A great alliance is only as strong as the sum and strength of its parts. Unfortunately, while NATO has 29 parts (its member states), the alliance’s combined strength is no longer considerable.

Yes, while smaller nations in the alliance such as the Baltic states and Poland are investing in more capable military forces, many of the alliance’s big players are not. Making matters worse, their weakness is not defined solely by absent military capability, but also by a lack of strategic resolve.

We last saw this on Saturday, when just three of NATO’s most powerful members bombed Bashar Assad’s regime. Although the vast majority of other major NATO members such as Canada, Germany, Italy, and Spain supported the strikes on Assad’s chemical weapons program, they refused to participate.

They refused for two reasons: because participating would have been a stretch for their underfunded and poorly equipped militaries and more importantly, because they didn’t want to upset Russian President Vladimir Putin.

For an alliance which exists primarily to ensure the defense of European territory from Russian aggression, such a lack of resolve is deeply concerning. After all, if allies cannot unify in support of a very limited action to deter the use of chemical weapons; that which is a fundamental challenge to international order in the 21st century, what hope do they have of unifying in contest of a Russian invasion?

Because while the prospect of such an invasion is low, it is far from implausible.

Moreover, it is highly likely that Russia would launch an invasion in such a way that exploited divergences in NATO resolve. Russia could, for example, conduct a slow rolling invasion of the Baltic states that began with covert action and slowly built up to the arrival of armored formations. The Russians would almost certainly use this approach to offer multiple exit causeways for NATO states to avoid escalation.

Russia’s hope would be to split the alliance between those willing to support NATO’s collective defense, and those willing to retreat in fear.

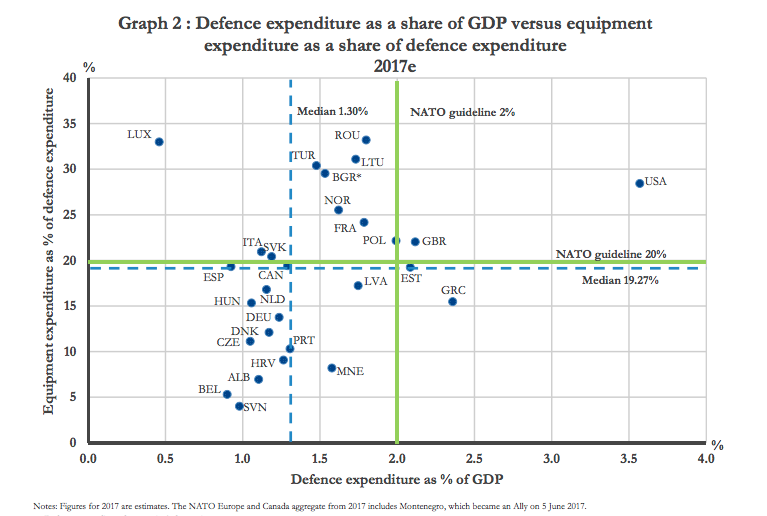

Nevertheless, functional combat capability is another major issue. Consider the following NATO chart, released last month.

The chart shows that only two nations; Britain and the United States spend more than the NATO target of 2 percent+/GDP on defense each year as well as spending more than 20 percent of their total budget on equipment. The equipment proportion matters in that it speaks to capabilities such as jet fighters and tanks.

And while the Baltic states, France (which recently increased spending), Greece, Romania and Poland are close to matching both targets, many NATO members (behind the blue dotted line) are not. The nation that hosts NATO headquarters, Belgium, spends just 6 percent of its paltry defense budget on equipment.

Sadly, major European economic powers such as Germany, Spain and Italy, are ignominiously distinct in their continuing failure to spend more than 1.4 percent of GDP on defense. They are free riders.

So what should the U.S. – and those allies like Britain and France which take defense seriously – do? Two things. First, President Trump should double down condemning NATO states that continue to ignore their responsibilities to the alliance. Trump’s critics like to pretend he is the alliance’s greatest threat, but alongside NATO’s stalwart supporter at the Pentagon, Jim Mattis, Trump is actually NATO’s greatest asset. While committing the U.S. to the alliance, Trump forces its freeloaders to put their money where their mouths are.

Second, balancing strategic depth of logistics with tactical flexibility, the U.S. should relocate its forces in Europe to nations on that continent which are serious about their NATO obligations. If war comes, we must be ready to fight with those who are willing to fight with us.

Ultimately, however, we cannot sit idle. NATO is crumbling and amid Russia’s growing threat, and it must urgently be fixed.