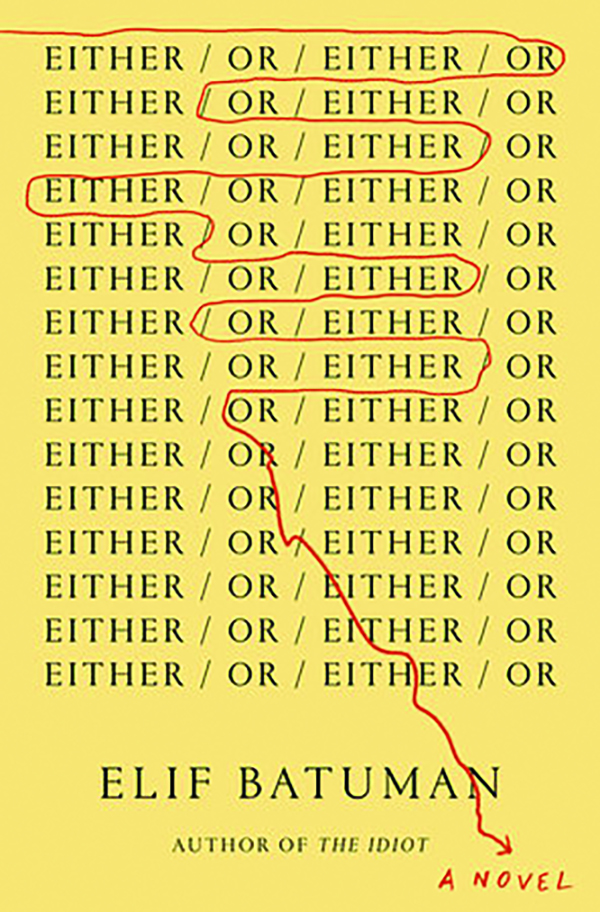

Elif Batuman’s new novel Either/Or forms, with her earlier The Idiot, a brilliant and deft epic of intellectual and artistic tragedy, a sort of anti-Kunstlerroman in which a young woman in her first two years as a Harvard undergraduate systematically forgoes her subtle insights and feral good taste for the well-trod, dulling collegiate pastures of sex, drugs, and politics.

The Idiot ends, hilariously, with the narrator-protagonist Selin’s comment about her freshman year: “I hadn’t learned anything at all.” This clever, self-deprecating attitude, ultimately just a little bit too pessimistic, is left behind in Selin’s sophomore year in Either/Or, which closes: “Was this the decisive moment of my life? It felt as if the gap that had dogged me all my days was knitting together before my eyes — so that, from this point on, my life would be as coherent and meaningful as my favorite books. At the same time, I had a powerful sense of having escaped something, of having finally stepped outside the script.”

The drooping loss of self-awareness is itself a sharp incision from Batuman. Selin in fact spends the whole novel acclimating herself to the social and especially sexual scripts of the world, aided by pharmaceuticals she’s been prescribed for a depression apparently emerging out of the unrequited love she developed in her freshman year. Either/Or dramatizes the way an agile young mind can seem to go limp in trading love for sex, friendship for socialization, art for culture, and thought for commentary.

The dark nimbostratus of sex and politics appears quickly in Selin’s narration. The very first paragraph, describing the dorm to which she and a roommate have been assigned, has four sentences, mostly describing other dorms, “where young men had lived in ancient times with their servants” (third sentence) and “where people had lived with their servants” (fourth sentence). A few pages in, one friend asks Selin, “Did anything happen?” Meaning: Did you lose your virginity? The status of political and sexual awareness as incessant drones that undermine literary goals is established early, as a matter of style before a matter of substance.

The book is organized into four parts, “September 1996,” “The Rest of the Fall Semester,” “Spring Semester,” and “Summer,” with the first part divided into weeks and the others divided into months. Near the beginning, the storm has not yet broken, and we’re still treated to moments of insight and curiosity from the narrator, such as a small debate with her friend Svetlana about the “arbitrary” organization of Harvard’s course catalog, which cleverly also serves as a comment on Either/Or’s own slightly slapdash temporal organization. Selin opens the catalog to “a random page” and sees a class on chance. This aleatory theme is teased, and indeed randomness turns out to be the topic of the senior thesis of Ivan, Selin’s mathematician love interest from The Idiot.

Just as The Idiot takes its name from a novel by Dostoevsky, Either/Or is named after a tract by Soren Kierkegaard. Kierkegaard’s is a complicated book about the choice between a life bound by ethical rules and a life unbound by them, dedicated to having pleasurable and interesting subjective experiences — the “aesthetic life.” Selin and Svetlana take themselves to embody the “aesthetic” and “ethical” lives, respectively, although they don’t really live any differently from each other. This is a great depiction of the straining for identity and differentiation one is bound to see in college sophomores.

Selin sums up, rather beautifully, the conflict between the two views in a reflection on a lecture by a famous philosopher, almost certainly Derek Parfit. Against the philosopher’s concern about measuring the “quality of life” of various people to see whether their lives are, on net, morally worth living, she says: “I wanted to know what it was: the quality of life” — what it is to be alive. To try to recover her own life, which was lost in an obsession or depression over Ivan, Selin follows her friends’ and mother’s suggestions that she “see someone.” She tells this psychiatrist that the whole world is “a huge soul-crushing sex conspiracy that I didn’t know how to be a part of.” The aesthetic and ethical lives are both focused on casual sex — the distinction is a false one. Selin returns to ask for medication and is prescribed Zoloft. Soon she begins enjoying things again.

Batuman has Selin reading Kierkegaard’s Either/Or but missing most of Kierkegaard’s complications and, instead, focusing on a section called “The Seducer’s Diary.” In it, Selin finds echoes of her own experience in The Idiot. The thought that Ivan “had been following a playbook” turns out to be “terrifying but somehow sexually magnetic.” When she confronts him, he emails her a poem far worse than the ones she’s read in Real Change, a newspaper sold by homeless people in the Boston area. Ivan and Kierkegaard’s diarist are “impossibly villainous” — but also apparently the examples par excellence of Selin’s desired aesthetic life. Is she going to be the seduced or the seducer? Will she be taken advantage of or learn to take advantage of others? This rather banal and stupid question forms the basis of the often silly personal transformation effected throughout the rest of the text. Batuman drives it home later by quoting the Eurythmics’s song “Sweet Dreams”: “Some of them want to use you; some of them want to be used by you,” a line that Selin “recognized … to be absolutely true … in a way that would be revealed by adult life, and would be in some ways its defining feature.”

The narrator mourns the fact that her friends have entered romantic relationships, rendering them boring. But really it is sex, entering into the “sex conspiracy,” that makes them, and her, boring. It is like a dingy, flickering fluorescent light turning on as the sun sets. Discussions of art and philosophy make way for an apparently intuitive and instant capacity for judgments of potential and actual partners. Here the quality and substance of the narrator’s thought is some combination of a cheap romance novel and a Buzzfeed article. Selin goes on rants against “nice guys” that seem like training for a career writing for Jezebel. When one such guy cries after being broken up with, she and her friends mock him. Everything is about size and quantity. One girl proudly compares her boyfriend’s penis to a banana. Selin calls another’s “terrifying, curved upward, like a horn.” She talks breathlessly about the sensation of being near men much larger than her. When she brings a man she hooks up with to orgasm, she is surprised by the small, “helpless” amount of ejaculate he produces. She loses her virginity to this guy, who turns out to be a womanizer along the same lines as Ivan. It is a kind of victory for her, though. It seems as though this one, rather than using her, had accepted being used.

It becomes obvious that Selin was right about the sex conspiracy. In her spring semester, we barely hear anything about her classes. The real education at Harvard, she seems by omission to be saying, is elsewhere. It’s at the tiresome parties she describes and in the little playful conversations that happen there. Similarly, her real education in writing is in learning a certain kind of style that she calls (in quotation marks) “witty and irreverent” and that she will use in her job as a travel writer for Let’s Go guidebooks and that also features in an Unofficial Guide to Life at Harvard she reads. Early on in the book, Selin discusses the fact that Ivan had been at Harvard on a scholarship for foreign students, while her parents had paid six figures for her education. She notes that Ivan was, in some sense, “another experience they had paid for me to have.” She transitions to adult life by learning what others value in their experiences and writing about it — by being paid to have experiences rather than paying for them: the aesthetic life as aesthetic livelihood.

The final section of the book, “Summer,” features a kind of sex tour of Turkey, in which the question of just who is taking advantage of whom finds its full but sort of intentionally unlovely expression. Selin is there ostensibly for work for her travel magazine, but the narrative doesn’t describe many of the places she writes for it about, and her real topic of study is what she calls “the human condition,” which she takes to be centered on sex. She falls for some of her paramours, in some cases the more appropriate word might be “assailants,” while not completely enjoying having sex with them and struggling with deeper feelings of superiority to them.

Are these experiences the marrow of life, the quality of life, the human condition that Selin so desperately wants to understand? At times it is difficult to discern her attitude toward them at all. Either/Or has, like The Idiot, been understood as semi-autobiographical. Indeed, the novel itself seems to reference this fact. Selin discusses her “inability” to “disguise the people I knew and turn them into fictional ‘characters.’” But this claimed inability to lie about herself is betrayed in the story itself, especially when it comes to romance and sex: Selin lies to others about her first kiss. During one hookup, she can’t tell if she is faking an orgasm or having a real one.

Batuman might be the smartest novelist writing today, and she’s put plenty of her intelligence into The Idiot and Either/Or. Together, the books show how such a wild and native intelligence begins to be fenced in and put to work, in the processing of the sorts of experiences that a greater culture finds valuable. Batuman’s protagonist Selin, desperately at war with her own strangeness, dives into precisely those pastimes that, once subsumed under her massive powers of understanding and expression, could help her become the sort of normal person who can write for other normal people. The pity is simply that she succeeds.

Oliver Traldi is a graduate student in philosophy at the University of Notre Dame.