YUMA, Arizona — Dozens of construction workers labor like a bustling colony of ants — only this colony is located along a 126-mile-long portion of the United States’s southern border with Mexico.

Standing 100 feet from one of these construction sites, watching workers install the concrete-filled steel beams into the ground feels painfully slow, but driving along the banks of the river and canal, the workers’ years of labor is overwhelmingly evident and compelling. The wall is up, everywhere.

Workers decked in orange vests operate the yellow construction machines in a robotic fashion as they drop the maroon pieces of steel into the ground and then repeat the step again and again. Enough piles of these steel beams sit in a nearby field of dirt to run the length of a football field.

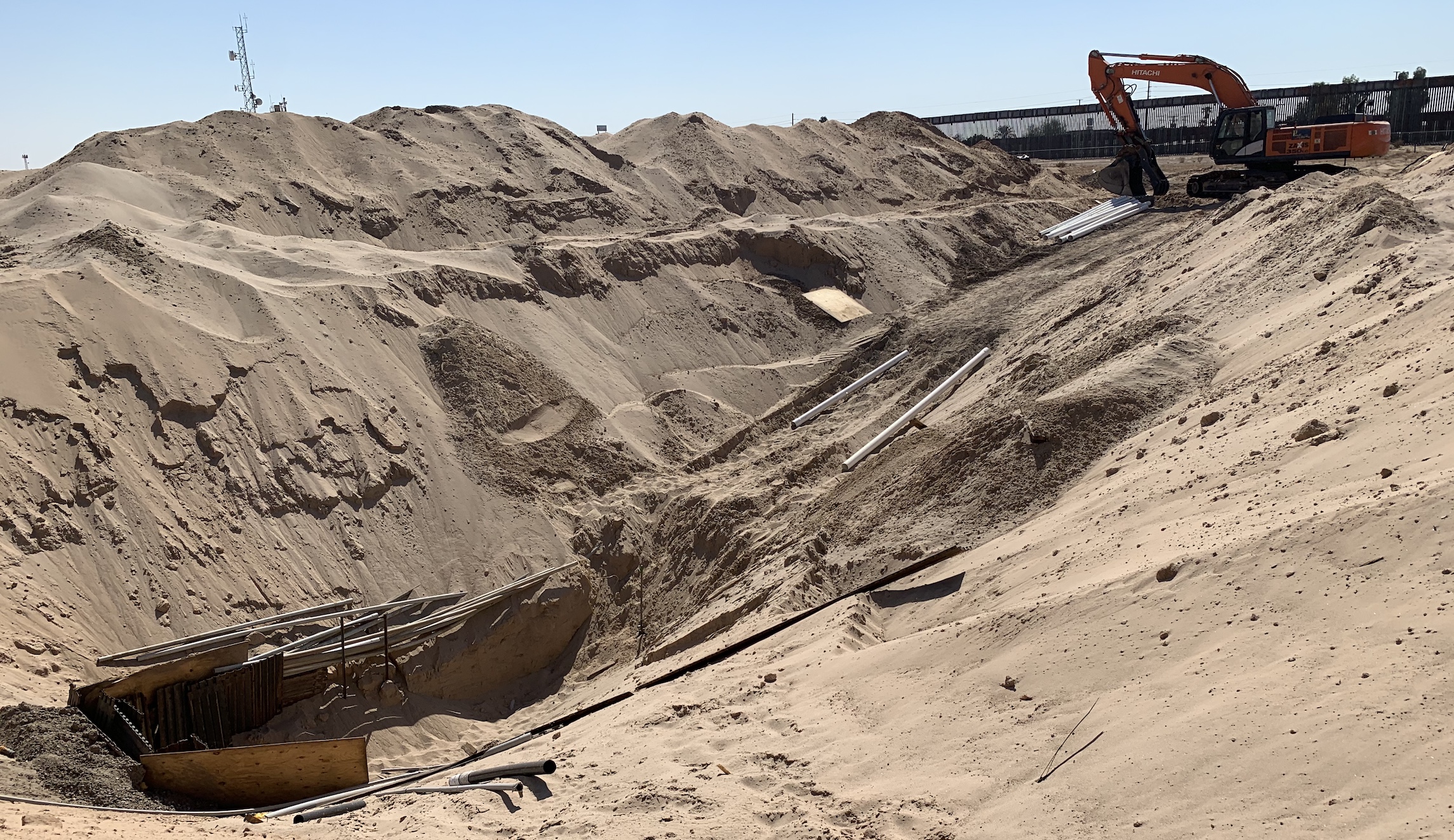

Over the past three years, construction crews here have installed 90 miles of border wall and almost 40 miles more of a parallel, back-up wall in the Yuma border patrol region, which spans from the Imperial Dunes in southeastern California to Arizona’s Pima County line. Compared to what I saw on a visit one year ago, the places on the border that Border Patrol agents show me today are unrecognizable.

The border has physically changed as a result of the Trump administration’s decision to fund projects along the 2,000-mile dividing line between two countries.

But it is also different in the way federal agents who are responsible for securing this strip of land-use infrastructure such as a wall to carry out their national security mission.

There’s always been some sort of wall

The Yuma region has had some sort of physical barrier along its border with Mexico for more than 30 years, Border Patrol’s head of the Yuma region Anthony Porvaznik tells me as we sit in his office living room. Three replica plaques that commemorate the 100-, 200-, and 300-mile ceremonies for completed miles of wall nationwide sit on the coffee table between us. The ceremonies have all been held here in Yuma, and it makes sense, given that one-third of the 370 miles of completed wall has been here in Porvaznik’s backyard.

Yuma Border Patrol has long relied on some sort of physical barrier to prevent people in Mexico from trespassing into the country here, but the Trump administration’s support for replacing dilapidated and insufficient barrier, that is, the little that it did have, was like hitting the jackpot.

“Yuma sector was the beneficiary of a lot of infrastructure back in the ’06 timeframe,” Porvaznik says, in reference to the Secure Fence Act 2006 that became law during the George W. Bush administration. That funding came through after a brutal year for agents up and down the southwest border, when more than 1.5 million illegal immigrants were arrested — far more than the 1.1 million arrests at the southern border during last year’s humanitarian crisis. The Yuma region accounted for 139,000 arrests in 2005.

“Two thousand, nine hundred drive-through vehicles came through Yuma sector alone in one year,” says Porvaznik. “We caught maybe one out of 10 of those, if that. So we have no idea what got away at that point because there was no fence.”

GALLERY: WASHINGTON EXAMINER AT THE BORDER

Smugglers evolve beyond wall improvements

Just a year later, arrests in Yuma dropped to 12,000, mostly as the result of newly funded double-layer fencing that had gone up, he says. The bits of “wall” installed throughout the region helped block illegal entries, but they were nothing more than leftover metal scraps that the U.S. military had used for helicopters to land on in rice paddy fields during the Vietnam war. Most of the metal scraps were no taller than 10 or 12 feet, and unlike the slatted steel beams that are now on the border, agents could not see what was approaching them from the south side of the border.

But as the barriers went up, smugglers evolved and found other ways into the U.S. In 2008, a suspected drug smuggler drove a vehicle over and killed agent Luis Aguilar while he was working the sand dunes of the Imperial Sand Dunes desert. The sector obtained funding and built a 16-foot-tall floating fence across 12 miles of the dunes. It blocked vehicles from driving over the border, but agents began to detect the occasional instance of smugglers moving people through the sand beneath the floating fence. Porvaznik recalled one instance when eight large buses pulled up to the Mexican side of the border, and hundreds of people exited. They then proceeded to dig holes under the dune wall and head into the U.S. Border Patrol arrested 376 people, but they also realized that the smugglers had evolved and found a way to dig holes in the sand — a seemingly impossible task.

Agents also learned that cars were sneaking into the U.S. in new unfenced places. Border Patrol inserted three-foot-tall posts in these new spots. Yet again, the smugglers evolved and found new parts of the Yuma region where there was no barrier and drove their vehicles through there. Porvaznik notes that this year, vehicle-smugglers were caught in his region attempting to move 10 Chinese citizens, 30,000 fentanyl pills, and 350 pounds of methamphetamine into the country. The dozens of miles of new wall means those drive-throughs should become a thing of the past.

A permanent fix

The back and forth between smugglers and Border Patrol continued after Porvaznik took over the region in 2015. Arrests of illegal immigrants doubled. During last year’s border crisis, up to 60% of his agents were so overwhelmed with illegal immigrant arrests, half of whom were families, that taking care of detainees took up more time than their normal law enforcement duties. The “hodgepodge” of existing barriers was not cutting it.

The new wall is comprised of six-inch square posts filled with concrete. A gap of four inches was left between each post to allow agents to see through the fence when looking straight at it. The only downside to agents is that a five-mile stretch of the border will not get new wall because the land belongs to the Cocopah Reservation. This area is where agents are seeing the most illegal immigration right now, an indication of the new wall’s success at preventing illegal entries.

Agents suspect that when the coronavirus pandemic passes and they are no longer able to immediately return illegal immigrants south of the border, as they have been able to, more will attempt to sneak into the U.S. With so many miles of new wall in place, Porvaznik thinks his agents now actually stand a chance at holding the line.

“We’re much better positioned right now to deal with that traffic when they do come than we have been in the past,” he said.