In U.S. politics there’s only one class — the middle class.

“A strong middle class is the bedrock of our prosperity and is the backbone of our democracy,” House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi said during a speech in Washington last week, wheeling out one of the most tried and tested populist pitches in the political lexicon.

Increasingly, concern for the middle class dominates the rhetoric of federal politics. President Obama referred to this talismanic group seven times in his State of the Union address and devoted much of his speech to proposals he claimed would help those families economically.

But what exactly is “middle-class” America? Politicians view it as crucial to their success because it is so huge, but there is no settled definition among politicians, pollsters, economists and sociologists. Nor is there a consensus about whether the middle class is characterized by an income level, a way of life or a mindset.

“It really is one of those terms that I don’t think anyone has a great answer for,” said Jennifer Silva, a sociologist at Bucknell University in Pennsylvania. “It’s just very complicated in a society that doesn’t want to say it has classes,” Silva said.

More than four out of every five Americans identify themselves as middle class in surveys. As the Great Recession subsides and the Obama era comes to a close, this vast majority and the swing voters it encompasses keep signaling in polls that they are financially stressed and politically restless. It would be a good idea, therefore, to understand what it means to be middle class, and what middle-class people hope for and dream of.

Middle-class economics

“Middle-class economics,” the catch phrase President Obama deployed during his State of the Union address, encapsulates the political salience of middle-class concerns.

It’s not a term you can find in any textbook. It is, rather, the result of Obama’s trial and effort to polish his political pitch.

“That’s what middle-class economics is — the idea that this country does best when everyone gets their fair shot, everyone does their fair share, and everyone plays by the same set of rules,” Obama explained, sounding a lot like President Clinton before him.

“Middle-class economics” is the latest iteration of a theme that Obama has been refining since he campaigning for president in 2008. Earlier versions have included a call to expand the economy from the “middle out” and decrying inequality as the “defining challenge of our time.”

Obama’s State of the Union plan included many measures aimed at helping the middle class, defined in the speech’s supporting documents as families making up to $120,000 a year. They include childcare tax credits, credits for families with children attending college, and other tax breaks and benefits.

It’s a plan forged during a time of liberal dissatisfaction with his administration over its handling of the 2014 midterm elections.

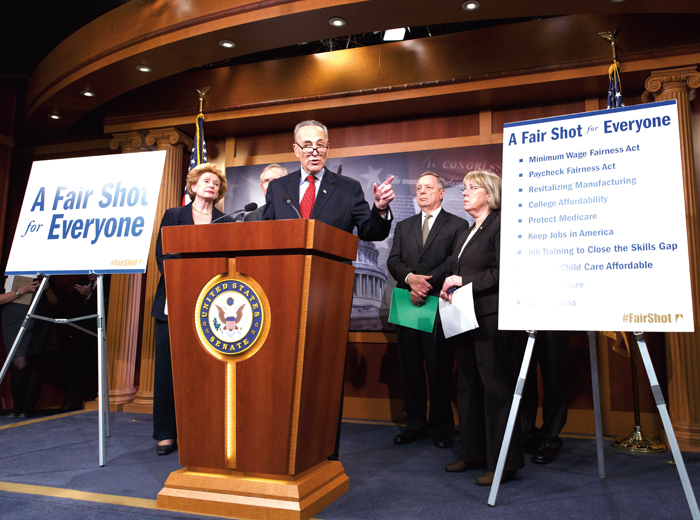

In the aftermath of the election, Sen. Chuck Schumer of New York faulted Obama for failing to place the middle class at the heart of Democrats’ policy agenda — even suggesting it was a mistake for the president and congressional Democrats to expend their political capital passing Obamacare in 2010 rather than on addressing voters’ chief concern, which was the damage done to families’ job prospects and income by the Great Recession.

There is no doubt that the middle class soured on Democrats before the 2014 midterms. Exit polls showed that Republicans had an 11-point advantage among voters earning $50,000 to $100,000.

Schumer strategized with the White House before the latest midterm elections, last November, to refocus the party’s attention away from the issue of inequality and toward lifting middle-class incomes.

“Both the White House and the Senate agreed that the decline of middle-class incomes was the most serious issue we face in this country, but the focus had to be on how to get middle-class incomes up, rather than drive other people’s incomes down,” Schumer told the Washington Post after the Democrats were routed.

The numbers

Economists often define the middle class as a range within the overall income distribution, but the range is broad and differs depending on who is setting it.

The median income for American households was $51,939 in 2013, according to the Census Bureau. The middle fifth of household incomes spans from $40,187 to $65,501.

Researchers often use the Census median as a baseline for defining the middle class. Pew Research Center, for instance, has defined the group in some of its analyses as everyone between two-thirds and double the median income, or roughly between $34,600 and $103,900. That includes 43 million households, a little more than one-third of the total population.

But such definitions can obscure more than they illuminate.

They elide the differences among races, household structures, occupations and any number of other considerations that might factor into a person’s understanding of his own definition of class.

In particular, it is awkward to use a purely income-based definition of middle class for the U.S. as a whole. The median household income in the U.S. ranges from $39,012 in Mississippi to $66,481 in Connecticut. A family of three with an income of $80,000 would be upper class in Mississippi, but squarely in the middle class in Connecticut, by Pew’s definition.

Even within states, the gradient of incomes can make the concept of a single middle class tricky. A six-figure household income would put a family just below the median in Arlington County, Va., across the Potomac River from Washington. But it would be three times larger than typical household earnings in Buchanan County, in the heart of Appalachia.

Yet it’s also not obvious that the definition of class should be separated out by region. Many people would consider living in Connecticut a middle-class privilege worth paying for. The cost of living in Mississippi may be lower, but many people would trade a bigger house and more stuff in Mississippi for a modest home and fewer toys in Connecticut.

Political risks and calculations

Economists might not agree on what the right income cut-off for the middle class might be, but it’s clear that the one Obama has been using is way off the mark.

The ceiling for the middle class set in his State of the Union proposals, $120,000, is nearly double the median income in Connecticut. An obvious explanation is that it is politically expedient to suggest that very high levels of income are nevertheless within the middle class; anyone a politician defines as being above the middle class has reason to worry that their wallet is about to be raided.

Obama has set the dividing line even higher in the past.

During the 2008 campaign, he promised to reverse the Bush tax cuts for the wealthy but keep them for the middle class, defined as anyone making under $250,000.

“If you make under $250,000, you will not see your taxes increase by a single dime — not your income taxes, not your payroll taxes, not your capital gains taxes. Nothing. Because the last thing we should do in this economy is raise taxes on the middle class,” Obama said while campaigning in Iowa just days before he was elected.

A household income of $250,000 would place a family in the top 3 percent of the income distribution in 2013. Ultimately, Republicans were able to negotiate to have the Clinton-era rates kick in even higher, at more than $450,000 for married couples.

Obama’s definition would mean that all but the top several million households in the U.S. are middle class, making it perhaps meaninglessly broad. In fact, the implausibility of such an expansive definition of the middle class has turned into a political liability for some candidates who have made similar claims.

During the Arkansas Senate race, incumbent Sen. Mark Pryor, a Democrat, accused challenger Rep. Tom Cotton of voting to raise middle-class taxes by voting for the House Republican budget, which an outside analyst had said would necessitate raising taxes on families making more than $200,000.

Cotton used Pryor’s loose definition of the middle class against him. “Senator Pryor’s comments defining the middle class as making $200,000 were simply out of touch,” Cotton said, noting that the median income in Arkansas is closer to $40,000. Cotton won the race.

Despite the trouble it has caused in the past, the $200,000 middle-class dividing line continues to feature in politicians’ plans. Chris Van Hollen, the ranking Democrat on the House Budget Committee, for instance, announced a plan for middle-class tax relief in January.

Van Hollen, whose Maryland district includes the Washington suburb of Bethesda and is one of the wealthiest in the country, didn’t intend to define the middle class with his tax plan. But it included a “paycheck bonus tax credit” that would phase out at $100,000 for individuals and $200,000 for working couples, effectively making those incomes the upper boundary of the middle class.

A way of life, not an income

Yet one reason politicians like Obama appeal to the middle class is that an overwhelming share of Americans identify as middle class even if, by any objective standard, their income places them nowhere near the middle of the pack.

One representative survey, conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2014, found that 85 percent of people said they were in the group, whether that was lower-middle class, upper-middle class, or just normal middle class. Only 1 percent said they were upper class, and 12 percent lower.

Those results suggest that “middle class” might be a subjective experience rather than something that can be measured numerically. And there may be something uniquely American in the fact that almost everyone identifies as middle-class.

John Steinbeck blamed the fact that almost no Americans think they are lower-class for the fact that communism never caught on in the U.S., saying, “I guess the trouble was that we didn’t have any self-admitted proletarians. Everyone was a temporarily embarrassed capitalist.”

The reality is that even a modest living in the U.S. is enough to place a family in the upper crust of the world distribution. The median income earner in the U.S. is in the 95th percentile for the world, according to the World Bank, and the poorest Americans are in the 60th percentile of the world distribution.

Instead of income, what best defines the middle class of America for political purposes might be its needs and desires.

“Middle-class families are defined by their aspirations more than their income,” wrote members of Obama’s middle-class task force in a report published in January 2010. “We assume that middle-class families aspire to home ownership, a car, college education for their children, health and retirement security and occasional family vacations.”

Obama reeled off a similar, if more modest, list of such class markers in his State of the Union speech. Middle-class economics, he said, “means helping folks afford child care, college, healthcare, a home, retirement.”

It’s possible that, for political purposes, the middle class could be as much defined by its fear of losing those items as it is by its aspirations to get them in the first place.

In his new book, Political Order and Political Decay, political scientist Francis Fukuyama writes that “the important marker of middle-class status would be occupation, level of education, and ownership of assets (a house or an apartment, or consumer durables) that could be threatened by the government.”

Silva, the Bucknell sociologist, used parents’ education to delineate the working class from the middle class in her recent book on the working class, Coming Up Short. If your parents went to college, you are middle-class. If not, you are most likely working-class or lower-class.

Silva’s definition helps distinguish between the oil field drill operator making $70,000 a year and the professor at a small college earning $50,000. Thanks to his upbringing as well as his own education, the professor might have more “savvy” in navigating institutions such as schools or the government. People from an educated background might have more “cultural resources,” Silva explained, such as understanding when you “should enroll your child in lacrosse instead of putting them in beauty pageants.”

Alternatively, Stanford sociologist Marianne Cooper argues that middle-class status is achieving a certain level of financial independence and security.

“Middle class, to most people, is linked with having a good life,” says Cooper, the author of Cut Adrift, a book about the middle class. “There’s different ways of defining what a good life is, but really at the core is economic security, that you could have enough money to pay your bills and have enough set aside for some kind of savings and maybe a nice vacation a few days every year. But really you weren’t living paycheck to paycheck and always kind of robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

Polling data shows that the number of people who say they enjoy that kind of security is waning, and many self-identified middle-class families report that they are straining to maintain the “good life.”

In response to a 2012 Pew Research survey, the median self-described middle-class respondent said it took an annual income of $70,000 for a family of four to afford a middle-class lifestyle.

That annual income is below that of the median married-couple household, which has an income of $76,509. But when broken down by income, it turns out that many families view “middle class” as just beyond their own earning power.

Families making under $30,000 a year, for instance, place the income required to enter the middle class as $40,000. For those making between $30,000 and $50,000, it’s $60,000.

Is the middle class shrinking?

All the available economic data suggests that many families who would identify as middle class have had their finances badly strained during the financial crisis and its aftermath.

Adjusted for inflation, real median income in 2013 was down 8 percent from 2007 in the Census data.

Since 2007, median family wealth has fallen by 40 percent, from $135,400 to $81,200, according to the Federal Reserve’s survey of families’ finances. Wealth is the total of assets, including home equity and retirement savings, minus debts. While wealth trends can be harder to interpret than income trends, the drop in median wealth over the past eight years clearly reflects the financial pain felt by families who saw the values of their homes crater.

At the same time those metrics of middle-class fortunes have been slipping, people have been less likely to tell pollsters that they are middle class and more likely to say that they are lower or lower-middle class. The self-described middle class is still a large majority, but it has shrunk slightly in recent years, as measured by both Pew and Gallup polls.

Michelle Diggles, a political opinion analyst at the center-left think tank Third Way, notes that her organization’s polling has found that people say that a middle-class lifestyle is increasingly difficult to afford. “People believe that they’re being priced out of the middle class,” she said.

In particular, the cost of each of the hallmarks of the middle class cited by the White House — housing, college and health care — has risen faster than overall inflation over the past decade.

In other words, even as the prices of some consumer goods such as high-definition televisions and smartphones have been falling, raising living standards, the costs of big-ticket items that people most associate with middle-class prosperity have risen.

“I’m not surprised that we’re starting to see shifts in people’s subjective understanding of their social class, or what the American Dream is. Because the objective indicators are changing, too,” Cooper said.

Economic insecurity has been growing over the past four decades, a trend that only intensified in the financial crisis, Cooper says. Among the metrics of growing insecurity she cites in her book are rising inequality, the declining number of people with traditional pensions rather than 401(k) or IRA retirement plans, rising annual foreclosures, and the increase in personal bankruptcies documented in research co-authored by former Harvard law professor and Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts.

Cooper also noted that the number of people saying that “people like me and my family have a good chance of improving our standard of living” has been at the lowest level in a generation in recent years, as measured by the General Social Survey, a major sociological survey conducted by the University of Chicago. The number of respondents identifying themselves as lower-class was at the highest level ever in 2012, at 8.4 percent.

“The desire to move up the class ladder has been replaced by a desire to be debt-free and to have financial stability,” Cooper said. “Americans have become much more concerned about holding on to what they have than with moving up.”

Silva, in interviewing working-class families, found that families are giving up on “traditional markers of adulthood,” such as home ownership and financial independence. Instead, they are increasingly “turning inward” to focus on personal achievements, such as improving relationships with family or friends or overcoming addiction.

Forty-year trends

The trend of rising inequality over the past four decades has been well-documented: The share of income, including capital gains, accruing to the top 1 percent of earners doubled from slightly less than 10 percent in 1979 to just more than 20 percent in 2012, according to tax return data assembled by economists Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty.

But the middle class may have fared better than it would seem apparent when looking at the rising cost of big-ticket items such as college and health insurance.

“It’s preferable, rather than picking and choosing different types of spending categories and then emphasizing ones where costs have really gone up … to kind of take the full spectrum of purchases that people make, and look at how the cost of living has changed with that full perspective,” Winship said.

In his research into the income and inequality trends, Winship has found that the middle class has done better than is often reported. When inflation is properly accounted for, changes in benefits and taxes are added to the equation, and decreasing household sizes are factored in, median household income peaked on the eve of the recession in 2007 and then likely recovered by 2011 as the safety net replaced some lost earning power. The safety net includes not only anti-poverty programs such as welfare and housing benefits, but also unemployment insurance, disability insurance, and other programs that increasingly benefit families well above the poverty line.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, Congress’ in-house budget and economic research unit, found that once the safety net and transfer programs had been factored in, inflation-adjusted median household income grew by more than 40 percent between 1979 and 2011, a year in which the labor market was still reeling from the financial crisis.

The politics of the middle class

Measuring the true level of anxiety felt by the U.S. middle class can be tricky, but the evidence is clear that it’s a large group that is receptive to a certain political pitch.

Framing a campaign or legislation as oriented to the middle class is “an important signifier to Americans that you’re talking to them and their needs,” Diggles said.

“Crucially,” she added, “a lot of people believe that what the government does isn’t to help the middle class, but it’s to help other people. Many people think that the government focuses on bailouts for the top and handouts for the bottom, but nothing for the middle.”

In polling and in focus groups, Diggles says, voters in the middle of the income distribution and in the middle of the political spectrum make it clear that they prefer politicians to be focused on the middle class.

Specifically, people are “pretty explicit” that they view Republicans as the party of the rich and Democrats as the party of the poor, Diggle says. And rhetoric about “job creators” on the Right or poverty on the Left only strikes voters as heartless capitalism or class warfare, respectively.

Instead, voters prefer politicians who talk about economic growth and opportunity.

When asked in a poll commissioned by Third Way whether they would prefer a Democratic candidate who fights for economic security, against inequality or for economic growth, respondents wanted growth, not a focus on inequality or economic security. Those polled favored a message centered on growth over one focused on security 68 percent to 21 percent. Similarly, 65 percent chose growth to 27 percent who chose inequality.

Another Third Way poll asked voters what was most important for expanding the economy, giving them a choice of: provide more economic opportunity for Americans to succeed through hard work; create more economic security so Americans can withstand life’s misfortunes; and give Americans the most amount of freedom to make it on their own.

The second option parallels the Democratic safety-net agenda and speaks directly to the kind of fears about economic insecurity documented by Cooper. Pelosi used similar rhetoric in her speech in Washington last week.

“Democrats’ commitment to middle-class economics stands in sharp contrast to the Republicans’ relentless trickle-down agenda — the agenda that drove our economy into a ditch,” Pelosi said, adding that “we must focus like a laser on strengthening the financial security of America’s working families.”

But in Third Way’s polling, the “security” message was favored by only 14 percent of respondents, while the third, mirroring Republican free-market rhetoric, garnered 21 percent. Both were crushed by option No. 1, which 62 percent of respondents chose.

Those numbers reveal why the middle class, however nebulously defined, has been and will remain at the front of U.S. politics.

To the extent that Republicans stray from talking about increasing opportunity for middle-class people, they will struggle. Presidential candidate Mitt Romney learned that lesson the hard way in 2012, when his private remarks writing off the votes of the 47 percent of Americans who don’t pay federal taxes became public knowledge. Obama was able to portray Romney as unconcerned with the fate of most families.

Republicans considering running for president in 2016 have already worked to correct their messaging.

Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., considered a top prospect for the GOP nomination, said in January that raising middle-class living standards is “the relevant issue of our time.” Rubio has been at the front of GOP efforts to devise tax plans and economic programs aimed at easing middle-class pressures, rather than spurring commerce.

Jeb Bush, the former Florida governor and brother and son of past presidents, sounded out similar themes in a speech previewing his own possible candidacy in Detroit last week.

“Far too many Americans live on the edge of economic ruin, and many more feel like they’re stuck in place, working longer and harder even as they’re losing ground,” Bush said.

On the other side, Democrats will have to avoid class-warfare rhetoric that could turn off voters who don’t consider themselves lower class.

“There are a lot more middle-class Americans than poor Americans, and a larger share of them vote. So candidates and policy makers always have an incentive to focus on middle-class concerns,” University of California-San Diego sociologist Lane Kenworthy said.

Although the poor may have a greater moral claim on politics, their cause is not a winner in electoral terms. It is “very hard to get elected on an antipoverty platform,” Kenworthy added, referring to the travails of former North Carolina Sen. John Edwards in the 2008 Democratic primary. Edwards made the theme of “two Americas,” one of people with economic security and another of the poor. Edwards struggled to gain support even among the Democratic primary electorate.

Don’t look for Hillary Clinton to make the same mistake in 2016.