While presidential candidates spend much of their time debating, interviewing and positioning themselves on the issues, Casey Dinges thinks their silence on one topic is deafening.

“With or without the media, our nation’s candidates need to address the serious transportation infrastructure issues we have in this country,” Dinges, senior managing director of the American Society of Civil Engineers, told the Washington Examiner. “And I think they would, if the American people understood the economic impact that a failure to act will have on their own household budgets.”

According to a recent report from the Economic Development Research Group, the numbers are staggering: If the United States doesn’t aggressively invest now in its surface infrastructure — roads, bridges, transit — by 2020:

- The country would lose a projected 877,000 jobs and 234,000 more if people don’t take pay cuts.

- American families would earn an average of $700 less a year and spend $360 more on transportation repairs.

- We’ll spend triple the amount of time in traffic.

- Businesses will spend $430 billion more for transportation and productivity would go down, causing businesses to underperform by $240 billion.

- Exports would drop, costing the country $28 billion, and the gross domestic product would be $897 billion less than expected.

Fixing our ground transportation problems sounds like a no-brainer, except it isn’t. Here Dinges explains why he believes our nation’s infrastructure issues need to move up the priority list, and soon.

“The public cares. People use these systems every day, and traffic congestion is a huge preoccupation for most of them. But it’s not enough.” (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty images)

Washington Examiner: People hate sitting in traffic and driving into potholes, so why is spending money on our transportation systems a tough sell?

Dinges: The public cares. People use these systems every day, and traffic congestion is a huge preoccupation for most of them. But it’s not enough. They aren’t motivated enough yet to tell their policymakers, “You have to go deal with that.”

Examiner: How does House Speaker John Boehner’s upcoming resignation impact the insolvent Highway Trust Fund, which is facing a deadline extension by Oct. 29?

Dinges: Speaker Boehner is in office until Oct. 30, so he has a chance to move on this. We’d like to see a long-term surface transportation bill passed instead of another extension. In July, the Senate passed a bill that includes six years of policy reforms and three years of funding to improve roads, bridges and transit systems. It was a bipartisan vote passed by 65 senators, so that’s a serious legislative marker to put out there. It’s not often that a big bill like this comes up that has support from the Chamber of Commerce to the AFL-CIO, as well as governors and mayors. Bills like this usually get attention when there is such a big bipartisan coalition.

Examiner: You’re in a room with policymakers who can do something about the challenges facing our national transportation infrastructure. What do you tell them?

Dinges: We need a multiyear commitment to spending, not another extension. We need about $106 billion per year to improve the situation, which is almost double what we’re doing now.

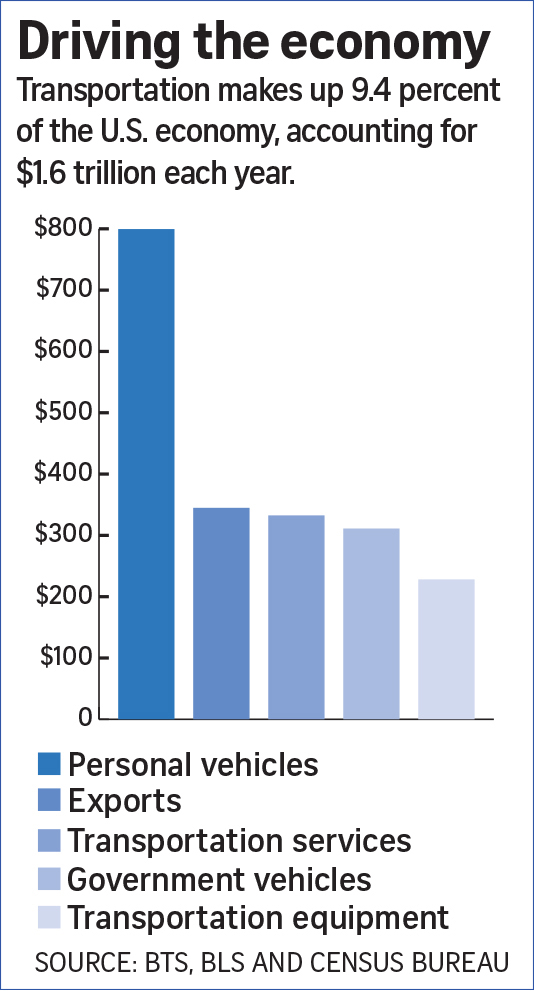

That sounds like a lot, but the U.S. economy is in the trillions, and this infrastructure is what moves goods and people every day. It should be important.

“Our bridges are at a C+. We’ve got 600,000 bridges in this country, and 66,000 of them have evident signs of deficiency and wear.” (AP Photo/Brandon Wade)

The American Society of Civil Engineers issues a report card every two years on our nation’s transportation infrastructure, and we got a “D” on the last one for surface transportation. I guess some could argue that’s up a little from the “D-” we got the time before, but it’s far from the solid “B” or better where we should be.

Our bridges are at a “C+.” We’ve got 600,000 bridges in this country, and 66,000 of them have evident signs of deficiency and wear.

I would also emphasize that when states improve their surface infrastructure, not only are private-sector companies and employees put to work, but also, new businesses are attracted and relocate to the area. Businesses want to be where they can get on the highway quickly, get to ports quickly and export quickly.

Examiner: States like Pennsylvania, Wyoming, Tennessee and others are funding their own infrastructure projects. Should these be paid for by the Highway Trust Fund?

Dinges: They might be moving on some projects that could have gotten some financing if the states had waited for Washington to move. But if Washington backs out, the states are left holding the bag. The federal government needs to act like a partner. We’re the United States of America, not the 50 states of America.

“[I]f Washington backs out [of local highway projects], the states are left holding the bag. The federal government needs to act like a partner. We’re the United States of America, not the 50 states of America.” (Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty images)

States need a multiyear commitment from the federal government that they can plan and build on. We’ve had 33 extensions to the Map-21 Transportation Bill. It’s hard for states to commit to large capital investments without a stable, long-term commitment from the government so that they know their projects will be sufficiently funded.

Examiner: What are some infrastructure opportunities not related to the trust fund?

Dinges: Some engineering innovations have strong potential to make a difference, like the Rapid Bridge Replacement project in Pennsylvania. The state created an $899 million public-private partnership in which a private company has a three-year deadline to repair 558 bridges, and then the private company has a 25-year contract to oversee them and keep them in good condition.

Public money pays for it, but the project is getting a much faster turnaround because of the private company involvement.

In Georgia, they have invested in an automated robot that can help with preemptive maintenance and quickly detect where repairs are needed. And in Texas, where they are experiencing rapid growth, the private sector fronts money to build and expand the roads, and then they get to collect the tolls for the next several decades.

Examiner: So is more private-company involvement in infrastructure projects the answer?

Dinges: It’s not the whole solution, but it is a faster turnaround than the traditional agency model. It’s one piece of the mosaic, one tool in the toolbox, but it’s not a substitute for the models we’ve been using.

Examiner: What does the average American voter not understand about our infrastructure issues?

Dinges: There have been some innovations in materials, like new generations of porous pavement allow water to permeate through the surface instead of running off into our stormwater system, as well as rubberized asphalt in the roads. It’s important for the public to understand and support these investments. When we’re talking about so much money, people want modernization and upgrades, not just repairs.

People are so busy and overwhelmed. They know roads are important to their lives, but they need time to get emotionally connected to this issue. Even in this digital world where people buy things online, they understand that the product is going to reach them by plane or truck.

But the infrastructure issues are too much for them to think about. The numbers are so huge that people’s eyes glaze over. They don’t want to get into the nitty gritty. They want their policymakers to figure it out.

Examiner: Dr. Mark Rosekind, the [National Highway Traffic Safety Administration] administrator, spoke at the Automotive Industry Action Group’s Quality Summit on Sept. 22 about NHTSA’s commitment to advancing automated vehicle technology, and of course, with that will come the need for infrastructure changes. How will the inevitable arrival of automated vehicles impact the infrastructure?

Dinges: Unless they’re going to be flying around, these automated vehicles are still going to be on the roads. Automated vehicles could lead to a more efficient use of the existing infrastructure because these driverless technologies can move people simultaneously while keeping them a safe driving distance from each other. Our population in America is about 315 million people, and we grow about 1 percent a year. That’s 70 million people in 30 years. Automated vehicles have the potential to increase our efficiency on roads that will be much more congested.

“There are 2 million miles of total paved roads in this country, but we’ve got 160,000 miles of it handling 40 percent of the traffic, 60 percent of the heavy trucking and 80 percent of tourism.” (AP Photo/Susan Montoya Bryan)

Examiner: What role can policy play in infrastructure challenges?

Dinges: High Occupancy Toll lanes, or HOT lanes, are being used for vehicles with three or more people in a car, giving them access to special high-speed lanes for free. Also, variable pricing allows drivers to pay a premium to use special toll lanes that are moving at 50-60 mph. A digital sign tells the driver the expected wait time in high-traffic areas and gives them the option of paying a fee to move into the special lane and get to their destination faster. The driver sets up an account with the state [transportation department] and a transponder in their car records when they move into the high-speed lane via an electronic toll booth.

And we need to be sure that hybrids and electrics are paying their fair share. The gas tax served us well in the past, but in the future, more cars will not be powered with gas. There is a pilot program in Oregon where people are charged for how many miles they actually travel, regardless of how the vehicle is fueled. Transponders determine how many miles a year the car was driven.

There’s a level of angst that Big Brother is watching where we go, but if there’s a fairer way, I want to hear about it.

Also, more companies could be encouraged to support telecommuting, allowing some people to work from home one to three days per week. And we could implement a nation-wide flexible workweek, where some people work from 7 a.m.-3 p.m. and others work the traditional 9 a.m.-5 p.m. That would help significantly with the rush hours.

The solutions aren’t all just about building and steel.

“There have been some innovations in materials, like new generations of porous pavement allow water to permeate through the surface instead of running off into our stormwater system, as well as rubberized asphalt in the roads. It’s important for the public to understand and support these investments.” (Photo by William Thomas Cain/Getty images)

Examiner: Are you saying that government needs to get involved in setting policy that will guarantee workers these opportunities?

Dinges: I’m not sure how heavy-handed government wants to be in this. I think companies will figure it out. But if there was policy that supports telecommuting, for example, the government could encourage companies by giving some sort of tax incentives perhaps. The role of government is probably to jawbone it by telling companies that they are part of the community and they need to consider what can be done.

That being said, we can’t pretend at the federal level that the 1993 gas tax, that’s not adjusted for inflation, is enough for the infrastructure to live off of. There are 2 million miles of total paved roads in this country, but we’ve got 160,000 miles of it handling 40 percent of the traffic, 60 percent of the heavy trucking and 80 percent of tourism. That’s four percent of our roads handling 40-80 percent of the traffic. These roads are critical for connecting our country together, so we do need some sort of federal involvement.

Examiner: You said that the presidential candidates need to be talking more about this. Where should the transportation infrastructure rank among other hot-button issues?

Dinges: The candidates could really differentiate themselves by talking about this issue. Bernie Sanders introduced a huge infrastructure initiative in the Senate this spring, and Donald Trump recently said he supports a $3.6 trillion investment in our infrastructure by 2020. Immigration, ISIS, Iran … Infrastructure is an “I” word, too.

This article appears in the Oct. 5 edition of the Washington Examiner magazine.