NAVAL AIR STATION KEY WEST, Florida — President Trump is hoping to burnish his legacy as a drug-fighting president and save more lives in the process.

In an effort to make permanent an enhanced hemispheric drug fight started in April, Trump sent his defense secretary to the southernmost point of the continental United States Wednesday to view the Defense Department’s counter-drug operations center.

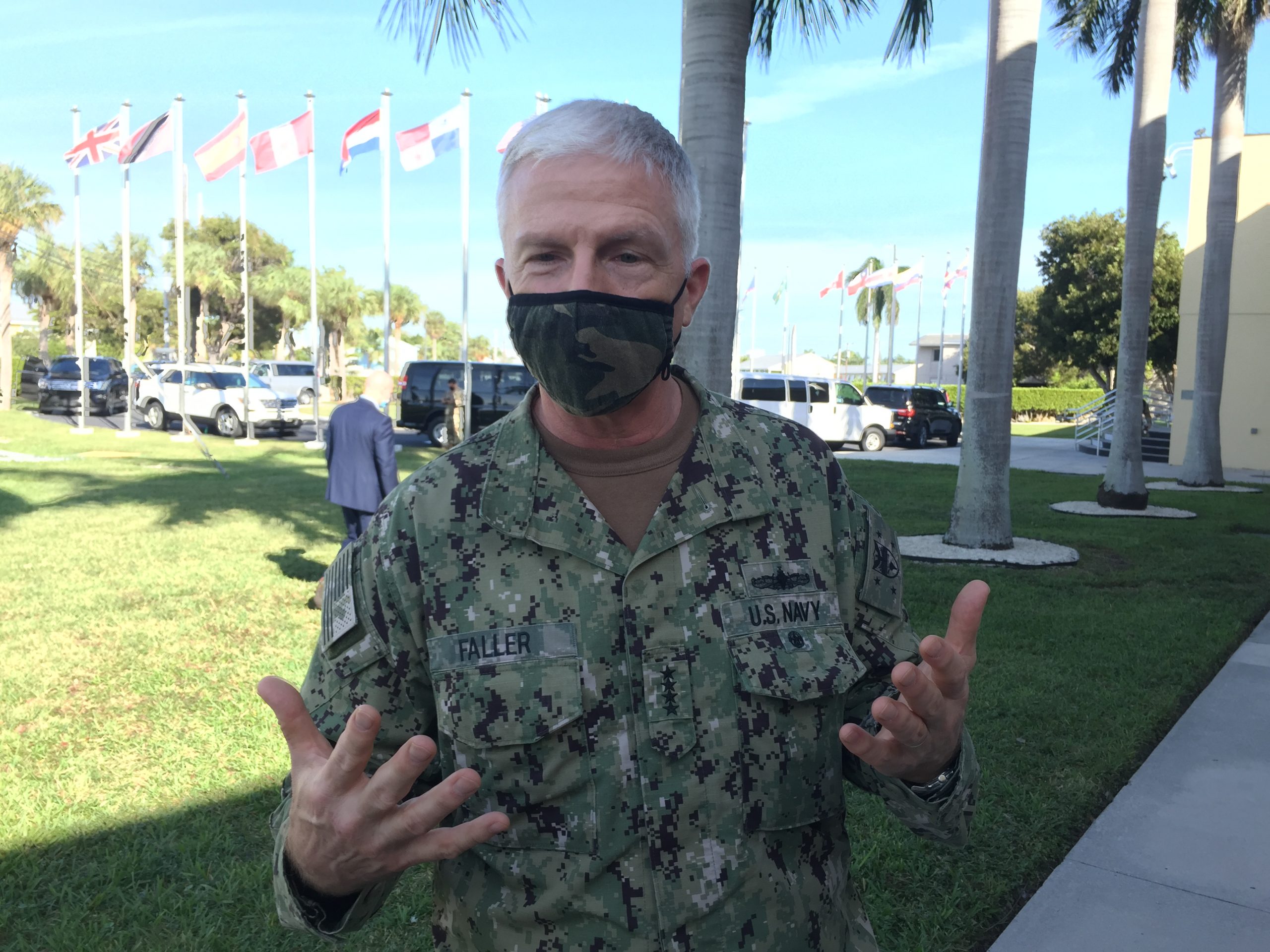

“This is a national security threat,” Adm. Craig Faller, commander of U.S. Southern Command, told the Washington Examiner after a discussion with acting Defense Secretary Chris Miller at the Joint Interagency Task Force South in Key West.

“The operations are making an impact,” he added. “Since the resources were applied in April, we’ve taken a significant amount of drugs off the street, which has saved lives. We’ve also made impacts on these networks.”

Since April, when Trump announced an enhanced counternarcotics effort, more than 216 metric tons of cocaine have been seized.

The reallocated military hardware is directed by the combatant command based in Miami with responsibility for 42 million square miles of sea in the eastern Pacific and Caribbean. That is where drug traffickers actively move cocaine northward toward U.S. shores, stopping along the coast of Central America or island hopping in the Caribbean along the way.

DOD does not have interdiction authority but helps gather information at the Key West clearing house from 21 nations and 16 federal agencies. When suspected boats and aircraft are spotted, JIATF-South passes on the details to the Coast Guard or partner nations who can search and arrest.

“This is an enhanced counternarcotics operation, and we think it ought to be an enduring Op,” Faller said.

Lt. Col. Andrew Ajamian, chief of the strategic initiatives group, explained to the Washington Examiner during a command briefing that the increased assets allow the U.S. to position vessels along known trafficking routes. Additional surveillance aircraft can also zero in on “boxes” of the ocean where drug traffickers are believed to be transiting.

The result has been more interdictions.

Fewer drugs moving through the Americas also helps reduce drug-fueled violence and instability in the region, Southcom public affairs chief, Army Col. Amanda Azubuike told the Washington Examiner.

Faller said that drug flow leads to a vicious cycle.

“Transnational criminal organizations, they are global, and here in the hemisphere, they control territory,” he said. “They deal in narcotics. They deal in human trafficking. They deal in weapons. They’re fueled by corruption, and they undermine the very democratic institutions, which are so important to stable democracy.”

Cocaine was estimated to have killed 14,000 Americans in 2018. In the seven months since Trump’s enhanced counternarcotics efforts, an estimated $5.7 billion in illicit profits have been diverted from criminal organizations.

The wave of crime in drug trafficking waypoints in Central America also contributed to mass migration north to the U.S. border.

“You’ve got instability, crime, mass migration, things being fueled by the profits from illicit narcotics, primarily cocaine, cocaine is the number one moneymaker,” said Ajamian. “It causes people to run to our borders to get away from it.”

The redirected assets included surveillance aircraft such as the P-8 Poseidon, and Navy vessels such as Arleigh Burke-class destroyers to Faller in order to detect more cocaine before it reaches American streets.

Then COVID-19 hit.

Drug traffickers initially recoiled in March and April, then demand rose, and they were back at sea. But the countries of the region that cooperate with the DOD had diverted their attention and assets to the pandemic.

“They just couldn’t support us with how COVID was impacting on their countries at the time,” said Ajamian. “Had we not had those assets, we would not be as successful as we have in the last six months.”

Still, Miller and Faller discussed making the resources permanent, a tough sell for a command far from great power competitors China and Russia and remaining deployed American troops in Afghanistan and Iraq.

“There are challenges right here at home, and they directly impact the U.S.,” said Azubuike.

“What happens is people don’t see a war going on down here,” she added. “When you see the Department of Defense, that’s what they think of, right? It’s a different kind of war.”