top,

Their unremembering hearts and heads

Base-born products of base beds.

Sing the peasantry, and then

Hard-riding country gentlemen,

The holiness of monks, and after

Porter-drinkers’ randy laughter;

Sing the lords and ladies gay

That were beaten into the clay

Through seven heroic centuries;

Cast your mind on other days

That we in coming days may be

Still the indomitable Irishry.

May indomitable Irish hearts and heads heed these words.