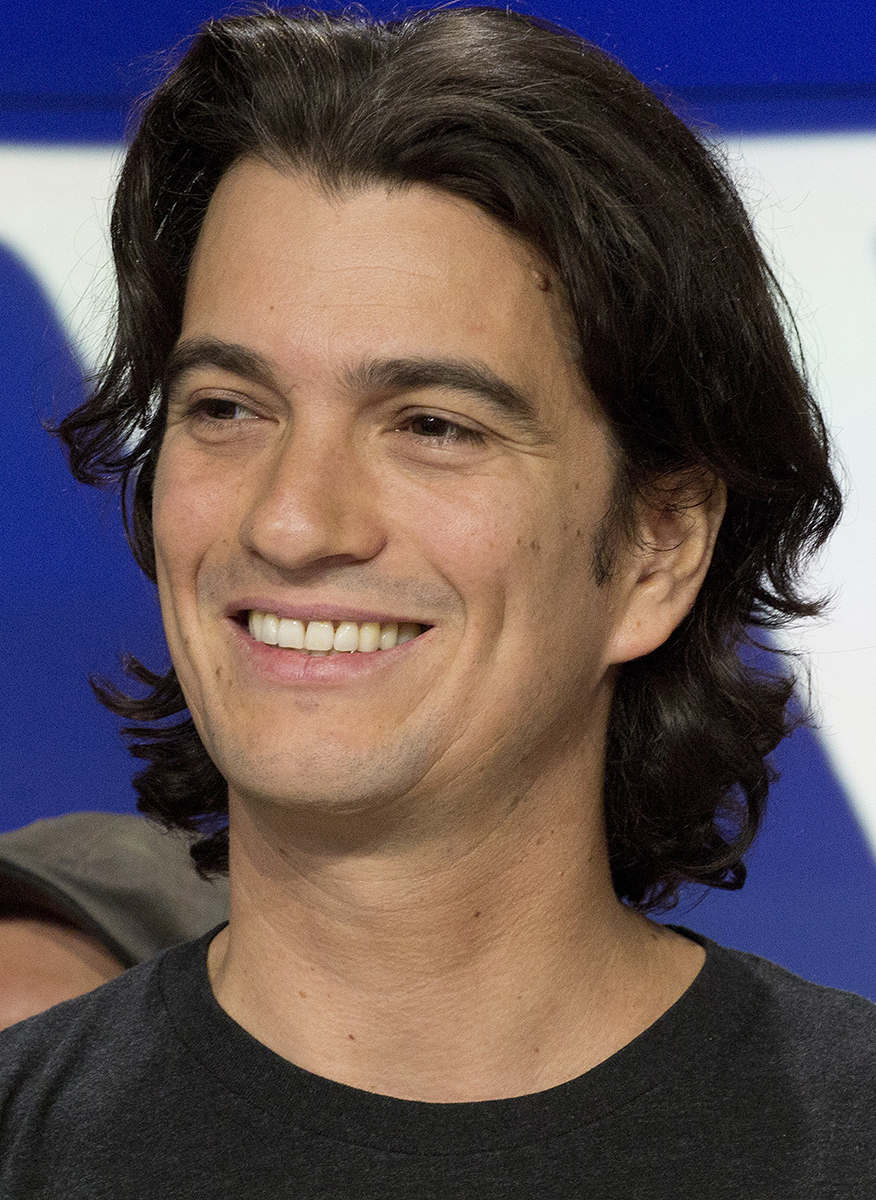

WeWork, at its core, is a real estate company. Its real and most profitable innovation — taking advantage of landowners attempting to rope companies into decades-long leases — is purely logistical, not technological. And yet, the business world has somehow painted WeWork as some Silicon Valley start-up tragedy, with CEO Adam Neumann starring as the villain.

But for all of Neumann’s pot and hubris-fueled faults, he’s not at the core of WeWork’s impending doom. It’s the media myth itself that encouraged investors to overvalue, unwisely, a glorified office space sub-letter.

The crux of WeWork’s profitability is smart. Landlords often issue 7- to 10-year leases for commercial real estate, disproportionately limiting the mobility and potential of startups. WeWork’s sell to investors was obvious: take the 10-year lease to rent out short-term ones to smaller companies hoping to make it into the next year. There’s a profit margin in there, but it’s nothing compared to how a VC class high on their own supply perceived it. Tack on vanity projects such as “WeLive” commuter apartments and “WeGrow” elementary schools, and the divide between returns and actual investments exploded.

Rather than admit that the firm’s conception was misconstrued from the get-go, it’s been too easy for investors to turn the hard-partying but still seemingly competent CEO into the scapegoat. Hence, SoftBank and other multibillion dollar investors have now pushed to oust Neumann as they await an IPO delayed thanks to valid valuation fears. Sure, Neumann may be guilty of hyping his company with a tech brand, but WeWork’s valuation crisis is directly the fault of investors dumb enough to believe him. WeWork embraced the same open-air and wellness-driven workspaces associated with Silicon Valley, but it was never anything more than a real estate company.

Plenty of companies fail to achieve profitability for years, or decades even, and still provide stunning returns in the long run. It took Amazon nine years after its founding — and seven after going public — to turn a profit, and Uber’s still waiting to do so. But both had obvious investments. In Amazon’s case, it was an entire physical system from warehouse to delivery, and in Uber’s it’s the hope of self-driving cars paying off, but even this isn’t a sure bet.

WeWork had no obvious investment with a tech-style ROI, and it still doesn’t. Startups are often willing to pay a double-digit markup percentage for the flexibility of a short-term rental, but the investment ends there.

Neumann’s only crime — well, figuratively speaking — was slapping Silicon Valley-branding onto a glorified office space company, gilded with fruity water and fancy coffee machines. He was right to bet that investors and a sycophantic media class would be dumb enough to believe him.