Last week’s breakthrough in the long, drawn-out U.S.-China trade dispute brought celebrations in the White House and elsewhere. We all should celebrate — but remember the old story about the man who was hitting his head with a hammer and was asked why?

“It feels so good when I stop.”

Ending the “you put a tariff on me and I will raise you one” strategy, one in which most everyone loses, is good news for the long-suffering U.S. manufacturing sector. The fact that holiday shoppers will not be burdened with another round of tariffs on toys, phones, and other consumer goods is good news, too. Add to this the reversal for U.S. agriculture that came when China agreed to increase purchases of soybeans and pork, and you get another shot of good news.

The trade wars with China, Canada, France, Germany, and most of the rest of the developed world were started by the United States. Just as the hammer blows to the head seemed to be hurting a bit, we were assured in July 2018 by the president’s trade adviser Peter Navarro that the pain was not to be severe at all: “We got two economies that add up to around $30 trillion in annual GDP. The amount of trade we’re affecting with the tariffs is a rounding error compared to that.” Navarro went on to suggest that the future payoff would be large.

Well, maybe the amount of trade affected can seem like a rounding error in a gigantic economy, but it does have consequences for plenty of individuals and even entire industries. When viewed in terms of the growth in U.S. exports of goods and services, as shown in the below chart, the effects were undoubtedly hammer blows to some Americans’ livelihoods.

As indicated, U.S. trade was expanding rapidly in early 2018, before the trade wars commenced in full. Growth peaked around December that year, just as the federal government was shuttered for more than a month and tariffs were being raised on Chinese goods. It diminished after that and reached negative territory in the first quarter of 2019.

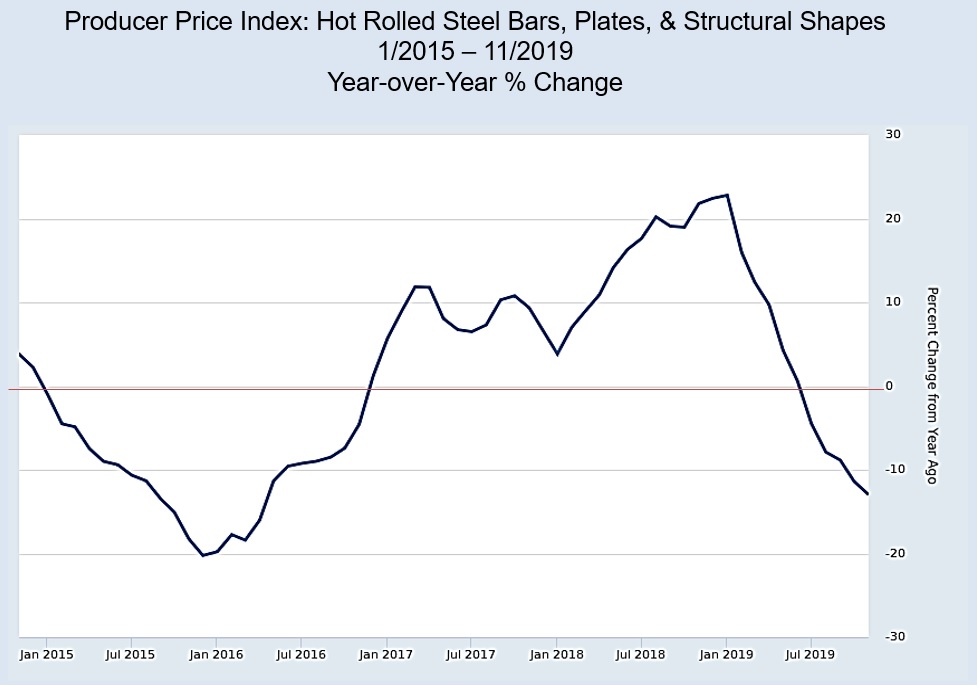

But, wait a minute, what about the industries that were supposed to benefit from the hammer blows to our competitors? What about American steel producers? After all, in May 2018, President Trump imposed a 25% tariff on steel imported from Canada, Mexico, and the European Union. Although later adjusted, and in some cases eliminated, did these tariffs help the U.S. steel industry raise prices?

For a while, but not for long, according to the next chart. As indicated, growth in the Producer Price Index for common steel products accelerated after the tariffs were imposed but turned south in January 2019, around the same time U.S. export growth started falling. After a while, price increases hit zero and then turned into decreases. Like most manufacturing industries, the U.S. steel industry began to suffer from a trade-war damaged, weak world economy.

Not just a rounding error.

Should we celebrate the successful conclusion of the U.S.-China trade negotiations? Of course we should. We are no longer hitting our head with a hammer. And there is still more to celebrate, perhaps. China has agreed to improve protection of intellectual property rights, to increase future purchases of farm and other commodities, to eliminate tariffs on many U.S. products, and to open her doors to more U.S. investment.

In the longer run, the blows to the head may prove to be worth the pain. But the pains experienced were far more severe than those in power suggested they would be.

Bruce Yandle is a contributor to the Washington Examiner’s Beltway Confidential blog. He is a distinguished adjunct fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and dean emeritus of the Clemson University College of Business & Behavioral Science. He developed the “Bootleggers and Baptists” political model.