The next time literary biographer Blake Bailey sits down to write a book, would it be possible for him to select a subject who isn’t a) a disconsolate failure, b) a deeply unhappy husband, c) an awful alcoholic, or d) a paranoid, self-involved ass?

Close to two decades have passed since the publication of Bailey’s 2003 life of novelist Richard Yates, with which the biographer announced himself as our chief chronicler of troubled 20th-century writers. In A Tragic Honesty: The Life and Work of Richard Yates, Bailey affixed his gaze on the massively talented but almost comically unsuccessful author of Revolutionary Road and The Easter Parade. The book remains an exceptional work on an extraordinary subject, but Bailey seems to have taken its success too much to heart.

Perhaps sensing the existence of a cottage industry, Bailey has, since the Yates biography, devoted himself almost exclusively to writing the lives of comparably unhappy or flawed literary giants: to wit, John Cheever (the deeply unhappy husband), Charles Jackson (the awful alcoholic), and now, Philip Roth (the paranoid, self-involved ass).

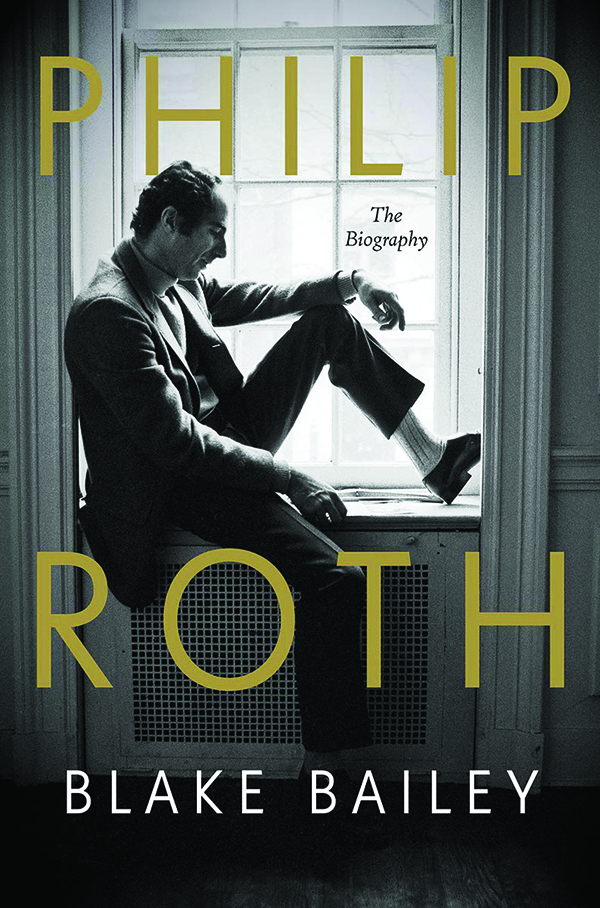

This sounds harsher than it should, and it is in no way an indictment of the literary talent of any of the aforementioned authors. Although Jackson’s record was altogether too thin to merit the Bailey treatment, there is no denying that Cheever is the premier elegist of the suburbs or that Roth, who was born in 1933 and died in 2018, is practically in a class by himself for the depth, variety, and impact of his work. In 27 novels or novellas, Roth ranged over the Jewish experience in America (Goodbye Columbus, the Zuckerman books), the McCarthy period (I Married a Communist), political correctness (The Human Stain), and, of course, the sexual turmoil of the male of the species (Portnoy’s Complaint, My Life as a Man, Sabbath’s Theater, etc.)

I discovered Roth’s work as an adolescent in the mid-1990s, at a time when his status as a giant among men seemed unquestionable. I still remember reading a big-deal Newsweek story in the spring of 1997 that excitedly trumpeted the near-simultaneous arrival of new books by Roth, Norman Mailer, and Saul Bellow. Headline: “The Heavy Hitters Are Up.” Roth’s contribution was the instantly acclaimed, enduringly powerful American Pastoral, which told of the hijacking of a decent man’s life by his violently leftist daughter.

I was hooked. I became a Roth devotee during a period when he seemed to be not only the most vital figure among the old guard — more pungent than Mailer, sprier than Bellow — but also a man capable of dashing off masterpieces at an alarming clip: American Pastoral inaugurated a run of novels that came to include the equally acclaimed I Married a Communist (1998), The Human Stain (2000), The Plot Against America (2004), and Everyman (2006).

I only started to worry around the time Roth published Indignation in 2008. It was a potent work, but by telling of the seemingly preordained downfall of its hapless, blameless protagonist, it evinced a peculiar conception of the world. With its irreproachable hero, whose fate is determined entirely by outside forces, Indignation struck me as the work of a writer with an ax to grind, the literary equivalent of a self-pardon.

Indignation does not play a particularly prominent role in Bailey’s new biography of Roth, but it’s clear that my hunch wasn’t wrong. The very provenance of Bailey’s Philip Roth: The Biography tells us a good deal about how thoroughly Roth bought into the notion that he was, in Newsweek’s parlance, a heavy hitter, a major player, and indeed a shoo-in for the Nobel Prize, were it not for this, that, or the other thing thwarting his ambitions.

In laborious detail, Bailey recounts Roth’s earlier attempts to orchestrate the writing of a biography. Ross Miller had once been the anointed one, but when he disappoints, he’s given the shaft. Hermione Lee, herself the author of a recent doorstop on Tom Stoppard, seems to have agreed in principle but didn’t really have the time. Then, with impeccable credentials, Bailey won the job. Roth had found his Boswell.

As he proved with his earlier volumes, Bailey is an assiduous researcher who has the further gift of spinning many plates at once: He tosses Roth’s life, loves, career moves, disputes, and friendships into the air without ever losing track of any of them. Like a great conductor, or at least a game ringleader, he takes Roth from Newark, New Jersey, the great wellspring of his fiction, to literary fame (Goodbye, Columbus) and fortune (Portnoy’s Complaint) without breaking a sweat. But after a while, an accumulation of sad, sometimes sordid details about Roth’s personal life start to take over: affairs, an ill-advised prescription for the drug Halcion, a nervous breakdown that necessitated hospitalization.

Roth is the victim in some of this, but there are many passages in which he comes across as ungovernably callous. During his divorce from his second wife, the great English actress Claire Bloom, Roth faxed her a list of demands, including that she pay him $150 for each of the “five or six hundred hours” he helped her prepare for acting work, as well as a $62 billion fine for negotiating outside of their prenuptial agreement (this list, Bailey assures us, was meant as a bit of black comedy).

A huge chunk of the book is given over to Roth’s relationship with and estrangement from Bloom. This would be unlikely to displease Roth, who fumed over Bloom’s characterization of him in her sympathetic memoir, Leaving a Doll’s House, which he blamed for denying him the Nobel Prize. In fact, Roth came just short of publishing a “295-rebuttal” to Bloom’s book, but he backed down on the advice of friends. In other words, Roth, similar to a hundred other writers, had a failed marriage that became fodder for the press. The normal reaction is to get over it. But Roth could never get over anything that concerned Philip Roth. Late in life, he arranged for the interviewing of old pals to help create an “audio archive,” fixated on Library of America editions of his works, and spent hours obsessing over a lifetime of personal photos. Roth, as Bailey recounts, even attempted to prevent a writer named Ira Nadel from writing his own Roth biography on the grounds that Roth objected to something else Nadel had written about him in a separate reference book. (Nadel’s biography, unread by me, has been released concurrently with Bailey’s volume, making the whole saga one of this book’s many instances of literary inside baseball.)

Fans of Roth’s fiction will walk away from this treasure chest of his personal shortcomings with a degree of regret. Did he really have to write a nasty letter to the editor objecting to old pal John Updike’s kindly reference to Bloom’s memoir? Did he really have to give the evil eye to Bloom when encountering her by chance years after their divorce? But admirers of Bailey’s protean gifts may have even more to regret in his focus on men of letters who are decidedly not men of character. Would it really be so difficult to write a compelling life of someone more honorable, more humble, more likable — you know, Herman Wouk or Ray Bradbury or even Beverly Cleary?

Peter Tonguette writes for many publications, including the Wall Street Journal, National Review, and Humanities.