As a young, single woman in the late 1980s, my mother enjoyed reading the comic strip “Cathy.” She found Cathy’s boy troubles and diet failures comforting, if not always funny, because whatever flaws my mother had, at least she was never as pitiful as the comic’s eponymous heroine.

Over the years, “Cathy” creator Cathy Guisewite has fielded plenty of similar feedback, as well as more glowing or more frustrated responses, from fans who felt understood to detractors who thought the whole of womankind had been misrepresented.

Reading the comic strip as young, single women in 2019, some other readers and I find most punchlines hackneyed: I bought more shoes again! I ate too much chocolate again! I called that loser guy again!

Yet the claim that Guisewite may be “just another example of compromised feminism,” as women’s website the Cut posits, seems overly simplistic. Cathy was never the CEO type. She’s fallible, humorously so.

Cathy’s role on the comics page was simply to represent, with a wisecrack or two, the mixed messages with which young career women were wrestling as the turn of the century approached. At least, that’s how Guisewite explains it in her new book.

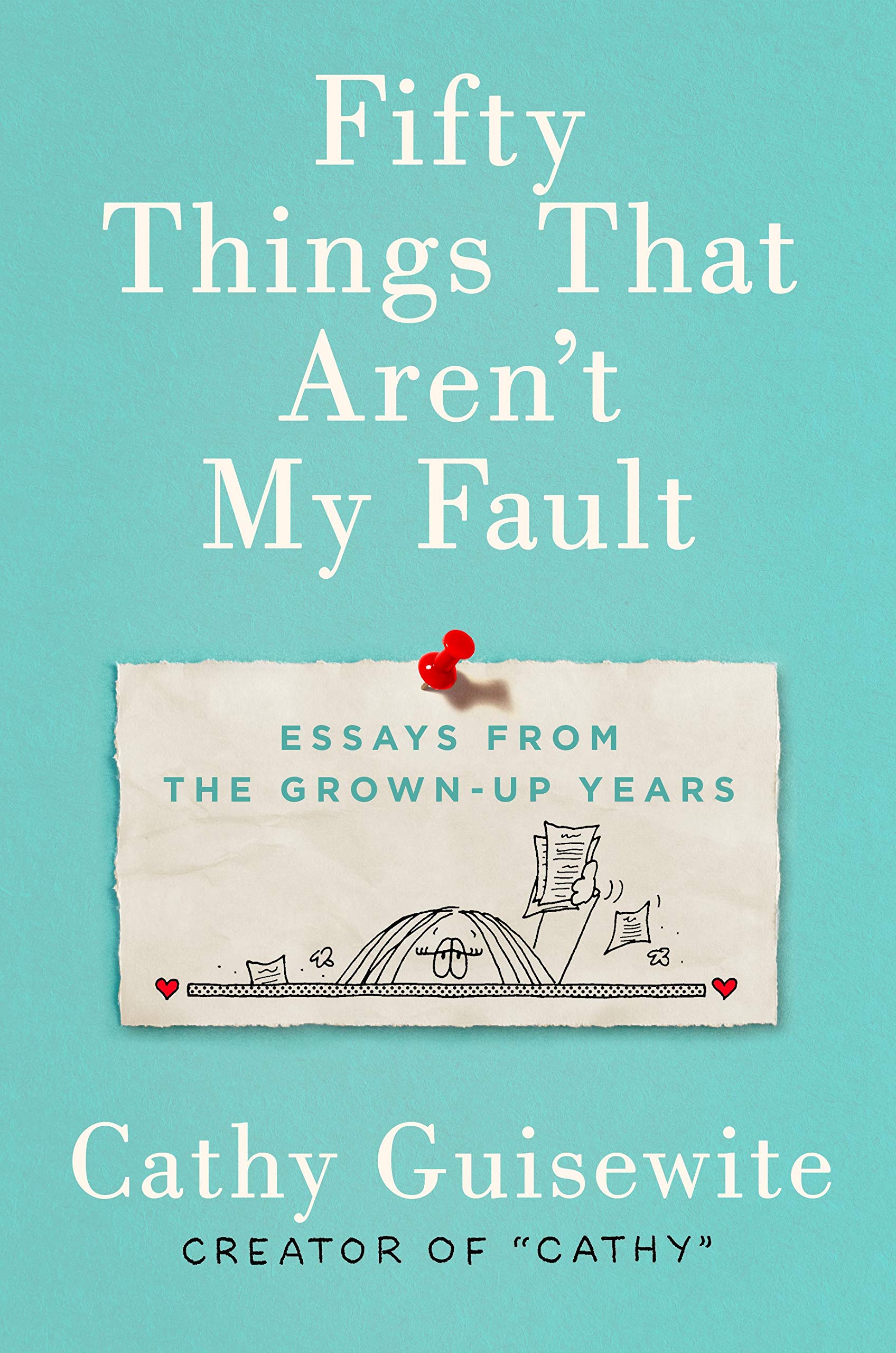

For 34 years, Guisewite labored over the comic strip, which at one point ran in 1,400 papers around the world. It ended in 2010, and she’s followed up her retirement by releasing an essay collection in April, Fifty Things That Aren’t My Fault: Essays From the Grown-up Years.

Better than her comic strips, Guisewite’s Fifty Things That Aren’t My Fault achieves empathy with less triteness, and it answers some of the criticism she’s received from feminists over the years.

The things that aren’t Guisewite’s fault include getting stuck in a sports bra in the dressing room, waving her hand at an automatic soap dispenser that doesn’t work, and having to teach her nonagenarian mother how to drive again. Unlike her comics, which boxed her commentary in four panels, Guisewite spends each chapter elaborating on what it feels like, at least from her perspective, to be a woman in the 21st century.

“There’s honor in raising one’s voice about the big problems,” Guisewite writes. Problems such as unfair practices and harassment. “There’s no honor in mentioning what happened last night with nine ‘100 Calorie Packs’ of Mini Oreos.”

Critics look at Guisewite as a woman who never really “got” second-wave feminism, or third-wave feminism, for that matter. When women were flooding the workforce in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, where was Guisewite? After 1976, she was behind a desk drawing “Cathy.”

But Guisewite kept working in the corporate world until 1980, when she quit to write “Cathy” full time. She recognizes that women have faced bigger problems than those that occupy the comic. But, she asks, what about the small ones?

Guisewite is both humorous and sentimental as she describes the pains of getting older and no longer fitting into her shoes, taking care of her 19-year-old daughter and taking her bra shopping, and caring for her 90-something-year-old parents and convincing them wireless phones are actually a good idea.

At one point, Guisewite describes how her quest to frugally retain a piece of Bubble Wrap sends her to three different stores, buying and returning $79.90 in storage supplies so she can save wrapping materials like her thrifty mother. At the end of it all, she imagines her mother tossing in the night, awakening to the thought, “Do you suppose she ever thinks of me?”

Anyone who’s ever been a daughter, or anyone who’s ever had parents, will relate to her complicated relationship with her mother, a line between respect and independence that she straddles. It’s the kind of paradox she explored in “Cathy,” with the character eating a whole pie in one comic strip because her mother advised her not to have a slice. The comic strip seems a little on the nose, but Guisewite’s recollection of the same dynamic in her book feels sweet. If “Cathy” suffered from making relatable problems too stereotypical, Fifty Things That Aren’t My Fault gives them room to breathe.

Guisewite recounts another memorable scene, one in which she spends way too much time in a public restroom, waiting for the automatic soap and water to register her waving hand. Nothing. She finally gives up, digging through her purse for a bottle of hand sanitizer. She triumphantly squeezes a glob onto her hands and turns to leave. Then she changes her mind, walks back, and deposits the bottle onto the counter.

Guisewite’s life may feel like a mess, but at least she can remind others they’re not alone.

Madeline Fry is a commentary writer for the Washington Examiner.