CORPUS CHRISTI, Texas — Smugglers flying small cocaine-packed airplanes toward the United States from South and Central America might make it to Mexico thinking they went undetected by American forces staked out in international waters trying to interdict them.

But once on the ground in Mexico, from where they hope to smuggle their contraband into the United States, those tiny planes will be greeted by a swarm of Mexican law enforcement. What’s more, they will never know a Department of Homeland Security plane was flying within 100 feet of them, quietly tailing them over the Eastern Pacific or Western Caribbean and then tipping off Mexican authorities.

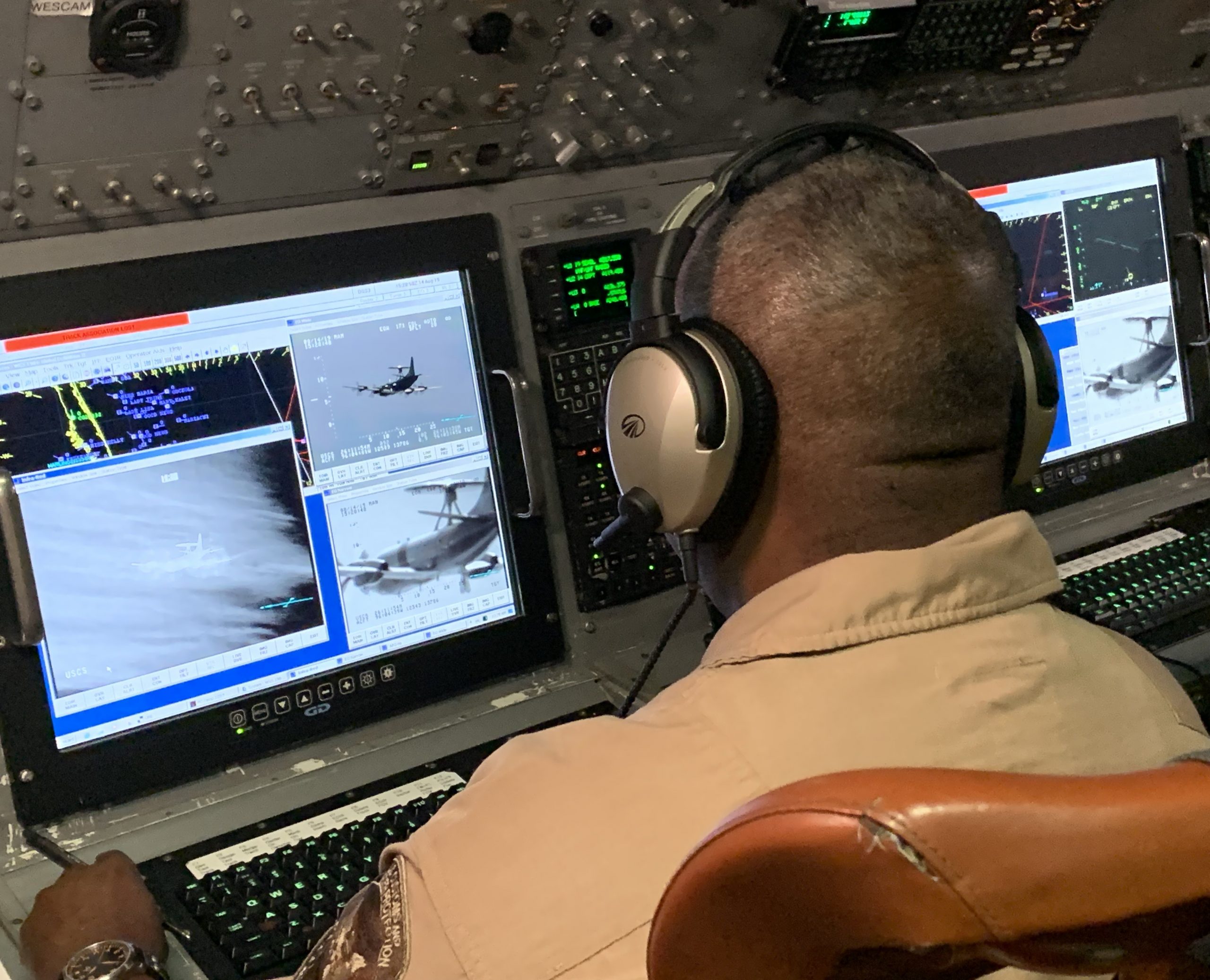

“Even this airplane weighing 100,000 pounds — we can sneak up behind them and they won’t see us. And with the sensors we have on the airplane, a lot of times we don’t even have to get that close,” said Dan Jordan, a supervisory air interdiction agent for U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s Air and Marine Operations.

Jordan, who is based out of Corpus Christi, was standing in the cockpit of the Lockheed P-3 Orion as we soared through the air over the Gulf of Mexico on our way to do a few practice “interceptions” of planes flying as fast as 300 miles an hour.

It was terrifying and thrilling as our 117-foot-long plane came within 50 feet of another just like it, all while zooming through the sky.

Air and Marine Operations air crews such as this one took down $71 million worth of cocaine smuggling operations in the air and sea during an average week last year, but they fly largely unnoticed by the public or the bad guys.

Only 1,800 employees make up CBP’s AMO component, about 10% of the size of Border Patrol’s workforce.

For decades, AMO air crews (previously run by a different federal agency) have made some of the biggest drug hauls by a border agency component, only these take place thousands of miles south of the U.S.-Mexico border.

“The P-3’s job is to catch the smugglers with the cocaine off the coast of South and Central America while the loads are still large and the cocaine is in its purest form. Once it gets to points farther north, up around southern Mexico, the cartels start to add other drugs such as fentanyl or heroin or methamphetamine,” said Jordan. “They break it up into smaller loads. It’s easiest for us to do the most damage to the cartels’ operations down south.”

In the midst of the cocaine epidemic in the 1980s, the then-U.S. Customs Service (under the Department of Treasury) began sending planes down to the waters on either side of Mexico to find both small aircraft and sea vessels attempting to traffic drugs from Colombia and Venezuela.

The need for counter-drug smuggling is even more necessary now as AMO data show its agents led U.S. partners to more cocaine in fiscal 2018 than the average year between 2008 and 2018.

In fiscal 2018, AMO’s 14 P-3 plane crews seized or disrupted 258,296 pounds worth of cocaine, up 57% from the average year over the past decade. By Drug Enforcement Administration values, the crews stopped $3.37 billion worth of cocaine last year and just shy of $25 billion worth of cocaine from being trafficked to the U.S. over the past decade.

AMO relies on a variety of planes for international missions. For these long-distance detachments, it uses any of its 14 P-3s based out of its National Air Security Operations Centers in Corpus Christi and Jacksonville, Florida, because of their long-range abilities as well as air and sea detection capabilities.

At any given time, two to three crews are deployed to Panama, Costa Rica, El Salvador, and other nearby countries. Crew members will head out on deployments every four to six weeks. The week-long trips include five days flying up to 10 hours a day over the open ocean. A crew is comprised of three pilots, two flight engineers, three sensor operators, and three mechanics.

Pilots will fly in a specific “box” area, or they will be given a list of suspicious vessels to track down. Crews may fly 1,000 miles west of Mexico to the Galápagos Islands because smugglers try to avoid detection by going that far out.

“If it’s a smuggler, generally we’ll stay covert the entire time. We’ll come up behind him, get an identification. We’ll look at the numbers printed on the side of the airplane, then we’ll back off and just track them. We’ll trail them all the way to landing. So we’ll let them go wherever they were going. If everything works out right, the wingman law enforcement will be on the ground there waiting for them,” said Jordan.

He said it is easier to arrest people if they land in the U.S., but they go to Mexico more often and Mexican officials cannot always respond in time. AMO works with the Mexican government to continue getting information about the targets after they enter Mexican airspace and will share that intel with other U.S. agencies in the region.

Interdicting boats can be easier because U.S. partners are often in international waters waiting to respond to calls from AMO. Sea interdictions make up the vast majority of the P-3 crew’s work. The boats typically carry larger loads of drugs than small planes.

“Once we get close, once the other boats are inbound, we get close enough for them to see us, or they see the Coast Guard, they’ll start dumping bales [of cocaine] overboard,” he says. “But while we’re sitting there [in the sky], we have a camera on them the whole time.”

The Coast Guard cutter will seize the drugs, arrest the smugglers, and sink the boat because it cannot tow it back to its base while it is out weeks at a time. The Coast Guard has announced major hauls following returns to port several times this year, all because of the big tip-offs by AMO.

Jordan says the plane may be the face of their operation, but it is the people inside the aircraft that create the success.

“This airplane is pretty old, pretty used. What we have is the finest group of aviators and sensor operators and flight engineers that I’ve ever seen,” Jordan said.