President Obama’s pick to fill the vacancy on the Supreme Court has rock-solid support from all major Democratic party figures and liberal leaders, save one: presidential nominee Hillary Clinton.

She has not opposed Judge Merrick Garland, but nor has she promised to re-submit his nomination should she win the fall election. She has strongly hinted, in fact, that she would prefer to pick someone else.

“When I am president, I will take stock of where we are and move from there,” she said during an April Democratic primary debate when asked if she would re-submit his nomination.

Clinton’s ambiguity may, ironically, be the best thing for Garland’s chances. Because Obama did not choose an extreme left-liberal, Senate Republicans may come to view Garland as their least-worst option, in which case they could confirm him in a post-election lame-duck session if Clinton wins, especially if they also lose their Senate majority.

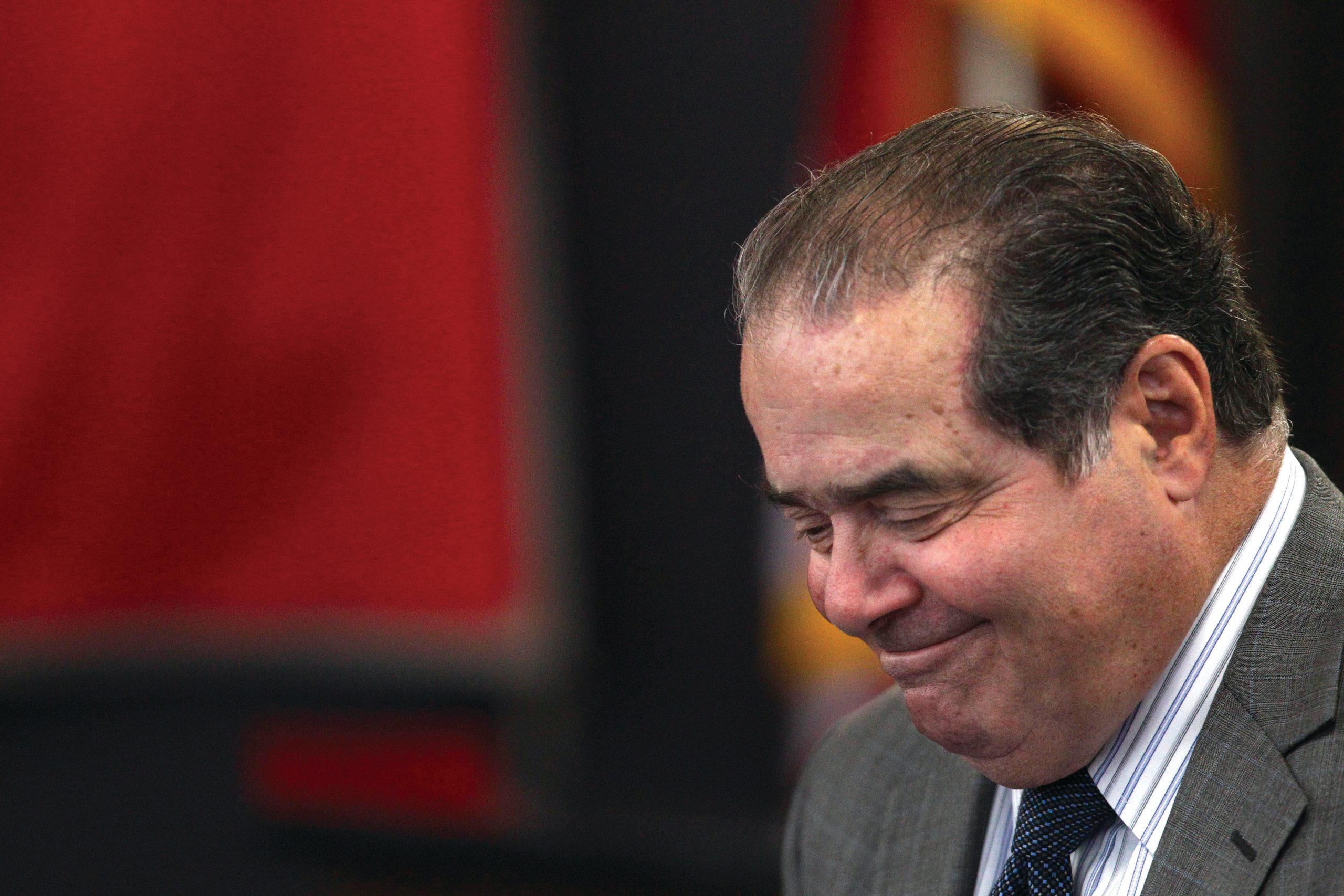

Presidential nominee Hillary Clinton could choose a hardliner to replace the late Justice Antonin Scalia. (AP Photo)

The alternative is to let Clinton choose the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s replacement, and she could pick a hardliner.

That’s what liberal activists backing Garland hope, though they concede it is a longshot. “Everything comes down to how the election plays out,” said Chris Kang, a former White House deputy counsel who ran Obama’s judicial section process.

Approving Garland as a safer option is on the minds of some Republicans. Sen. Jeff Flake, R-Ariz., told NBC in May that “if we come to a point, I have said all along, where we’re going to lose the election or we lose the election in November, then we ought to approve him quickly. I’m certain that he’ll be more conservative than a Hillary Clinton nomination, come January.”

Republican Senate staffers say, however, that is a minority view. All that really matters is how the nominee would vote on the bench. They don’t think Clinton would pick anyone different in that regard.

Hillary Clinton’s ambiguity may, ironically, be the best thing for Merrick Garland’s chances to receive the Supreme Court nomination. (AP Photo)

Privately, aides express amusement at the idea that Garland’s nomination isn’t already dead. They scoff at the idea that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., will relent and allow hearings.

“The strategy at this point is just to let the Democrats continue to talk to an empty room and run out the clock,” said a Republican Senate aide who requested anonymity.

The question is whether these attitudes will hold after the election. Garland’s nomination has, in effect, become the functional equivalent of a three-way stand-off in a spaghetti western. On one side are McConnell and the Republicans, who have to weigh their opposition to Garland against a hypothetical future administration’s alternate pick.

On another side is the Obama administration, which has to weigh the option of sticking by Garland against potentially losing the pick to the next administration.

And finally there is Clinton, who apparently wants to make her own pick but cannot risk openly opposing Garland without looking disloyal to Obama.

Clinton apparently wants to make her own Supreme Court pick but cannot risk openly opposing Merrick Garland without looking disloyal to Obama. (AP Photo)

And that is if Clinton actually wins in the fall. At press time, her lead over Donald Trump in the RealClearPolitics average of polls was narrow and shrinking. Should Donald Trump win, it’s a certainty that Garland will not be confirmed this fall or re-nominated next year.

This situation is hardly what Obama intended when he nominated Garland, chief judge of the D.C. Appeals Court and a former clerk for Justice William Brennan, on March 16 to replace Scalia, who died the month before.

The administration argued that the pick reached out to Republicans, and pointed to past praise from Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, and statements from Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, and Mark Kirk, R-Ill., that they would back him.

Republican Senate aides counter that it’s absurd that past praise means they’d rubber-stamp Garland for the Supreme Court. In any event, there was never any serious engagement between the White House and the leadership on picking a nominee, they say. Garland was presented as the only option.

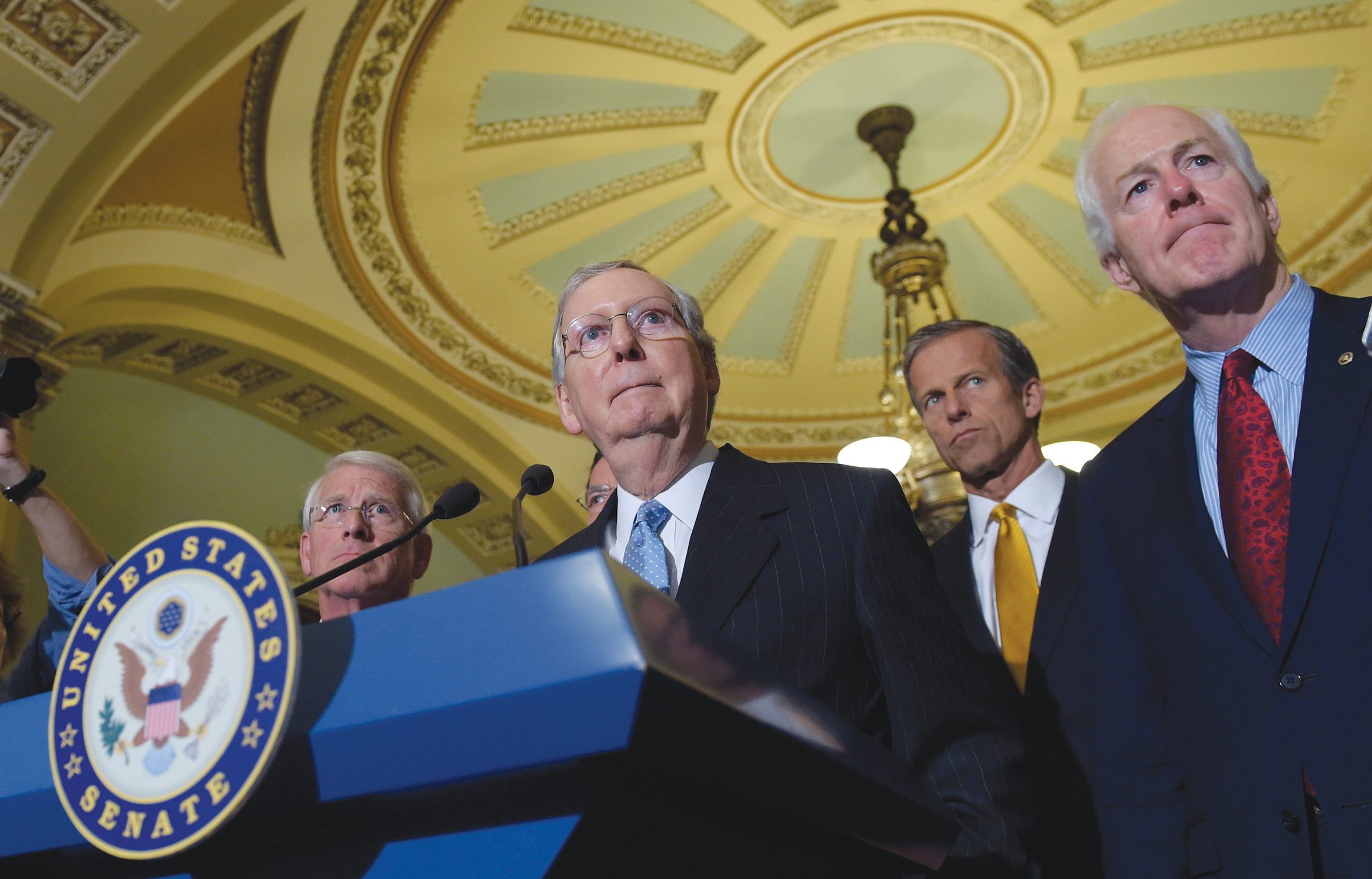

Any momentum Garland had evaporated shortly after the announcement when McConnell and other leading Republicans ruled out a vote, arguing that a Supreme Court replacement shouldn’t be made in an election year and should instead belong to the next administration. Conservative activists, who argue Garland’s record is liberal, cheered the move.

Democrats attacked it as partisan and told the GOP that it would pay a price for its obstruction. This arguement deflated after Republicans pointed out that Vice President Joe Biden blocked Republican picks in even more partisan circumstances.

In a 1992 speech on the Senate floor, Biden, then a Delaware senator and chairman of the Judiciary Committee, said that if a Supreme Court vacancy opened that year, President George H.W. Bush should refrain from nominating someone until at least after the election. (AP Photo)

In a 1992 speech on the Senate floor, Biden, then a Delaware senator and chairman of the Judiciary Committee, said that if a Supreme Court vacancy opened that year, President George H.W. Bush should refrain from nominating someone until at least after the election.

If he did, then “the Senate Judiciary Committee should seriously consider not scheduling confirmation hearings on the nomination until after the political campaign season is over.”

Biden was thus saying that even in the final year of a president’s first term — not just the second term, as is the case now — an incumbent’s pick should be prevented. McConnell made a point of saying he was following the “Biden rule.”

Kang argues that Biden’s remarks were taken out of context, since there was no Supreme Court vacancy at the time, but concedes that bringing them back up was a PR problem for Democrats.

“It had an impact in that it allowed the GOP to muddy the waters,” he said.

With most polls showing Clinton ahead of Trump, few fear that anyone other than a liberal will replace Scalia on the bench. (AP Photo)

Garland’s nomination dropped off the political radar. He wasn’t a major topic at the Democratic National Convention in July. Not even Obama mentioned him or the Supreme Court in his convention speech. Senate Democratic candidates are not using the issue in campaign ads.

The administration still pushes the issue but gets no traction. A Sept. 8 press conference with Biden and Capitol Hill Democrats illustrated the problem. The vice president warned that Republican leaders were creating an “incredibly dangerous precedent” by declining to even allow hearings on Garland. There were “real consequences” for leaving the court without a full nine members, he warned.

Recalling his own tenure as Judiciary Committee chairman, Biden boasted that he had ensured that all the presidents’ nominees, regardless of party, got to the Senate floor.

“I was pilloried by some of my friends in the Democratic Party” for doing that, he boasted, inadvertently revealing that even back then many members of his own party didn’t think a president’s nominees should have a vote, the position Republicans take now.

Democratic lawmakers standing behind the vice president, who had been nodding along to his comments, stopped when he made this comment.

Liberal activists say they haven’t given up. “Let’s be clear: There is absolutely still time to have a vote on Garland,” said Marge Baker, executive vice president for People for the American Way.

Activists point to a comment Senate Judiciary Chairman Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, made to reporters in late August. He said that if, after the election, a majority of the Senate pushed for a vote on Garland, then “I don’t feel that I could stand in the way of that.”

A Grassley spokesman subsequently said the senator was merely re-stating a position he had held from the start, noting that 52 senators are on record opposing a vote on Garland.

Otherwise, those pushing for Garland concede they don’t have much else they can point to, even counting rumors.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky. and other leading Republicans ruled out a vote, arguing that a Supreme Court replacement shouldn’t be made in an election year and should instead belong to the next administration. (AP Photo)

Publicly, the Republicans are not relenting. McConnell laughed out loud when asked about it during a Sept. 13 press conference. “Let me say once again: First of all, I don’t expect Hillary Clinton to be elected. And second, we’ve already made it very clear that a nomination for the Supreme Court by this president will not be filled this year,” he said.

Conservative activists say they are not worried. “The Left has been predicting a thaw on this since February and it hasn’t happened,” said Carrie Severino, policy director for the Judicial Crisis Network.

Others point out that McConnell or Grassley would be blasted by the Right if they relented on Garland now, while the media would portray them as caving to the administration.

“There is simply no upside for them in changing now,” said Ed Whelan, president of the conservative Ethics and Public Policy Center. That is the thinking among Republicans on the Hill too, aides say.

The one factor that does weigh in Garland’s favor, a Senate aide said, is age: Garland is 63, the oldest of any person reported to be on Obama’s short list. Clinton could easily go with someone a decade or more younger, such as 49-year-old Judge Sri Srinivasan, whom Obama considered. But Garland isn’t old enough for that to sway thinking, the aide added.

The administration has shown no sign of relenting, even with the chance of losing the nomination becoming more likely.

Kang, the former White House attorney, said pulling the Garland nomination and starting over with someone new is not something the administration would consider. “There’s no reason to think that any other nominee would do any better,” he said.

Besides, he added, it’s too late for that anyway. The administration doesn’t have the time to start the whole process over before the Senate adjourns this year.

Kang said that losing the pick to a prospective Clinton presidency wouldn’t alarm the Obama administration. “It is not about this president making the choice … It is about making the bench fully-functioning,” he said.

Should Donald Trump win, it’s a certainty that Garland will not be confirmed this fall or re-nominated next year. (AP Photo)

The further irony is that a lot of Democrats and liberal activists may secretly like McConnell’s opposition. With most polls showing Clinton ahead of Trump, few fear that anyone other than a liberal will replace Scalia on the bench. While activists like Garland, they’re not wedded to him.

“If the Democrats re-take the Senate, Hillary Clinton will get a lot of pressure to nominate someone even more progressive than Garland,” said Lena Zwarenstein, director of strategic engagement for the liberal American Constitution Society. “Garland was not on the top of everyone’s list.”

Neil Sroka, spokesman for the Howard Dean-founded Democracy for America, is blunter, saying Obama made a mistake nominating an “old white guy.”

Had he nominated a member of a minority, Republican opposition would have been a much bigger issue in the campaign, he argued. “Imagine how fired up progressive voters would have been if the GOP was opposing the first black woman candidate for the bench,” he said.

It would be hard for Clinton to resist even if she wanted to. She already owes a lot of favors to activist leaders in environmental, civil rights and labor groups for backing her over Bernie Sanders in the Democratic primary.

It still would be a bad thing if the nomination fell to Clinton because it would help to make the GOP’s refusal to allow a vote just seem like politics as usual, Zwarenstein says. Future administrations for both parties would find getting anybody through the Senate increasingly hard.

“I am worried about the precedent this sets regarding delaying tactics … This might be creating a dangerous new normal,” she said.