If your focus was on enjoying the holidays late last month, you may have missed a few things. The week ending on Dec. 21 brought a deluge of difficulty for the Trump administration.

First off, the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee met and raised the short-term interest rate another notch, doing so in spite of Trump’s high-decibel call for lower rates. By the end of the week, the president was inquiring as to how he might fire Fed Chairman Jerome Powell.

Then the president unexpectedly announced the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Syria and floated the possibility of doing the same in Afghanistan, without consulting his military advisers and conferring with the leadership of countries involved in joint anti-Islamic State combat. As a result, Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis submitted his resignation effective early 2019.

Finally, as if that wasn’t already enough to make for a two-Tylenol headache, the week ended with a partial government shutdown. White House and congressional leaders failed to find a way to fund Trump’s $5 billion Mexico border wall while also keeping the wheels of government turning. Santa Claus must have wondered how to fill the stockings of federal workers who were sent home or forced to work without pay during Christmas week.

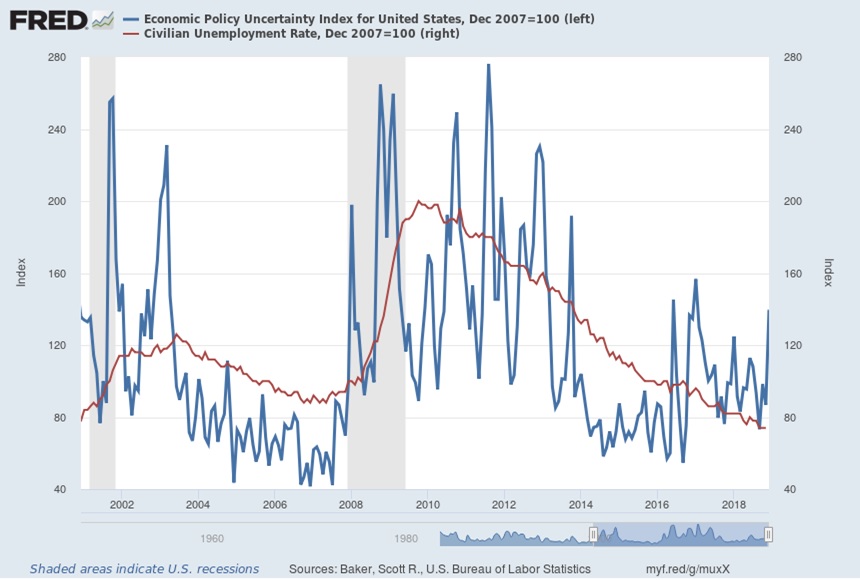

I show the association of these and earlier events derived from a daily U.S. economic policy uncertainty index in the accompanying chart. The index is based on the occurrence of certain words found in 1,000 U.S. daily papers: “uncertain,” “uncertainty,” “legislation,” “regulation,” “congress,” “Federal Reserve,” and “White House.”

Direct your attention to the Dec. 21 spike, and notice how that spike compares with the earlier Trump election and Brexit vote spikes. One can see various high points that coincide with policy crises. And, as the line tracking the U.S. unemployment rate shows, there is a troubling association between policy uncertainty and joblessness.

Why the unemployment relationship?

Consider that each of the December policy controversies upended planned activities for a huge number of affected individuals and organizations in the United States and worldwide. A government shutdown directly disturbs almost a million U.S. government workers while interrupting countless pending and highly sought actions — a passport, a patent approval, a hearing before the Federal Trade Commission, a long-awaited decision on a pending drug approval, or something as simple and wonderful as a family Yellowstone Christmas vacation that must now be canceled.

As a result, a critically important business conference may be canceled, a stock offering based on the patent may be postponed, and business expansion expectations awaiting FTC approval of a pending merger or FDA approval of a new drug may be revised downward. If nothing else, there will be a smaller crowd at the Montana hotel near Yellowstone’s west gate, and fewer people will be enjoying barbecue at a local restaurant.

Uncoordinated large-scale military reversals leave a wake of uncertainty for our allies who are engaged in costly efforts to organize troops and materiel for a continued, agreed-up struggle. Presidential challenges to the Fed’s independence, which could cause officials to (unconsciously or otherwise) take opposing action just for the sake of asserting their authority. Meanwhile, millions of financial agents worldwide watch and wait until the air clears.

As a general rule, policy uncertainty is prosperity’s enemy. The ordeal of change does not usually come cheaply. But, of course, there are exceptions to the rule. The cost of uncertainty may sometimes be less than what we pay for certainty — like, for example, costly and ineffective rules that may need to be revised.

Wise politicians and their advisers must know all this. Even so, when caught in the heat of political battles, those same politicians may forget how much cost they impose on the people they are sworn to serve when, by their actions, they cause policy uncertainty to rise to extreme levels.

Bruce Yandle is a contributor to the Washington Examiner’s Beltway Confidential blog. He is a distinguished adjunct fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and dean emeritus of the Clemson University College of Business & Behavioral Science. He developed the “Bootleggers and Baptists” political model.