Despite the numerous signs that the economy is closer to a boom than to a bust, the Federal Reserve is right where it was during the darkest days of the financial crisis in December 2008: holding interest rates at zero.

Businesses have been on a job-creating hot streak, adding 3.2 million jobs over 67 straight weeks. At 5.1 percent in September, the unemployment rate is below the White House’s forecast for next year. Auto sales are booming. Foreclosures have fallen, and home prices are approaching the heights they reached before the housing bubble burst.

Yet the Fed’s interest rate target hasn’t moved from where it was when unemployment reached 10 percent.

If all goes to plan, that will change later this year, when the central bank is likely to feel comfortable enough in the recovery to begin raising its interest rate target.

Related Story: http://www.washingtonexaminer.com/article/2574118/

In that scenario laid out by Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen, the Fed gradually will begin tightening monetary policy as the U.S. reaches full employment. Then, as underemployed people are put back to work and spend more, inflation will rise to the Fed’s 2 percent target, and the central bank will have fulfilled its two congressional mandates.

But there is another scenario, a darker one that Yellen sketched out in late September at a high-profile speech at the University of Massachusetts.

She warned that the U.S. could suffer the same problems that Japan did throughout the late 1990s and 2000s. Then, Japan fell into what is now known as the “Lost Decade,” which featured slow growth, deflation and high debt. The Bank of Japan tried several times to raise interest rates, only to see growth stall.

In Janet Yellen’s model of the economy, there is no reason the United States shouldn’t get back to its full strength. (AP Photo)

The parallels between the Japanese experience and what the U.S. is undergoing today are deep and many. Japan’s lingering monetary problems are only now being fully reckoned with by a newly empowered nationalistic right-wing president set on reversing economic stagnation and rebuilding Japanese power.

In Yellen’s model of the economy, which is the mainstream view among academics and central bankers, the U.S. shouldn’t be like Japan and the economy should get back to full strength.

But she has acknowledged, as the Fed has debated raising rates, that modern economics doesn’t have all the answers. Events could unfold just the way the Fed hopes they won’t, leading to stagnation, more monetary stimulus and growing political unease over the central bank’s policies.

The inflation question

Yellen’s core assumption is that there is a link between unemployment and inflation: In an economy operating below full strength, a falling unemployment rate should lead to higher inflation.

Her view is different than the economic beliefs that led to the “stagflation” of the 1960s and 1970s, which saw high unemployment with soaring inflation. After the experience of stagflation and the academic efforts of the famed libertarian University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman, among others, it became widely accepted that the Fed could not trade higher inflation for lower unemployment.

Yellen and today’s Fed don’t assume that they can tinker with inflation to move unemployment.

Instead, as Yellen emphasized at her speech at UMass, she believes that monetary easing can lower unemployment under the critical conditions that inflation is low and inflation expectations are stable.

As long as investors and normal people think that inflation will remain steady, inflation is not likely to spiral out of control. In Yellen’s view, stable inflation expectations mean that, with low unemployment, easy money will accelerate jobs growth and raise inflation without sending prices spiraling.

“I expect that inflation will return to 2 percent over the next few years as the temporary factors that are currently weighing on inflation wane,” Yellen said in her UMass speech, “provided that economic growth continues to be strong enough to complete the return to maximum employment and long-run inflation expectations remain well-anchored.”

In plain English, what Yellen meant is that everything is going according to plan.

Yes, the situation is worse for workers than the low unemployment rate suggests, especially for people forced into part-time work or who have become so discouraged they have dropped the job hunt entirely.

The U.S. should be on guard for the possibility that slower growth and lower interest rates might be the future, as the retirement of the Baby Boom generation has begun. (AP Photo)

True, growth has been slow and fitful. Recently, drillers have been slammed by the drop in oil prices and manufacturers have seen their exports crimped by the rise of the dollar, both of which can be traced to slowing growth in China and elsewhere overseas.

And inflation has been closer to zero than to the Fed’s 2 percent target in recent months, after being below target for more than three years.

Add up those factors, and there is a case to be made that the U.S. economy needs easier money, not tighter money. Some members of the Fed, such as Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis President Narayana Kocherlakota, have voiced that argument in advance of the Fed’s widely anticipated meetings at the end of October and in December.

But not in Yellen’s view. With employment growing and inflation expectations stable, she expects the effects of falling oil prices and a strengthening dollar to be temporary and for inflation to rise.

In her outlook, the Fed can’t afford to wait too long to begin raising rates, because monetary policy hits the economy on a “lag.” If they don’t act in time, central bank officials could risk the economy overheating while they’re still holding interest rates at zero with a $4.5 trillion balance sheet, a recipe for soaring inflation.

Defying expectations

Japan, however, experienced exactly what is not supposed to happen under Yellen’s model of the economy.

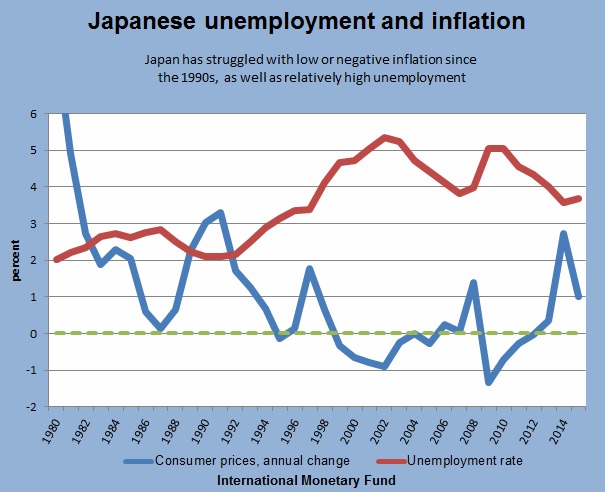

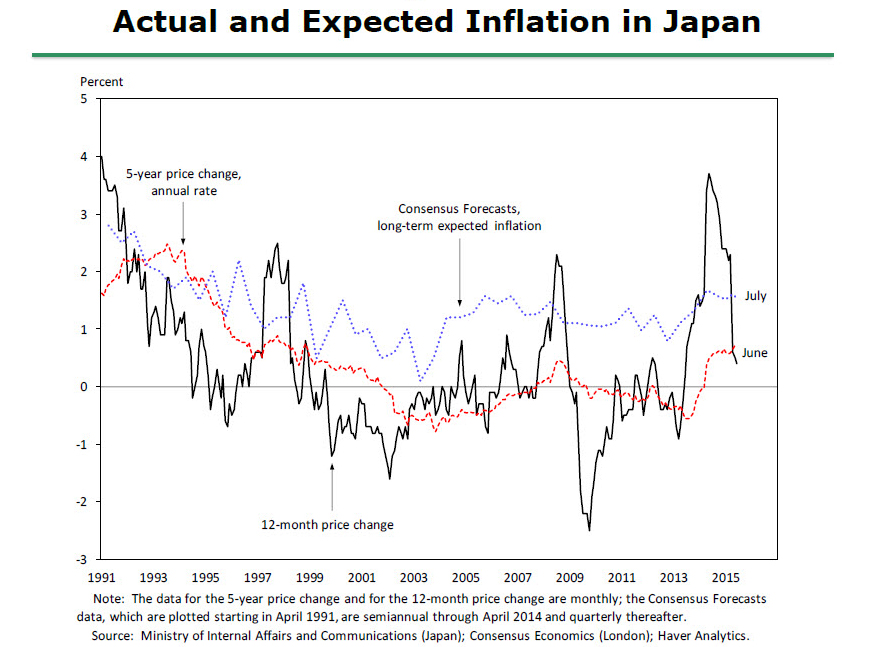

As the economy stagnated throughout the 1990s, the Bank of Japan cut interest rates to zero, promised markets low rates for longer and started quantitative easing. Yet inflation never materialized, although expectations remained anchored and unemployment never rose above 5.3 percent. That episode has some economists worried the same fate could befall the U.S., with growth and inflation never picking up even as the unemployment rate falls to pre-recession levels.

“In my view, inflation will be lower than what the Fed thinks,” said Scott Sumner, a prominent monetary policy expert.

Japan’s example “showed it’s possible to fall into deflation even when the public is expecting inflation,” said Sumner, who directs a monetary policy program at the libertarian Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

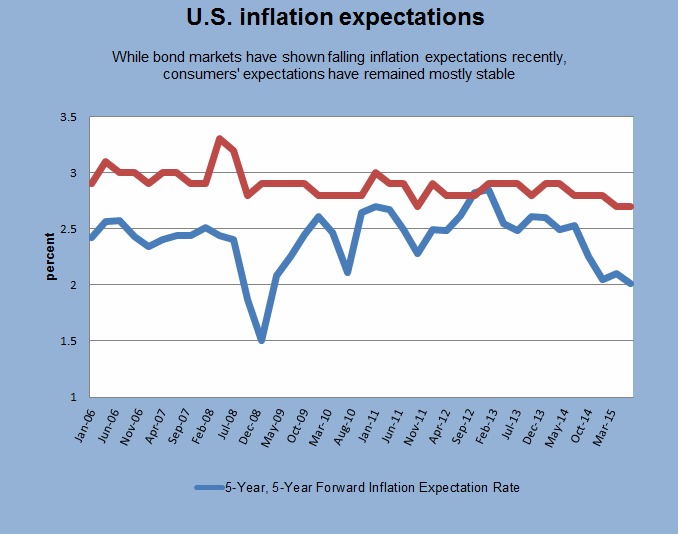

There are two ways to gauge inflation expectations. One is by looking at surveys of people, such as the University of Michigan’s survey of consumers. Those surveys show that Americans expect inflation to be stable.

The other is to look at bond markets, in particular the compensation that investors demand for taking on inflation risk in government securities.

It’s a controversy within the Fed as to what lessons can be drawn from those measures. But Sumner said bond market measures suggest that investors don’t expect inflation to rise at anywhere near the pace the Fed is anticipating.

Furthermore, bond market prices suggest that investors expect the Fed to raise rates much more slowly than Fed members themselves projected at their September meeting, a reflection that markets expect the Fed to make less progress toward its 2 percent inflation target.

Such skepticism has currency within the Fed, even if not with Yellen.

“We look back in history to the late ’90s, early 2000s, this is the kind of move they made that is now viewed as a mistake,” Kocherlakota said in September of Japan’s early attempts to tighten money based on stable inflation expectations.

Kocherlakota is a rarity in central banking: He apparently has changed his mind entirely about what ails the economy and how the Fed should respond. After being a top “hawk” early in the recovery, the former child math prodigy and academic reversed course and has become, in recent years, the Fed system’s most prominent “dove,” advocating easier money and worrying about inflation being too low.

In a CNBC interview in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, during a highly anticipated meeting of central bankers from across the world, Kocherlakota warned his colleagues not to repeat Japan’s mistakes.

“I think that right now we’re sending the message that we’re very nervous about ever exceeding our 2 percent inflation target, we’re treating it like a ceiling,” Kocherlakota said. “And that means that the credibility of getting back there is, I think, impaired.”

The Japanese experience

Japan’s labor force has been shrinking since the mid-’90s, and its population has been declining since it peaked at more than 128 million in 2009. (AP Photo)

Since the collapse of Lehman Bros. and the near-destruction of Wall Street, the Fed has looked to the Bank of Japan for as a model for how to manage deflationary forces.

The parallels run deep, starting with Japan suffering the collapse of a massive financial market bubble, including real estate, to start the 1990s. Previously, Japan had enjoyed a golden age, with its economy and incomes growing rapidly enough to scare U.S. officials into worrying about the Land of the Rising Sun overtaking the U.S.

But the economy overheated, and the Nikkei 225 stock index fell by nearly 40 percent over the first half of 1990, as the country entered a recession.

Japanese economic growth stalled throughout the ’90s and unemployment increased. The Bank of Japan responded, as central banks normally do, by cutting interest rates.

But that failed to stimulate growth or to prevent rapid disinflation and outright deflation.

Unanticipated deflation, or lower-than-expected inflation, is thought to be harmful to businesses because it hurts their balance sheets. Companies with long-term debt must pay those debts, which they took out when the currency was worth less, with currency that is now more valuable.

By the late 1990s, some top U.S. analysts had come around to the belief that below-target inflation was at the heart of Japan’s economic problems, and that the Bank of Japan was to blame for keeping monetary policy too tight.

Among those analysts was Friedman.

In a 1997 Wall Street Journal op-ed, he wrote the “surest road to a healthy economic recovery is to increase the rate of monetary growth, to shift from tight money to easier money.”

Just because the Bank of Japan had cut its target interest rate to 0.5 percent did not mean money was loose or that the central bank could do no more, Friedman noted.

Instead, he suggested, it could engage in what is now known as “quantitative easing,” or buying government bonds in large quantities with newly created money, thereby expanding the money supply.

If the Bank of Japan followed his advice, Friedman predicted, “After a year or so, the economy will expand more rapidly; output will grow, and after another delay, inflation will increase moderately.”

By 1999, the Bank of Japan had taken the first step, pushing its interest rate target all the way to zero. That December, it was urged to loosen money even more, by a Princeton professor named Ben Bernanke.

Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda has promised open-ended quantitative easing until inflation rises to its 2 percent target, but on a much larger scale. (AP Photo)

In a speech prepared for a meeting of academic economists, Bernanke noted that Japan for a long time had been suffering below-target inflation along with slow nominal gross domestic product growth — that is, the sum total of all spending in the economy. Those symptoms, he said, were “consistent with an economy in which nominal aggregate demand is growing too slowly for the patient’s health.”

Even with rates already at zero, Bernanke suggested, the Bank of Japan could do more to ease money to boost nominal spending. It could promise to hold interest rates at zero for longer, he said, engage in quantitative easing, or print money for the government to send to households — the “helicopter drop” proposal for which Bernanke would later earn the moniker “Helicopter Ben.”

Instead, the Bank of Japan went the other direction, raising rates to 0.25 percent in early 2000. After growth again deteriorated, the central bank lowered rates to 0.15 percent in early 2001 and then started a quantitative easing program.

Over the 2000s, Japan saw improved growth, enough to raise rates to 0.5 percent in 2007. Then the global financial crisis hit, denting economic output and sending inflation into negative territory again.

Lessons learned

The financial crisis in the U.S. made the lessons learned from Japan’s problems acutely relevant to the Fed.

Yellen, then the president of the San Francisco regional Fed bank, warned as early as November 2009 that the U.S. could go down the same path as Japan.

“A key factor putting a floor on the decline in the inflation rate is the public’s confidence that we will do whatever it takes to bring the economy back from recession and keep inflation from falling too low,” Yellen told the other members of the committee, according to newly released transcripts. “If we [waver] from that pledge and tighten too soon, confidence in our commitment to economic recovery and price stability could be undermined, and that could be a recipe for an extended episode of disinflation or even deflation like the one Japan suffered through.”

Warnings about Japan’s record were echoed in the early days of the recession by many of the “doves,” including the Boston Fed’s Eric Rosengren and St. Louis’ James Bullard.

Repeating Japan’s experience is a possibility that “we have long been aware of and have been taking into account,” Yellen said at a press conference this year.

Japan itself is still trying to draw the right lesson from its Lost Decade in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

After seeing the economy shrink and fall back into deflation, Shinzo Abe took office in late 2012, promising an end to deflation once and for all.

After seeing the economy shrink and fall back into deflation, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe took office in late 2012 promising an end to deflation once and for all. (AP Photo)

Abe, a member of the conservative Liberal Democratic Party, promised a three-part approach to overcome deflation and return Japan to growth. The “three arrows” of what has since been termed “Abenomics” are, essentially, monetary stimulus, fiscal stimulus and structural reforms. The last arrow includes policies to liberalize business and labor in Japan, such as the recently negotiated Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal that would reduce tariffs and elevate Japan’s status in the Pacific.

With Abe’s backing, Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda has turned the first arrow into, essentially, an unprecedented experiment in monetary policy. In a version of what the Fed did between 2012-14, the Bank of Japan has promised open-ended quantitative easing until inflation rises to its 2 percent target, but on a much larger scale. The total assets that the Bank of Japan holds are nearing three-quarters of Japan’s economic output. In comparison, the Fed’s holdings are only about a quarter of U.S. nominal GDP.

There are some early signs of inflation returning, but whether Abenomics has succeeded in reviving growth and dispelling deflation remains to be seen.

What is more clear, however, is that the long-stagnant economy provided a political opening for Abe, and he took it.

“Abe simply doesn’t want to just lay down and take it,” said Scott Seaman, a Japan analyst at the Eurasia Group, which consults on geopolitical risks. “His economic policy — strengthen the economy — is very closely connected to his really bigger goal, at least it’s kind of a personal quest of his, to strengthen Japan’s defense and security. A strong economy allows them to do a lot more to strengthen security than they otherwise could.”

Abe has boosted spending and aggressively positioned Japanese forces to counter China’s expansion near Japan. He has commissioned highly symbolic acts of right-wing nationalism, such as skirting an apology for Japan’s provision of “comfort women,” prisoners forced to be prostitutes for Japanese soldiers during World War II, during his visit to the White House in late spring. In 2013, he visited the Yasukuni Shrine, a memorial that honors World War II soldiers, some of whom were war criminals. The visit was seen as a provocation to China and Korea.

Abe’s aggressive fiscal and monetary stimulus may help him with Japanese voters not sold on his efforts to remake Japan as a military power. Similarly, his right-wing exploits help him keep nationalists in his coalition as he seeks to renew economic growth.

It’s an example of how prolonged economic malaise can create political movements and coalitions that otherwise would not be available.

And it’s one for the Fed to weigh as the U.S. stretches toward eight years of zero rates, tepid growth and low inflation.

Deeper parallels

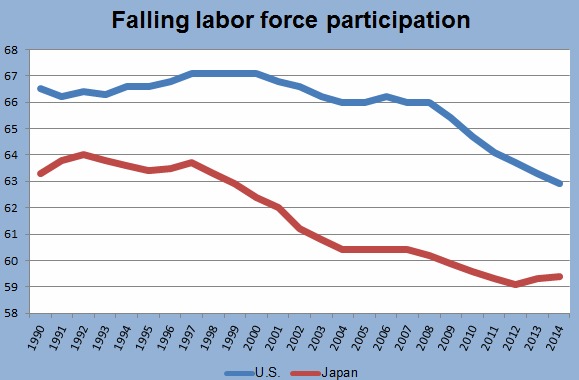

Japan and the U.S. have one more parallel that may prove to be key: A shrinking labor force.

Japan’s labor force has been shrinking since the mid-’90s, and its population has been declining since it peaked at more than 128 million in 2009.

“They are groping their way through a process that no other country in history has gone through,” Seaman said.

An aging population and shrinking labor force do two things to an economy.

The first is that they slow growth. GDP growth is a combination of labor force growth and productivity — the number of workers multiplied by the amount each worker produces. If the labor force is shrinking, growth would be expected to slow, all things being equal.

The second is that they put downward pressure on interest rates. An aging population, as Japan has, means there are more retired savers versus younger people looking to borrow for homes or college or generally to invest in the future.

In Japan, the aging of the country has been extreme. There are twice as many people over age 65 as there are children under age 15. Of major countries, it has the highest median age, at just over 46 years old.

That demographic background means that Japan’s slow growth over the past two decades has not been as calamitous as it might appear. Although better monetary policy could have prevented undue joblessness, said Joseph Gagnon, an economist at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, slower growth and lower interest rates would be expected with a rapidly aging population.

“It’s less extreme here because our population isn’t aging as rapidly as Japan’s, and we still have more immigration than Japan. So our population isn’t slowing as much as Japan’s, but it is slowing,” said Gagnon, who previously worked on international issues at the Fed’s Board of Governors.

Nevertheless, the U.S. should be on guard for the possibility that slower growth and lower interest rates might be the future, as the retirement of the Baby Boom generation has begun.

The U.S. labor force participation rate topped out at just over 66 percent before the recession. Since then, it’s dropped to 62.4 percent, the lowest level since the late 1970s.

Partly, that decline reflects that the oldest of the roughly 80 million baby boomers reached retirement age shortly after the recession. To some degree, it also marks the fact that the jobs market was so bad that millions of workers quit searching for positions.

Even as businesses recover and create more jobs, however, the U.S. workforce will continue to shrink because of demographic change. Goldman Sachs economists estimated in October that the participation rate will continue to fall by a quarter of a percentage point each year.

Yellen and other Fed members must be aware that such demographic changes could mean that markets will need lower interest rates for longer, even if other indicators such as the unemployment rate are at levels that in the past would scream for higher rates.

“Maybe the Japanese were not quick enough to see that and kept policy too tight. So I think we have to be on guard,” Gagnon said.

Where that leaves the U.S.

In the months ahead, Yellen will have to weigh the example of Japan and determine whether the similarities with the U.S. are deep enough that she risks an American Lost Decade if the Fed moves to tighten monetary policy.

For some experts, there’s no comparison.

Takatoshi Ito, a Japanese economist at Columbia University who has served as an adviser to the Japanese prime minister and in the Ministry of Finance, told the Washington Examiner that “the situations are different.”

“In Japan, inflation expectation stayed low, as the [Bank of Japan] communicated and acted as if the target was zero,” he explained. “In the U.S., the expected inflation rate is firmly anchored.”

On the other hand, Richard Koo, chief economist at the Nomura Research Institute, argued that the example of Japan discourages further easy money from the Fed.

“The central bank cannot afford to be seen as behind the curve,” he acknowledged, noting that the Fed’s swollen balance sheet could cause rampant inflation if Yellen is too slow to tighten monetary policy.

Neverthless, Koo pointed out, businesses and households are still not borrowing money, even seven years after the collapse of Lehman Bros., a situation that also held throughout Japan’s Lost Decade, and one that suggests that the economy is not ready for higher rates.

“But at the same time, we don’t have [the] U.S. private sector actually borrowing money even at zero interest rates, and so if you raise interest … they’ll borrow even less, right?” Koo said. “And so those are the issues that Janet Yellen has to struggle with.”

For now, Yellen’s faith is in stable expectations. Inflation will rise with more job growth, she predicted at her press conference in September. But she added a crucial caveat: “If our understanding of the inflationary process is correct.”