BALTIMORE — For most of her 84 years, Peggy Rowe has been enamored with three things, aside from her family: storytelling, laughter, and horses.

“For years, I would write stories and send them to family members or friends, and every once in a while, I sent them to the local paper. I really never dreamed that I would someday not just write a book but also publish it,” she said in an interview with the Washington Examiner. “I guess the lesson is, never stop dreaming.”

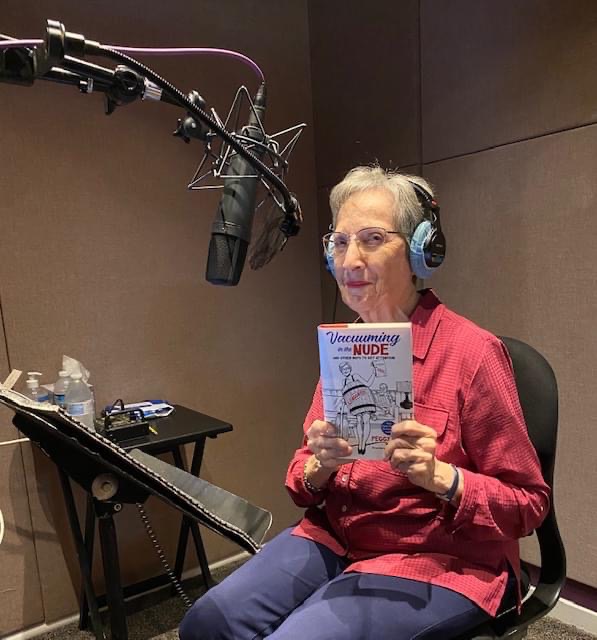

Four years after publishing her first book, she is rolling out another one, complete with a cheeky title: Vacuuming in the Nude. Rowe assures that no, she does not vacuum in the nude. The title comes from a friend who told her she had done just that.

“I was born in 1938 in Baltimore, Maryland, to the best parents ever,” said Rowe. “I was such a tomboy growing up. My mother, who was sophisticated and refined, worried about me. I also loved horses so much so that I thought I was a horse galloping around the yard,” she explained.

Rowe detailed a loving, secure environment that she knows was a blessing. “The church was a big part of our lives,” she said. “We lived just one block from our church, and every week, there were multiple activities that we attended at church.”

From time to time, her father preached to the Presbyterian congregation, while her mother was active in every phase of the life of their church.

Because of her obsession with horses, Rowe wanted to major in animal husbandry in college. “My mother talked me out of it,” she said. “‘You’re so good with children — you teach children to ride, you’ve taught Sunday school — you should be a schoolteacher.'”

Naturally, Peggy followed her mother’s advice: “I taught elementary school when I first got out,” she said. “It was there that I discovered that I could write and discovered how much fun writing actually was.” She used quirky little poems to introduce vocabulary to her third graders, only to find them making their way on to the school playground.

“One day, when I was out on the playground, I came upon a group of girls who were jumping rope,” she said. “Well, don’t you know, they were reciting my poetry from memory as they jumped rope to the rhythmic rhyme:

They carry their houses,

That’s why they’re so slow.

“I’m telling you,” she said, “I felt like a celebrity.”

Rowe said she learned early on that boys like something that’s a little risqué, “something on the naughty side, or something that makes them laugh.”

When she married and started having children, her writing continued, but it took on a different form.

“I wrote letters to relatives out of town,” she said. “My husband had a lot of relatives who lived out of town, and my mother did also.”

When her best friend was in her final days of a three-year battle with a brain tumor, she asked Rowe on her deathbed for a favor: Deliver her eulogy, and make people laugh, because of the hell she had put her family through for the past few years.

“That night, I don’t think I slept a wink, because what an awesome responsibility,” she said. She wrote the best eulogy she could, filling it with the humor that had run through the course of their relationship.

“Humor is my trademark,” she said. “Even in the eulogies I’ve written and delivered at funerals for relatives and friends, I can usually manage to include something lighthearted that brings good feelings from the people who are there, and even the family. When I heard the laughter throughout the audience … it made me feel so good that I had honored her wishes.”

She kept writing and even wrote a book or two. She received more rejection letters from publishers than she would ever care to count. It was through her own personal darkness, though, and a big push from her son, television personality Mike Rowe, that got her to keep writing books.

“In 1997, I had breast cancer and eventually developed some depression, which was so alien to my nature,” she said. “My oncologist recommended a support group.” At first, she resisted, but her eventual joining of that support group is outlined in her book. And her son Mike nudged her to write about it.

“He came to visit, and he could see the state I was in, and he said, ‘Mom, you need to write about this,’ because I had stopped writing,” she said. “I told him I could not write. And he said, ‘While you’re at it, use some humor.’ And I remember saying, ‘You don’t know what you’re talking about, Mike. I can write the story, I can make it good, but I cannot get it published. And that’s rejection. I can’t stand the rejection at this point in my life.'”

She said she pointedly told her successful son, “You wouldn’t understand that, Mike, but it just takes everything from you; it just saps your whole, you just can’t face it.”

Her son laughed. “Mom, I’m in show business. My life is rejection. You need to write about this chapter in your life, and make it good, and use some humor. Do it for the thousands of people out there who have had the same diagnosis that you have. Do it for your children. Do it for your grandchildren. Even if you can’t get it published right now, just write it, get it down.”

Peggy Rowe’s book is a must-read — a hilarious navigation of writer’s conferences, rejection letters, and observations of the quirks of aging. She never disappoints in finding laughter in the ordinary and mundane.