Pope Francis is not a politician, but likes a good political dustup. And the Holy Father couldn’t have packed his trip to the United States this month with more politically charged issues.

From his port of origin (he’s arriving from Cuba), to his occasion for Mass in D.C. (canonization of a controversial Spanish missionary), to the small church he will visit in Harlem (site of a battle between the church hierarchy and a group of poor church ladies) every aspect of Francis’ visit pushes a cultural or economic hot button. Even the readings at his Sunday Mass in Philadelphia echo class warfare debates over inequality.

He’ll do all of this amid a pitched battle on Capitol Hill over abortion, and as a multitude of candidates vie on social issues to be their party’s presidential nominee.

Francis, a veteran of political scraps in his native Argentina, seems to have an instinct for political nerves here, too. Yet, while he comments on issues uppermost in public debate, he does so from a perspective rare in the U.S., and especially in Beltway circles.

Sometimes he’s Left, sometimes he’s Right, but usually he’s not quite either, and he is certainly not a partisan in Democrat versus Republican terms.

One reason is simply the difference between the Catholic Church and American politics. They have always had overlapping, but ultimately divergent concerns.

“People who think the world revolves around Washington politics don’t realize that the Pope is a global leader,” said Francis Rooney, who was U.S. ambassador to the Vatican for four years under President George W. Bush.

“This guy is the head of a universal church,” said theologian and papal expert Lawrence Cunningham of Notre Dame. “He is alert to what is going on in the world well beyond the North American and Western European world.”

But it’s also Francis himself. This first pope from the Western Hemisphere seems somehow more alien to the U.S. than his predecessors.

Francis’ Argentine pedigree and his more pastoral demeanor position him further from the American mindset than other recent church leaders. This creates confusion for those who try to watch Pope Francis through an American political lens.

It makes his visit a learning opportunity both for Francis and for Americans unused to seeing things his way. That’s especially so for those who believe the Acela corridor is the center of the world.

Pope Francis, right, greets Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI, at the Vatican.

The liberal pontiff?

The New York Review of Books, Slate, Sarah Palin and many others have called Francis a liberal. In ecclesiastical matters, many argue that he has accumulated a liberal record. In his appointments, Francis has planted himself on the church’s liberal side.

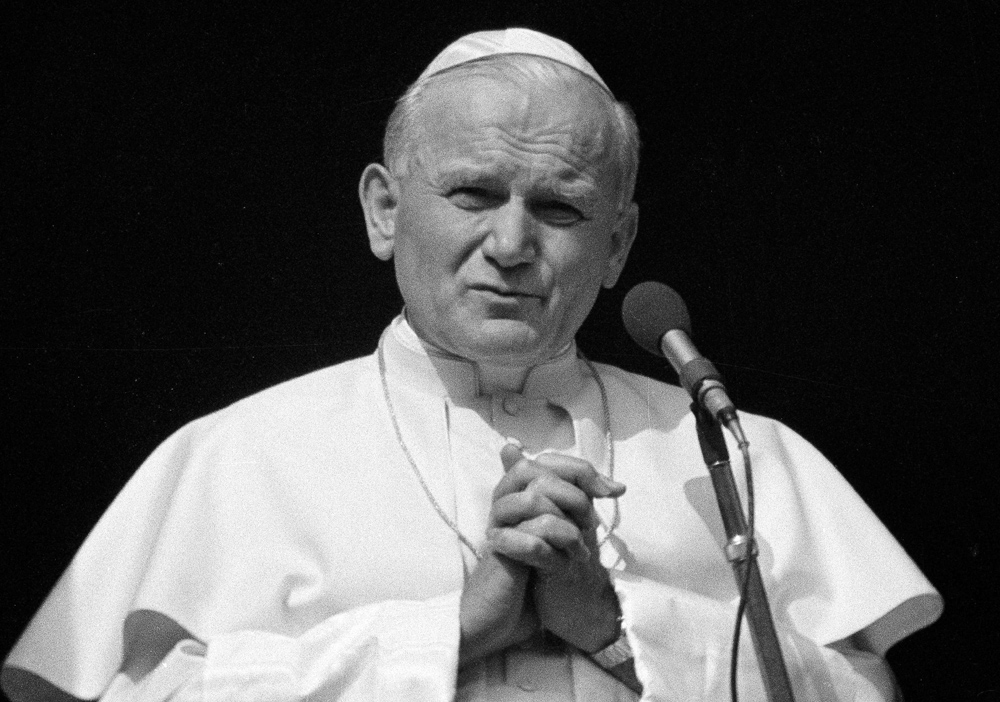

But on economic and social policy, Francis isn’t substantially more liberal than his “conservative” predecessors, Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI.

“I don’t think the categories Left and Right are very useful for understanding the pope, if you understand those categories in American political terms,” Cunningham said.

Hints toward liberalism are plentiful at first glance: his criticism of unfettered capitalism, his invocations of the poor, his warnings about the environment and climate change, and his “Who am I to judge?” language on sexuality.

On the other hand, Popes Benedict and John Paul II were heroes to American conservatives, thanks to their firm stances on the life of the unborn, and John Paul II’s opposition to communism.

But what actually sets Francis apart from his recent predecessors is mostly rhetoric, emphasis and the way the media covers him.

“Spanish is a blunter language” than German and Polish, the native languages of Benedict and John Paul II, Rooney said. “Because of the bluntness of Spanish, he’s perhaps less nuanced than some of his predecessors.”

It’s also a matter of personality. “Never in the era of mass media have we had a pope who speaks publicly the way Francis does,” said Stephen White, fellow in Catholic Studies at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. “His informality and candor are part of his personal charm, but his colloquial style can sometimes lead to misinterpretation and confusion. Pope Francis knows this; he obviously thinks it’s worth the risk.”

On substance, the last three popes largely agree on issues where church teaching intersects with U.S. politics.

Francis unflinchingly maintains the church’s ancient teaching about the sanctity of human life and total opposition to abortion. Although he has urged Catholics to drop their “obsession” with such issues, Francis would also stand with his predecessors against gay marriage. In fact, he clashed with the Argentinian government when it was expanding marriage to include same-sex couples.

On economics, Francis would look more like a Democrat than like a Republican, but so would his “conservative” predecessors.

“If we refuse to share what we have with the hungry and the poor, then we make our possessions into a false god,” Pope Benedict said in 2008. Two years later, Benedict said, “Economic life should properly be seen as an exercise of human responsibility, intrinsically oriented towards the promotion of the dignity of the person, the pursuit of the common good.”

Pope John Paul II addressing a crowd of 80,000 from the window of his studio at the Apostolic Palace, Vatican City. (AP Photo)

Benedict and John Paul II opposed the Iraq War. Francis has been more hawkish, calling for western military intervention in Syria. All recent popes have inveighed against capital punishment.

These are the views of popes because they are the views of the Catholic Church. The Catechism of the Catholic Church is unambiguous on abortion and on marriage being between a man and a woman. On economics, the Catechism cites St. Catherine of Siena: “Excessive economic and social disparity between individuals and peoples of the one human race is a source of scandal.”

The Francis difference, on the economic and social issues with which Washington and New York are most concerned, is largely one of tone and emphasis.

Comparing Benedict and Francis, Cunningham said, “The big contrast between the two has to do with background.” Benedict was a “German academic. He spent his whole life in he world of intellectuals. He had very little pastoral experience.”

Francis has not explored the theoretical avenues of theology so much as he has combed the real alleyways of the villas miserias back home. “His experience in the streets of Buenos Aires can explain how he sees things differently from his predecessors,” Cunningham said.

Where Benedict was a theologian and John Paul II was a philosopher, Francis is a shepherd.

As Francis arrives, Americans can perhaps best understand him as the pastor of a parish that is the whole world.

Acting Cuban President Raul Castro, right, is seen at the Karl Marx Theatre in Havana. (AP Photo/ Javier Galeano)

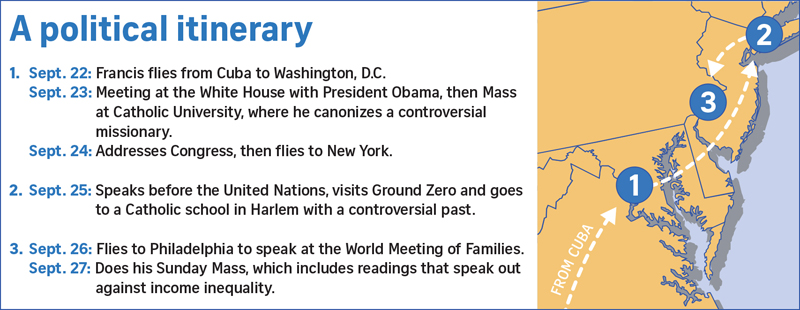

The political itinerary

Francis, when he was Archbishop Jorge Bergoglio of Buenos Aires, never shied from political fights. Allies of Argentinian President Cristina Kirchner reportedly called Bergoglio “the opposition.” When he was named pope, she barely congratulated him.

Francis will keep up his political agitation in the U.S. Nearly every detail of his visit could trigger political debate.

Even his layover is political: Francis will arrive in D.C. Sept. 22 from Cuba, where Washington banned travel for decades until the recent thaw, which Francis helped facilitate.

Francis wrote to President Obama in summer 2013, calling on him “to resolve humanitarian questions of common interest, including the situation of certain prisoners, in order to initiate a new phase in relations” with Cuba.

When Obama visited Rome in March 2014, Francis, according to media accounts, brought up relations with Cuba again. The Vatican’s secretary of state also reportedly discussed the issue with Secretary of State John Kerry in December.

In 2013 and 2014, the political foreign policy debate here had little to do with Cuba, but was focused on the Islamic State, Israel, Syria and Russia. But Pope Francis made it a priority.

His position doesn’t fit neatly on the political spectrum. Support for normalization with Havana usually comes from pro-trade libertarians and dovish liberals.

On his second day in the states, Francis will go to the White House to meet Obama. It will be their second meeting. They disagree sharply on issues such as abortion and marriage, but find common ground on inequality and the environment.

Later that day, the Pope will celebrate his first Mass, on the campus of Catholic University, where he will canonize Junípero Serra, an 18th century missionary priest who was, until recently, recognized as a hero of Californian history.

Serra was born in Spain in 1713, but carried out his life’s work in California, building missions and converting the Native Americans to Christianity. The cities of San Diego, San Francisco and Santa Clara are among dozens that got their names, Spanish and named after saints, from Serra.

Some Native American activists and their political allies now denounce Serra as a symbol and even an agent of the Spanish imperial abuse of native peoples.

Francis isn’t ignorant of the political turmoil and anger in Native American communities over Serra and western missionaries. He said in Bolivia in July: “Many grave sins were committed against the native peoples of America in the name of God … I humbly ask forgiveness, not only for the offenses of the church herself, but also for crimes committed against the native peoples during the so-called conquest of America.”

Thursday morning, the pope will address Congress, the first pope to ever do so. He will speak amid active political debates over diplomacy with Iran, abortion policy and the definition of marriage, among others.

He then will fly to New York and the next day will address the United Nations before visiting Ground Zero. Later Friday, Francis will visit a Catholic school in Harlem. One might expect a visit to a parochial school to be free of politics, but this is Francis. Our Lady Queen of Angels, thanks to its recent history, is perhaps the most politically controversial parish in the U.S. Students at Queen of Angels School are from poor families and largely from immigrant parents. But the parish church was shut down last decade by the Archdiocese of New York because of thin attendance.

The handful who attended Mass there at the time included a few fiery community organizers from the radical “liberation theology” tradition of the church. In February 2007, shortly after the archdiocese announced the closing, about 40 peaceful protesters occupied the pews. A couple of hours later, police told the occupiers to leave. Eventually, organizer Carmen Villegas and five others were hauled out in handcuffs.

For months afterward, many of these women held a service of sorts in front of the church, while also fighting to reopen it. The archdiocese didn’t budge even for Villegas’ funeral in 2013, or for the 2012 funeral of a fellow protester. Both funerals instead took place on the sidewalk.

On Saturday, Francis flies to Philadelphia, where he will speak at the World Meeting of Families, the original purpose for his entire trip. There, he will say his only Sunday Mass in the U.S. Once again, expect some political fireworks.

Bible readings at Catholic Masses are usually the same at every church, and the schedule is set years in advance. The second reading at Pope Francis’ Sunday Mass is from the Epistle of James. “Come now, you rich, weep and wail over your impending miseries,” the reading begins. “You have stored up treasure for the last days. Behold, the wages you withheld from the workers who harvested your fields are crying aloud; and the cries of the harvesters have reached the ears of the Lord of hosts.”

The media filter

It’s a reading that news media can be expected to conflate with their own political views. Pope Francis is often misunderstood, Garvey says, in part because Americans almost always get his message “filtered through the lens of the media.” American media’s emphasis and focus will be different from those of the pope and his speechwriters.

Journalists like clean narratives, and with Pope Francis, the simplistic narrative is that he’s “the liberal pope.”

The day after the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments about gay marriage, Pope Francis dedicated his Wednesday public homily to marriage.

“Jesus begins his own miracles with this masterpiece: a man and a woman,” the pope said. “Thus Jesus teaches us that the masterpiece of society is the family: a man and a woman who love each other! This is the masterpiece!”

Throughout the homily he lamented, “young people don’t want to get married,” and the growing “number of separations” in many countries, rooted in “a culture of the provisional … everything is provisional, it seems there is nothing definitive.”

Throughout, he repeated the phrase “bond between man and woman.”

Time, CNN, NBC, the Washington Post, CBS, Politico, Reuters and other major media reported on the homily. But they all picked out only one detail: “Pope Francis Calls for Equal Pay for Women,” was Politico’s headline, and that was typical. Some stories didn’t mention the core message of the homily, that marriage between a man and a woman is central to society.

Francis, at times, seems to invite misinterpretation. His breezy delivery has led to overreactions in the U.S. Most famously, Francis said, referring to priests within the Vatican who might be gay: “If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?”

The media took this as a revolution in church teaching on homosexuality and even marriage. Time magazine described it as the beginning of an “evolving Catholic worldview on civil gay marriage.”

But Francis’ “Who am I to judge?” comments were in the middle of a long answer to a two-part question, at the end of a long interview with reporters aboard a plane. In his more careful moments, the pope has been clear that the church rejects the idea of gay marriage.

He was reflecting common Christian ideas about love and salvation. His remarks rested on an unstated distinction little understood in secular discussions: One can experience same-sex attraction without being in a gay relationship or even wanting one.

This distinction is at the foundation of Francis’ view on the issue. Loving the sinner and hating the sin means embracing, granting equality to and loving all those who experience same-sex attraction, but maintaining millennia-old teachings on marriage and sexuality. This ground on which Francis stands is not ground where many in the American political debate plant their flag.

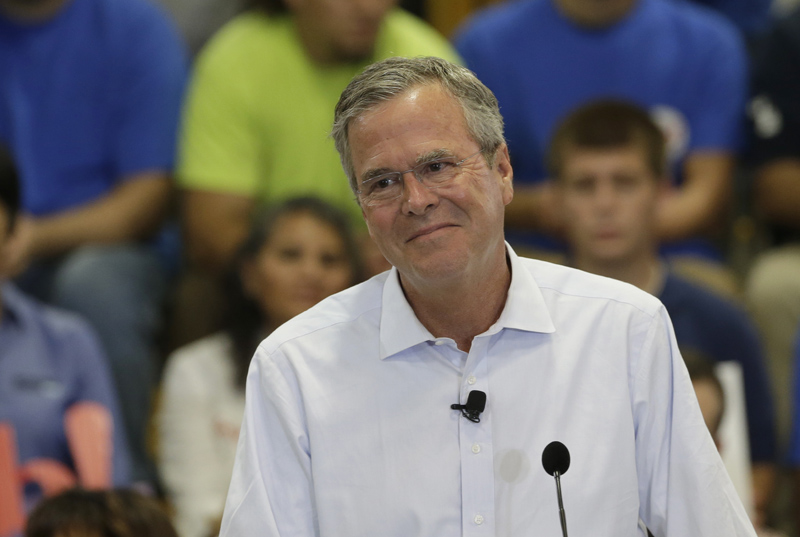

“I think religion ought to be about making us better as people, less about things [that] end up getting into the political realm,” Jeb Bush said.

Presidential politics

Francis’ politics, and his outspokenness, have shaken up the U.S. presidential race. And he’s arriving right in the thick of it.

In past races, Republicans, especially conservative Catholic ones, have used Rome’s positions and arguments as moral ballast for their own arguments. Francis has put Republicans in a tight spot, and some candidates have made mistakes.

Jeb Bush, when asked on Fox News about Francis’ encyclical, Laudato Si, which speaks strongly about climate change and the environmental ravages of an industrial economy, gave an odd answer.

“I think religion ought to be about making us better as people, less about things [that] end up getting into the political realm.”

This is standard liberal rhetoric, calling for a public square scrubbed clean of any religious influence. It is also contrary to the way Bush, a Catholic convert, has spoken in the past.

“As a public leader, one’s faith should guide you,” Bush said in 2009. “In the United States, many people think you need to keep your faith, put it in a security box, if you’re an elected official — put it in a safety deposit box until you finish your service as a public servant and then you can go get it back. I never felt that was appropriate.”

That was when Benedict was Pope.

Rick Santorum, too, has had to criticize his religion’s leader, saying, “The pope should leave science to the scientists.”

Those two likely won’t be the only ones who have to answer for Francis’ statements over the rest of the election cycle. Six of the 17 main contenders for the Republican nomination are Catholic.

The number of homeless around Saint Peter’s square has doubled in the past six months as the Pontiff makes a difference in the lives of so many people. (Eric Vandeville /Sipa USA)

The poor and middle class

The media filter and Francis’s foreign perspective have helped make him the favorite pope of the American Left. But his reputation as a Catholic Bernie Sanders is probably overblown.

Rooney, a Republican appointee, said Francis “is seen in the United States as some sort of a socialist. That’s not true.”

When studying closely how Francis talks about the poor — he is always talking about the poor — one sees that he once again stands on ground that is neither Left nor Right, and not quite in between.

American commentators greeted Francis’ 2013 apostolic exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium, as if it were a companion work to Thomas Piketty’s Capital In the Twenty-First Century, an academic tome warning of ballooning inequality and calling for a global wealth tax.

Much of Francis’ economic writing aligns with Piketty’s perspective and the arguments of the American Left, including laments about structural poverty and unjust distribution of wealth. “Inequality” and “trickle-down” appear repeatedly in Francis’ writings on the economy.

Francis seems to see almost all problems “from the perspective of the poor,” Cunningham said.

But Francis, in Evangelii Gaudium, also curses “irresponsible populism,” echoing the criticism he often leveled at Argentina’s populist Peronist government. It’s telling to see just why inequality bothers Francis.

The pattern: Whether it’s in serving the poor or lecturing the rich, Francis is firmly anti-materialistic, a sensible position for a Jesuit priest who has taken a vow of poverty. Material aid to the poor is primarily a means of spiritually aiding them. A major aim is including them in broader society, mostly for the spiritual benefit of the rich.

“God’s heart has a special place for the poor,” Francis emphasized, “so much so that he himself ‘became poor’ (2 Cor 8:9). The entire history of our redemption is marked by the presence of the poor.”

These Jesuit tones are discordant with the rhetoric of America’s political Left. For them, the existence of the poor is an irredeemable but thoroughly remediable injustice. Francis, on the other hand, “is realistic enough to know that we’re going to have poor people,” as Cunningham puts it.

“Today and always, ‘the poor are the privileged recipients of the Gospel,’ ” Francis writes, quoting Pope Benedict.

Francis’s view of the poor, and the church’s historical view, seems paradoxical at times. Impoverishment is bad, but the poor are a blessing, as long as we welcome them and love them as Jesus did.

A global pastor will spend more time thinking about the poor than any Washington politician. Neither U.S. party talks much about poverty, except in occasional bursts of populism.

Democrats, by autumn 2014, had generally abandoned their talk of inequality, except for minimum-wage advocacy. For both parties, the middle class, the home to swing votes and the class to which most voters believe they belong, matters much more.

Francis, meanwhile, rarely mentions the middle class, and this means the heart of American politics is alien to the pope. This year, the pontiff admitted this oversight. When asked in July by a reporter why he doesn’t talk much about the “working, tax-paying middle class,” Francis granted, “You’re right. It’s an error of mine not to think about this.”

“He may not understand what our middle class is,” Rooney said. This is one area where Rooney hopes Francis can learn from his visit. The foreignness of the middle class to Francis, Rooney said, could contribute to his antipathy toward capitalism.

Rooney said of South American economies, “They don’t exhibit an open style of free enterprise that lets people rise up … They have no middle class.”

This may help explain the pope’s economics, too.

Pope Francis has urged bishops to speak their minds about contentious issues like contraception, gays, marriage and divorce. (AP Photos)

Abortion politics

Americans are divided on the question of abortion. The Catholic Church is not.

“Since the first century the church has affirmed the moral evil of every procured abortion,” the Catechism reads. “This teaching has not changed and remains unchangeable. Direct abortion, that is to say, abortion willed either as an end or a means, is gravely contrary to the moral law.”

This isn’t only a matter of moral guidance for mothers and doctors. It’s a rare commandment to lawmakers. The Catechism continues: “As a consequence of the respect and protection which must be ensured for the unborn child from the moment of conception, the law must provide appropriate penal sanctions for every deliberate violation of the child’s rights.”

Telling governments how to legislate is not something the church does lightly. Even on capital punishment, the church leaves leeway for governments to exercise prudence. On abortion it’s much simpler: it is homicide and must be treated as such.

Pope Francis hasn’t strayed from this line. When asked about abortion in June, Francis said, “Never, never does killing a person resolve a problem. Never.”

As abortion flares up again in the U.S. political debate, pro-lifers are hoping to get a boost from this pontiff. In light of recent undercover videos revealing Planned Parenthood’s role as a supplier of baby parts to biotech companies, some pro-lifers are urging the pope to nudge congressional Republicans to defund the abortion giant.

“Pope Francis can use his moral authority, his clear teaching, and the words of his predecessors in the papacy to compel Congress to end federal support for organizations that further abortion,” wrote conservative activist Neil Siefring. “Indeed, he must.”

Papal experts, however, doubt Francis will get that specific.

“It may be that he’s not going to say too much about abortion, precisely because it’s becoming such a hot-ticket political issue,” Cunningham said. “Rome is kind of sensitive about not involving itself in the internal politics of a country.”

Similarly, Francis’ style, and the Vatican’s recent history, suggests he will explain the importance of marriage between a man and a woman, but not attack the U.S. Supreme Court for ordering all states to perform gay marriages.

On social issues, Rooney expects Francis to “keep it at 30,000 feet. I don’t think he’s going to lecture the United States in the United States about our social policy.”

Issues seen as economic, the pope sees as spiritual. Where Americans talk of the middle class, Francis speaks of the poor. While talk of capitalism may make us think of Main Street and mom and pop, it drives Francis to thoughts of graft and corruption.

This alien perspective will make it easy to misunderstand the pope, and the American press has proven apt to misunderstand him. Some American Catholics also feel the pope misunderstands us. “This is a great opportunity for the pope to learn about America,” Rooney said.

The learning opportunity goes both ways. “It would be a better learning experience for all of us,” Garvey said, “and we would learn more from the Holy Father if we set our pre-existing categories aside and tried to listen to what he has to say.”

This article appears in the Sept. 14 edition of the Washington Examiner magazine.