For years, President Ronald Reagan railed against the Soviet Union. When he entered the White House in 1981, he appeared to double down, and his team of hard-liners fanned the flames.

But in his voice, first lady Nancy Reagan apparently heard something different. While he cursed the red menace, she saw it as his way to bring the Kremlin to the negotiating table and maybe even negotiate an end to the Cold War.

HUGO GURDON: BIDEN BORDER SOLUTIONS LOOK LIKE A BIGGER CRISIS

The late George Shultz, who replaced Al Haig as secretary of state early in the Reagan administration, apparently heard the same thing but always seemed to be elbowed aside and cut off from Reagan by the anti-Soviet hard-liners.

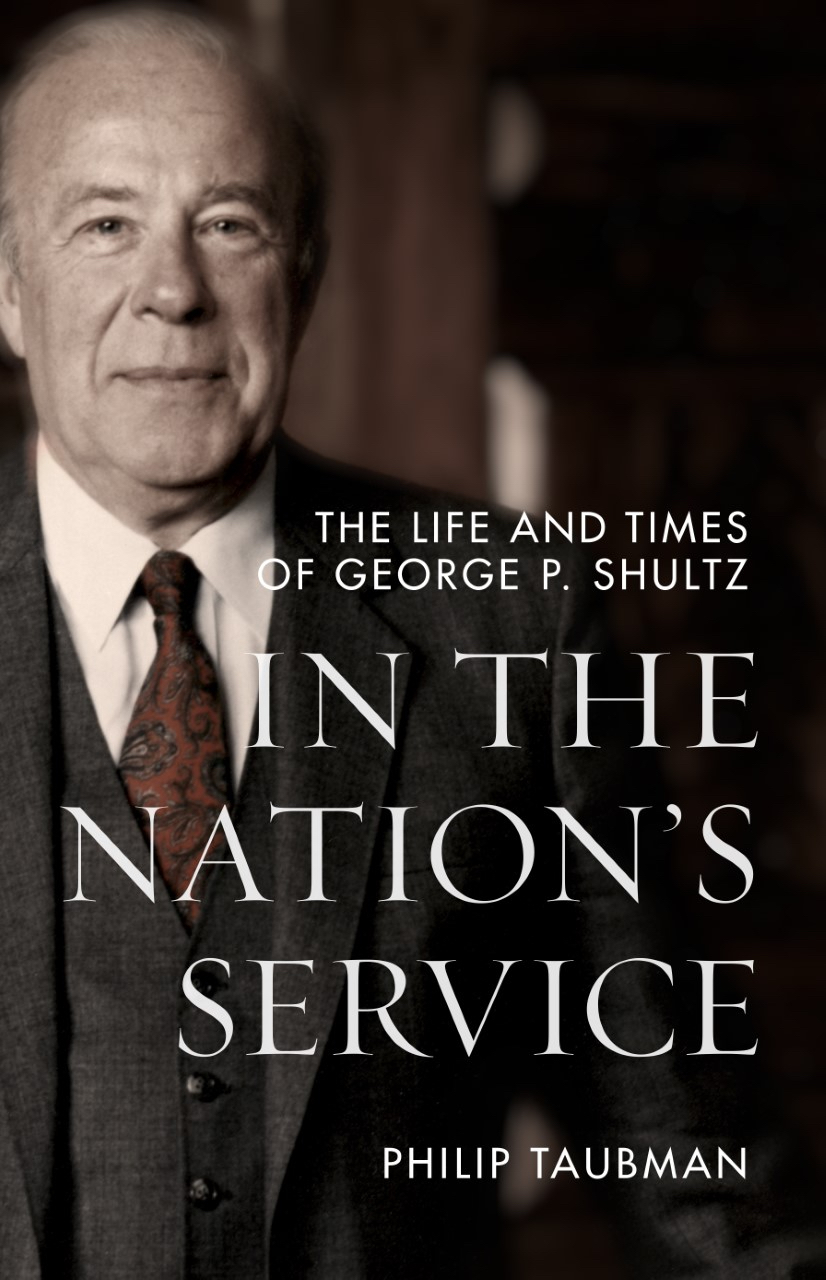

Returning home from Tokyo after just six months on the job, according to a revealing new book from former New York Times diplomatic correspondent Philip Taubman, Shultz felt frustrated that he hadn’t penetrated Reagan’s inner circle and pushed for a path to ending the Cold War.

Soon after, while in his Foggy Bottom office on a Friday in February 1983, the biggest snowstorm since 1922 started, and he rushed home. At the White House, the Reagans were snowed in, blocked from their regular weekends at Camp David, according to Taubman’s book, In The Nation’s Service.

Hoping to broker a breakthrough, on Saturday, Nancy Reagan called the Shultzs’ Bethesda, Maryland, home. “I picked up the phone and it was Nancy Reagan” asking if Shultz and his wife O’Bie could come to dinner that night in the White House’s private residence.

That night, as dinner was served, the Reagans quizzed Shultz about his trip to Asia before the discussion turned to the Soviet Union. Immediately, Shultz realized that he was right that Reagan wanted to develop a relationship with the Kremlin. He even offered to sneak then-Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin in for a chat. Reagan eagerly agreed.

“Shultz for the first time could see that Reagan actually wanted to tamp down the Cold War,” wrote Taubman.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

Taubman’s book is remarkable in many ways. First, it gives Shultz the credit he deserves in guiding Reagan’s foreign policy, especially in ending the Soviet empire, that had been reserved for just Reagan, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, President George H.W. Bush, and his top diplomat James Baker.

Also, it is the first time a biographer has been given so much access to Shultz, who died in 2021 at 100, and a secret diary written by Shultz’s right-hand man, Raymond Seitz. Taubman, who became friendly covering Shultz, said he was asked to write the biography, which turned into a 10-year project.

GET THE INSIDER SCOOP FIRST WITH WASHINGTON SECRETS

And it is the first to show how much Nancy Reagan, and her favorite aide, communications pro Michael Deaver, worked to get the Gipper and Shultz on the same page.

“The melding of minds was precisely the outcome Nancy Reagan wanted” at the snow dinner, said Taubman in his just-released book. She and Deaver “believed Shultz would encourage Reagan to pursue a more pragmatic path with the Soviet Union,” he added.

In the end, they were right. “Absent Shultz’s patience and resilience, it seems unlikely that Reagan could ever have overcome the chaotic conflict within his national security team,” wrote Taubman, concluding, “Were it not for Shultz, it is hard to imagine how the ideological fervor of Reagan’s first years as president could have given way to the pragmatic policies of his second term.”