Shock ages poorly and is a sentiment ill-suited to the age. If outrage still abounds, its most irritating facet is its phoniness: With the heroic portions of prurience the internet doles out by the second, no one today can feign innocence anymore in good faith. So much the worse, then, for yesterday’s transgressives, whose obscenities have gone stale and who must, if they want their slice of fame, rely on quality, which is hard to fake and harder to achieve.

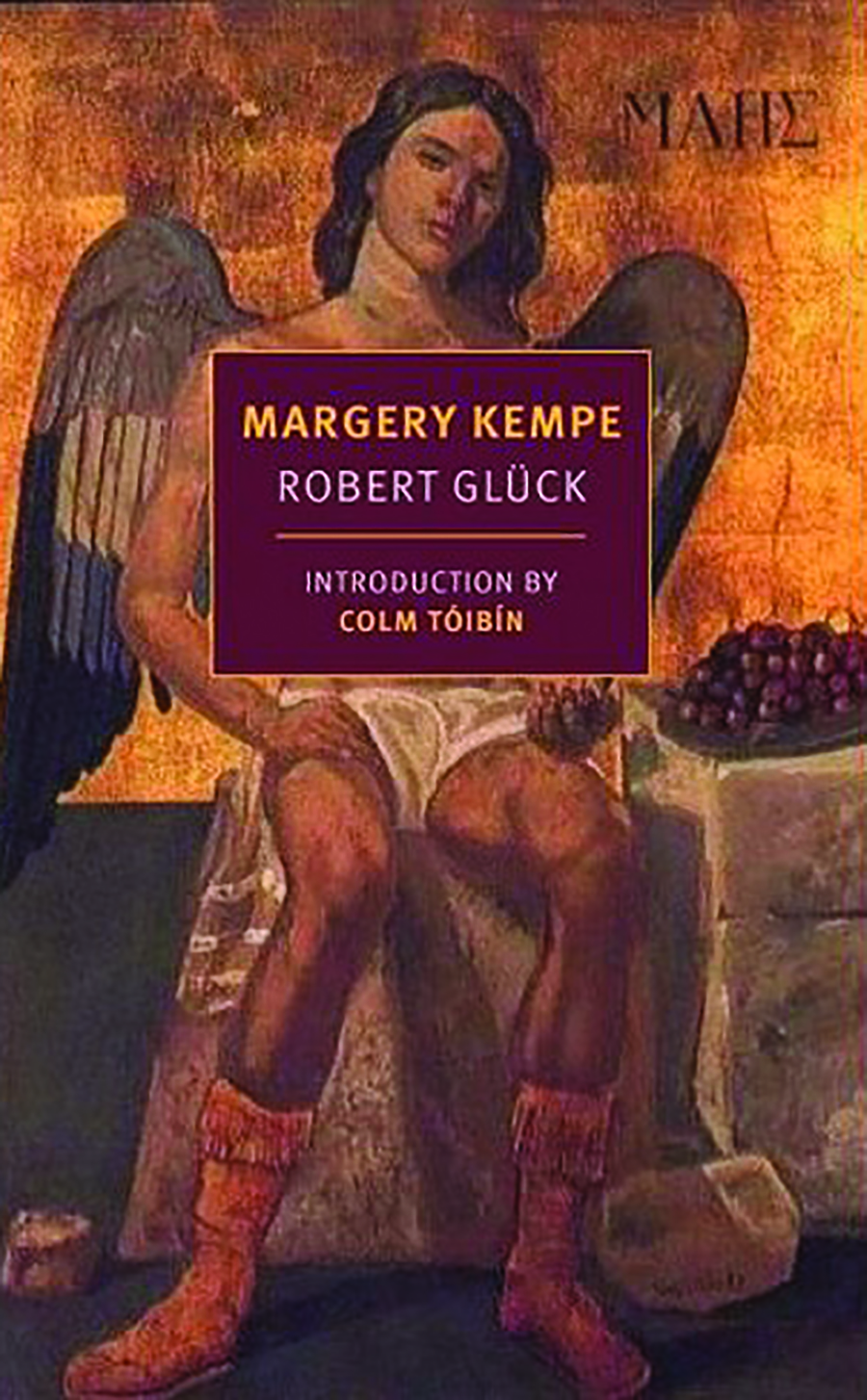

Robert Gluck is something of an also-ran among American experimental authors — an exponent of “New Narrative,” a loosely defined association of writers who emerged in San Francisco in the late 1970s and whose work is now being rediscovered, rereleased, and anthologized. Though Gluck is not the best-known of its members (who included, depending on who’s writing, Kathy Acker and the wildly underrated Gary Indiana), NYRB Classics’s reissue of his 1994 novel Margery Kempe may be the most prominent of this new wave of publications. In his introduction, Colm Toibin wisely avoids proposing a definition for what New Narrative is. Beyond a gaggle of bombast about “appropriation and pastiche” and hat-tips to the perennially fashionable Walter Benjamin and Michel Foucault, Gluck’s 2000 essay, Long Note on New Narrative gives little concrete sense of a shared aesthetics or mission. Dennis Cooper, himself often included by scholars into the movement, seems to have been right in saying of it: “There was a group of people, but there was never anything to be involved with … I think that it never went anywhere because no one could figure out what it was.”

The historical Margery Kempe was an English mystic born in the 14th century, an apparently illiterate mother of 14 who dictated what some consider the first autobiography written in English. There is debate about the accuracy of this assertion: Some researchers stress that true autobiography must depict life as a private and particular experience. Yet Margery’s chronicle abounds in detail and local color, gives insight into class politics and marital mores in medieval England, and explores an individual woman’s sexuality in ways that go far beyond what an ordinary account of religious enlightenment would demand.

Gluck’s Margery Kempe weaves together a retelling of episodes from Margery’s own book with a stylized memoir of Gluck’s own same-sex affair with a wealthy young American named L. If we take Gluck at his word, the tension between the two narratives “asks questions, asks for critical response, makes claims on the reader, elicits comments.” Having read the book, I remain uncertain what this actually means. I see the book’s central conceit as part of a literary tradition that exalts gay experience by comparing it to religious ecstasy — something Jean Genet did to masterly effect in the 1940s but that here feels like compensation for a dearth of tension, characterization, and ideas.

Gluck is a master of the coercive qualifier: the adjective or adverb that demands of the reader a respect the author hasn’t worked to earn. On the first page, when Margery is visited by devils, the experience is “overwhelmingly bizarre”; when Jesus visits her, it is “the strongest experience of her life”; Gluck and L., looking out over Central Park, “share an intense visual life.” Show, don’t tell may be a tired creative writing dogma, but it remains the case that sweeping claims demand evidence, and in fiction, this evidence is inseparable from the minute handiwork of plotting. Sadly, in his self-regard, Gluck has taken a rich vein of material — the tale of a woman who saw demons, spoke with the apparition of Christ, traveled to Jerusalem, Venice, Santiago, and even held an audience with Julian of Norwich — and has turned it into a cipher for a love affair that is part bodice-ripper, part pornography, part pop psychology, and part pedestrian rehash of the radical credos of yesteryear.

In his early visitations to Margery, Gluck’s Jesus adopts the guise of a poète maudit. Bony, weepy, with “tiny nipples” (as the author never tires of repeating), he whispers to Margery, “I’m so abandoned.” After their second, grotesquely detailed encounter, she has “awakened his self-esteem.” For a time, there is synergy: “Margery impressed Jesus, who motivated her.” But Jesus turns out to be a typical man — aloof, exasperated with Margery’s demands for affection, and bent on tarting her up to make her attractive to other men. Soon, Margery realizes that “Jesus must be seeing someone else.” After her many pilgrimages and hardships, including trials for heresy, she bawls Jesus out for being spoiled and emotionally distant: “You will never know anything till you have to work for a living. You bought me clothes and took me to Italy — you never gave me a penny of real support.”

What I have spared readers so far is the marrow of the book: an insistent, petulant lewdness that feels less like literary provocation than the drab drolleries of a high school pervert. Curiously, Gluck reserves the strong stuff for the medieval characters (plus a jaunt back in time for cringey description of Mary and Joseph au naturel), while preferring more ethereal language for his relationship with L.: “The forward momentum of my longing becomes a form of velocity, membranes and aspirations surging toward a foreign airport … ” Meanwhile, Christ’s body is placed on embarrassing display, randy friars copulate with maids and one another, and hardly a single woman appears without some derisive reference to her anatomy.

One imagines Gluck would like to say that all of us harbor the unutterable longings and obsessions his book examines, but we don’t, or not really, and if we did, it wouldn’t matter, because humility, sympathy, understanding, and humor are not reducible to this mishmash of the erotic and the scatological. To paraphrase Michel Foucault (strangely, his American acolytes seem less fond of this part of his work), the persistent critique of sexual repression in society is inseparable from the compulsion to embrace sexuality, to talk and hear about it nonstop, to accept the dubious supposition that its secrets somehow compose the deepest and truest layer of the self. Lacking the Marquis de Sade’s programmatic anarchism, the poignancy and documentary intelligence of John Rechy, or the assorted other virtues of his myriad forerunners in literary tresspass, what Gluck offers here is a mere index of preferred objects of lascivious contemplation. That is fine for him, but it is vanity to deck it all out with a few fancy phrases and call it art.

Adrian Nathan West is a literary translator, critic, and the author of The Aesthetics of Degradation.