Democrats won handily on Tuesday. They took the governor’s mansion in New Jersey, held the governorship in Virginia and scored important victories in down-ballot races. So what should election watchers take away from these results?

(1) Democrats Are (Still) In Good Shape for 2018

Last night, Democrat Ralph Northam beat Republican Ed Gillespie by about nine points in Virginia, a state that Hillary Clinton won by five. In New Jersey, Democrat Phil Murphy beat Republican Kim Guadagno by 13 points, which was similar to Clinton’s 2016 victory in the state. Democrats also won key local and state legislative races, including a number of seats in the Virginia House of Delegates (recounts and the process of counting provisional ballots may delay a final call on control of the chamber). In other words, the blue team outperformed Hillary Clinton by a significant margin—something that they’ll need to do if they want to retake the House and/or Senate in 2018.

Some in the political world will likely spend today arguing that these results aren’t predictive—that Democrats outperformed their baseline in various states, but that these races are primarily local and aren’t informative about the broader national context.

But while gubernatorial results don’t have a great record of predicting midterm results, this sort of argument might miss the forest for the trees: Trump’s approval rating is historically low. Democrats lead by a wide margin in House generic ballot polls. And both the results of special elections and the pace of incumbent Republican retirements suggests that the national political environment is currently very favorable for Democrats.

Moreover, some races that have stronger ties to national politics (e.g. the Virginia House of Delegates) turned out poorly for Republicans. It might be possible to wave off a couple of these indicators. It’s tough to explain away all of them simultaneously.

Obviously conditions could change between now and November 2018. But it’s hard not to see the sum of last night’s results as a confirmation of what we already knew—Democrats are performing well politically.

(2) Don’t Try to Predict Polling Error

In the weeks leading up to the election, Northam held a solid-but-not-safe lead over Gillespie in the polls. That led many to (correctly) consider the possibility that the polls would err and Gillespie would win.

And the polls did err—they understated Northam’s margin.

As I pointed out yesterday, it’s hard to predict if polls are going to miss an election result, and it’s virtually impossible to reliably know ahead of time who they’ll underestimate and by how much. When I looked at nine statewide elections in Virginia over the last decade, Democrats outperformed polls in five of them and Republicans beat the surveys in four.

In other words, poll watching requires some tolerance for uncertainty and a level of self-restraint. Heading into the election, someone from either side could have come up with an interesting, reasonable story about why their preferred candidate would beat the polls. But it’s often best not to get too deep in that type of speculation and simply understand that polling errors (sometimes significant ones) happen.

(3) From a Demographic Perspective, Gillespie Was Too Trump-y

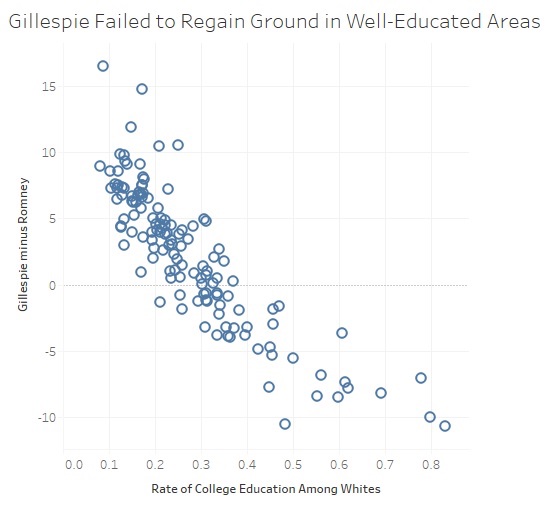

If Gillespie had won, Republicans would have likely heralded his victory as a successful attempt to unite the Trump-skeptical wing of the party and the new converts—that is, to keep Trump’s non-college educated whites in the fold while regaining the support of traditionally Republican upscale whites. That didn’t happen. Have a look:

This graphic shows the difference between Gillespie’s share of the two-party vote and Romney’s, plotted against the rate of college education among whites in each county and independent city. The graphic doesn’t tell the whole story—exit polls, data from voter lists, precinct-level results, and other sources of information will help flesh out the parts of this analysis related to turnout, partisan enthusiasm, and patterns in the non-white vote. And the results might shift slightly as I update the data.

But it shows that Gillespie didn’t come close to having his cake and eating it too. He and Trump both underperformed Romney’s vote share in well-educated areas while driving up the margin where whites were less educated. Northam did very well in areas with large numbers of college-educated whites and Democrats seemed to benefit from high enthusiasm among various key constituencies. In other words, if Republicans want a model of a candidate who can unite Trump voters and Trump-skeptical Republicans, Gillespie was not their man.

(4) Keep An Eye on How the GOP Thinks About This Race

Right now, both parties are trying to work through conflict, bridge internal divides, and create or maintain coalitions that can win elections. Gillespie’s loss may figure into those conversations on the Republican side.

The Republican party is still figuring out how they want to handle the emergence of Donald Trump and Ed Gillespie (who attempted to both hold onto Trump voters while recapturing more traditional parts of the GOP) was, rightly or wrongly, seen as an example of one possible way forward.

Not all Republicans have attempted this sort of synthesis. Some Senate challengers, such as Roy Moore and Kelli Ward, have gone all-in on Trump, while others such as Maine Sen. Susan Collins and Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski have been at times Trump-resistant.

It’ll be interesting to watch what effect, if any, Gillespie’s loss has on these internal conversations about how Trump should, or shouldn’t, change the Republican party.