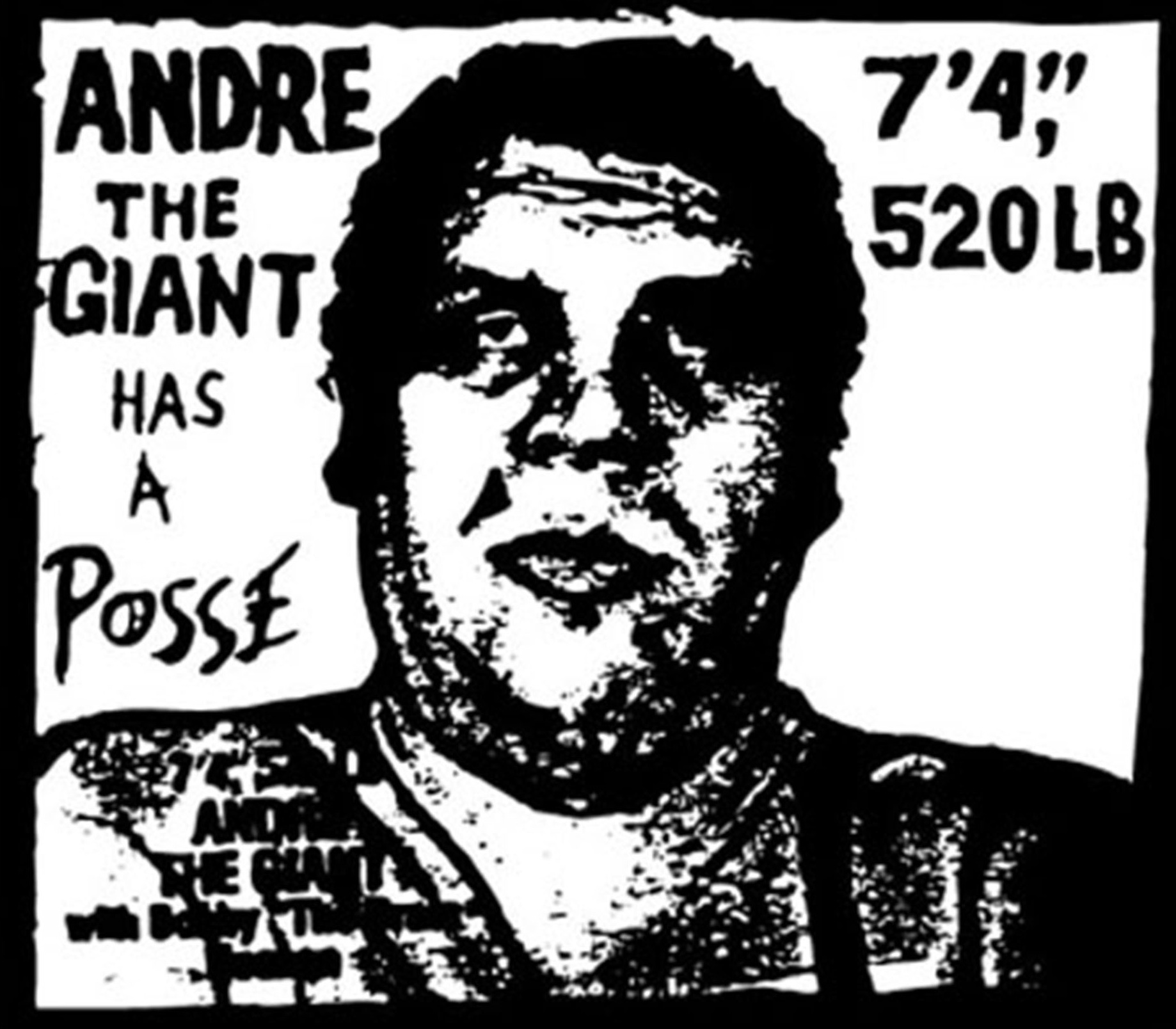

Let’s start with the obvious: Andre the Giant, subject of a new documentary from HBO, was huge. The wrestler seemed almost to have stepped out of legend or myth. Billed at a whopping 7-foot-4 and 477 pounds, he was a veritable Grendel, with deep-set eyes, frizzy hair, and a protruding jaw. Dubbed by promoters the “Eighth Wonder of the World,” he wore size-24 shoes and a size-24 ring, and his wrists were nearly 12 inches in circumference. In addition to the incredible diet necessary to sustain such mass, he could consume, according to some estimates, up to 7,000 calories of alcohol a day. In a career spanning 27 years, six continents, and over 5,000 matches, he became a cherished icon of professional wrestling—and was arguably among the most influential athletes of the 20th century.

André Roussimoff was born in 1946 in Molien, a small commune north of Paris; at 11 pounds as a newborn, he was larger than average but not abnormal. His parents, both Slavic immigrants, were farmers. His early years were unexceptional; “Dede,” as he was called, loved soccer and mathematics.

Then he began to grow. By the age of 12, he was over 6 feet tall and weighed more than 200 pounds. He soon grew so large he could no longer fit on a school bus. Fortunately, in a strange moment of serendipity, André’s father had become friends with Samuel Beckett, the playwright, who lived nearby. Intrigued by this youthful towering colossus, Beckett drove André to school every day. (Beckett would not be the only famed writer to take an interest in him; late in André’s life, William Goldman would call himself a “lunatic fan of André’s.”)

Young André eventually grew too large to sit normally in a car and became known locally for driving around with his head poking through the sunroof. By his late teens, after unfulfilling apprenticeships in woodworking and in a car factory, he had not only outgrown the school bus and cars, but Moliens itself. Unsatisfied by his prospects, André, who was still growing bigger, dreamed of doing bigger as well. So he moved to Paris, where he worked as a mover during the day and began wrestling at night. He was soon discovered by the Canadian wrestler and promoter Frank Valois, who became his manager in 1966. With Valois at his side, André would tour the world, wrestling in the United Kingdom, Australia, and Africa before settling first in Japan and then in Montreal.

Professional wrestling then, like now, was more show than genuine sport; it had long operated in a mode that would come to be called “kayfabe”: Matches were staged or even scripted for maximum drama and audience draw. Outrageous personalities predominated, dating back at least to Gorgeous George in the 1940s and ’50s. (George had been the among the first wrestlers to use entrance music.) André may not have fit in a car, but he was a natural fit for this alternate reality.

It wasn’t long before he caught the attention of Vince McMahon Sr., the founder of the World Wide Wrestling Federation. On McMahon’s advice he adopted his famous moniker: Andre the Giant. And, again heeding McMahon, he changed his wrestling style. Instead of employing acrobatic maneuvers as he had before, he would become an immovable object. He would endure repeated blows from his opponents, giving the impression that they might win—only then to crush them with ease. He debuted with the WWWF on March 26, 1973, defeating Buddy Wolfe in New York’s Madison Square Garden.

In those days, wrestling was more regional than national in character, and to preserve Andre the Giant’s novelty—to keep people in any given place from getting sick of him—McMahon would keep him on the move, touring from territory to territory, fighting new opponents. For the next decade and a half years, André remained almost entirely undefeated.

The world of professional wrestling underwent a major shift during this period, thanks to the rise of cable television and the impresario who took advantage of it: Vince McMahon Jr., who bought out his ailing father in 1982. The younger McMahon was intent on gaining national control of the industry. He did so by improving production values and adding even more theatricality to his shows—cranking up the exhibitionism. (McMahon and his colleagues reportedly coined the phrase “sports entertainment” to describe their product.)

HBO’s documentary Andre the Giant captures this transformation of wrestling—and André’s role in it, showing footage of the smackdowns he doled out to adversaries in the ring well into the 1980s. And it also focuses on the aspect of his career for which he may be best remembered in the future: his hilarious role in the 1987 movie The Princess Bride.

Despite difficulties with the language barrier—he never entirely mastered English, and his accent and size combined to give him a strange voice when speaking the language—André was made for the part of Fezzik the giant. Or, rather, the part was made for him: André had served as the inspiration for Fezzik when William Goldman first wrote The Princess Bride as a novel.

Being on set came naturally to André—understandably so, as he had been in the limelight his entire life. The other actors appreciated his gentle, funny manner and his generosity of spirit. In the documentary, Robin Wright (the actress who plays Buttercup) remembers regularly feeling cold while filming in England; to warm her up, André would tenderly place his hand over her head, his fingers so long that they went down to her nose.

But André was notably infirm while on set in the summer and fall of 1986. Overdue for a back surgery and beset by chronic pain in his knees, he floundered through his wrestling scenes with the much-smaller Cary Elwes (the actor who played Westley). In fact, André’s pain was so debilitating that giant who had once tossed 300-pound wrestlers around the ring couldn’t even catch 100-pound Robin Wright when she was supposed to fall into his arms at the end of the film. She had to be hooked up to cables and lowered into his grasp weightlessly.

Early in his career, while still wrestling in Japan, André had been diagnosed with acromegaly, a disorder in which the pituitary gland produces too much growth hormone. He was told he would not live past 40 (the age that he was during filming). Though the effects of the disorder were irreversible, André was told that steps could be taken to attenuate future symptoms. But he eschewed treatment, worried it would interfere with his wrestling career. So his body continue to grow—gradually exceeding the strength of his joints and organs.

Given his increasing debility, it was clear that André’s wrestling career would soon have to end—and the documentary does a good job of explaining the background and the importance of his last major fight, a match against Hulk Hogan on March 29, 1987. Hogan was by far the most notable frontman for Vince McMahon Jr.’s new era of wrestling, and other than McMahon he arguably bore the largest portion of responsibility for the success of the World Wrestling Federation. With an outsized personality, bright yellow leotards, bleached mullet, an unnatural tan, and steroid-induced muscles, he drew an enormous number of fans. This was the age of “Hulkamania.”

The Hulk-Andre faceoff was a pivotal moment. Not only did it symbolize the transition from regional wrestling, from which Andre the Giant had emerged, to the era of national TV, in which Hogan reigned, but it also was a passing of the torch from the older of these two friends to the younger. Within the strange, fictional moral universe of professional wrestling, Andre the Giant “turned heel” for the match—that is, André, who had not played a bad guy since his early days in Japan in the ’70s while fighting as “Monster Roussimoff,” would for this last match the part of the villain. Hulk Hogan was the hero.

André’s “back was really bad,” Hogan tells the documentarians. “He probably shouldn’t have been in the ring.” Hogan recalls planning the fight meticulously, working around André’s many handicaps, leaving only the fight’s conclusion unchoreographed.

The match was the highlight of Wrestlemania III. Andre the Giant starts the fight with a right cross, countered by markedly more nimble Hulk Hogan. Hulk responds with pugilistic fury: A roundhouse punch to the head. A second. A third. Then an attempt to pick up his opponent for a bodyslam—only to collapse under his enormous weight. Andre absorbs each strike effortlessly, showing only modest signs of wear; these pros are very good at faking and taking their hits. After Hogan collapses beneath him, Andre takes control of the fight. There are several more exchanged blows and he clasps Hogan in bear hug—he is unable to lift Hogan off the ground due to his injured back—and continues to dominate for several more moves.

Then Andre winks at the camera. The tides shift in Hulk Hogan’s favor. With a spectacular, unanticipated bodyslam and leg-drop, Hogan defeats André. The crowd goes wild.

For me, someone too young to have known that era in professional wrestling, HBO’s Andre the Giant was an enormous pleasure to watch. The pacing is perfect, the soundtrack is moving, and even diehard fans will enjoy the never-before-seen footage. There are plenty of poignant stories about his gentle nature and mischievous sense of humor. Arnold Schwarzenegger tells the filmmakers about his friend’s insistence on paying whenever they went out to dinner together. Once, when Schwarzenegger tried to pay, André picked him up and placed him on an armoire before going to pay himself.

But the documentary is at its most powerful in revealing the extent of André’s suffering—both physical and psychological.

His whole life, André had struggled to navigate a world that hadn’t been built for him. Life on the road could be grueling. Often hotels would have difficulty accommodating him, struggling to find a bed that could support his weight. On flights, he refrained from drinking because he was too big for airplane lavatories. When he did have to go, the stewardess would pull a curtain in front of him so he and he could relieve himself in a bucket. “It’s difficult everywhere I go,” he says on camera during the filming of The Princess Bride. “They don’t build anything for big people. They build everything for blind people, for crippled people, for some other people, but not for big people. So we have to fit in there and it’s not too easy all the time.”

Then there were the jeers, insults, the gawking. In the documentary, longtime wrestling announcer Gene Okerlund recounts that André told him “You know, boss, sometimes they laugh at me, they point at me, it hurts my feelings.”

Andre the Giant’s chief failing is that it tries to turn its subject into a saint-by-suffering. It could have gone further in probing his dark side. The documentary does not, for example, reveal the full scope of his wrongdoings. He once provoked fellow wrestler Bad News Brown with with explicit use of the N-word. He allegedly targeted another contemporary, James Harris (more famously known as Kamala) with racial epithets. He also famously brawled outside the ring with Blackjack Mulligan on several occasions. In August 1989, he was arrested by an Iowa sheriff for assaulting a cameraman.

And the film gives short shrift to André’s complex relationship with his daughter, Robin Roussimoff. He fathered her out of wedlock, after having been told that he was sterile—and he denied paternity until a court-ordered blood test proved otherwise. When he finally accepted Robin as his daughter, he and his mother resolved to keep her far from the world of wrestling. A 2015 graphic novel about André’s life—Easton Medri’s Closer to Heaven—goes into much more detail about their relationship, even including a foreword written by Robin. In it, she reveals that his long periods of absence—the road life of a professional wrestler—were interspersed with genuine attempts to connect with her. He once apparently even invited her to come live with him; Robin refused, out of loyalty to her mother. Their contact was sporadic through the rest of his life.

Still, Robin does appear in the film. “I think he was a good man,” she says of her father.

As André’s health declined, he had more and more difficulty walking. For years, he resorted to alcoholism to numb the pain and spent increasing long stretches of time at a farm he had purchased in North Carolina. There he could live in peace, without staring eyes. There he could reconnect with the agrarian spirit of his childhood in rural France.

“We do not live long, the big and the small.” André once remarked to his Princess Bride costar Billy Crystal. He died of congestive heart failure on January 27, 1993, in a hotel room in Paris. He had been in France to visit his dying father, whose death preceded his own by only a week. When he died, his North Carolina estate was left to a sole beneficiary: Robin Roussimoff.

There is a perennial temptation to look back on the life of a man and cast him in the role of the hero or villain. Few know this as well as professional wrestlers, who make a career of playing one or the other. But this is shortsighted. Ultimately, Andre the Giant, the monster in the ring, was all too human. Let’s leave it at that.