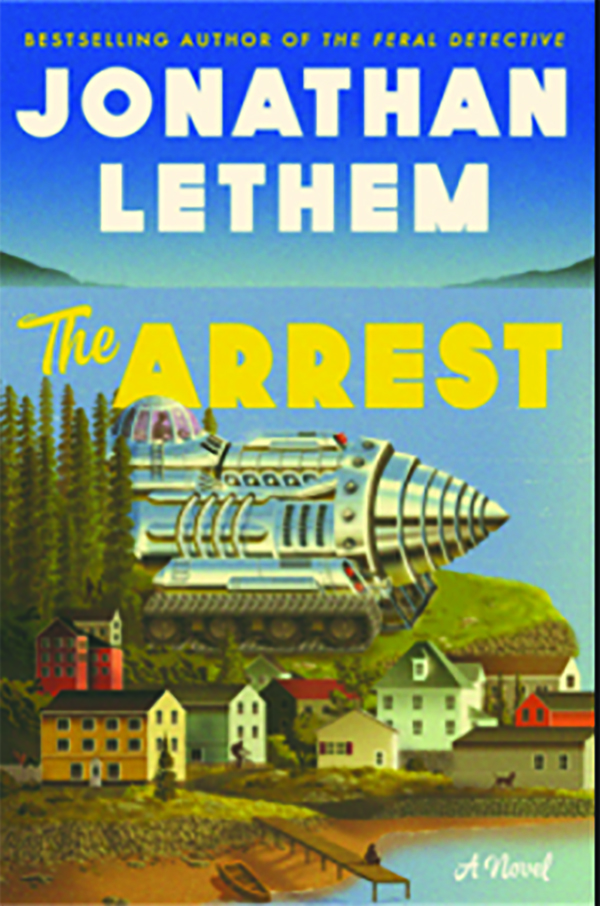

Jonathan Lethem’s new novel, The Arrest, is a post-apocalyptic story about storytelling itself. The Motherless Brooklyn author’s 12th book follows a screenwriter in a small Maine town after the collapse of technological civilization. The novel spends its time exploring Hollywood, genre cliches, and why America is obsessed with tales of the apocalypse. Lethem touches on an interesting question: Why do all our old stories feel stale? The Arrest is a quick and funny read, but its critique of storytelling falls short because it doesn’t take its own questions seriously enough.

The protagonist of The Arrest is Sandy “Journeyman” Duplessis, a former Hollywood screenwriter who finds himself working as a courier in a small Maine fishing village after the collapse of technological civilization in an event referred to as “the arrest.” All technology, from smartphones to guns, stopped working, stranding Journeyman with his sister and her back-to-nature commune, who are perfectly suited to ride out the end of the world.

The story begins with the fantastical reemergence of technology: a massive, nuclear powered “supercar” driven by Peter Todbaum, Journeyman’s old Hollywood writing partner. Todbaum was a big-shot producer who was responsible for Journeyman’s career. He’s a natural bullshitter and a hilarious villain. Todbaum journeyed across the continent in his supercar in order to reunite with Journeyman and his sister, whom Todbaum possibly once raped. The producer is convinced that “the arrest” was connected to a post-apocalyptic film he once tried to make and that the story has spilled out into reality. The town’s Eden slowly becomes undone as the locals gather nightly to hear Todbaum tell stories of his journey.

Lethem’s prose is punchy, and his unique word choice keeps the novel fun to read. A road “slaloms” between towns, Todbaum “futzes” over the controls of his supercar, and when he grunts disapproval, it’s an “oral-flatulent dismissal.” There are times when the book is laugh-out-loud funny, especially with Todbaum, who is odious in the best possible way. His narcissistic proclamations perfectly capture the Hollywood show-business type. In fact, Todbaum is so memorable that he brings into relief just how underdeveloped the other characters are. The novel ostensibly follows Journeyman, his sister, and Todbaum, but the first two are vague and forgettable. The plot drags a bit, but this feels deliberate because the book spends a lot of time examining storytelling itself.

The Arrest is primarily preoccupied with exploring the post-apocalyptic genre. Todbaum is obsessed with creating a movie that combines dystopian and post-apocalyptic themes. In a conversation that feels like a key to the book, he dismisses the idea that these stories are cautionary tales or warnings about possible realities. Instead, he argues, storytellers “want to live there. You can feel it. The characters in the book, they’re always justified, set on a road … The world’s reduced and cleansed, the ambiguity scrubbed out … Postapocalyptic comfort food.” Are tales of the end of civilization secretly pastorals, fantasies in which people are free to live simply, unburdened by the complexities of modern life? Todbaum is the villain, so it would be a mistake to conflate his dialogue with the message of the novel itself, but here, his views are certainly close to Lethem’s own concerns.

One of the fixtures of the post-apocalyptic genre is that small, closely knit bands of people come together to rule themselves. In The Arrest, for instance, the town has meetings in which they debate what to do about Todbaum. Something has gone wrong when the fantasies of ostensibly free societies revolve around people ruling themselves. The novel’s epigraph is a poem that compares America to a cage, and toward the end of the book, Journeyman wonders if people listen to Todbaum’s stories of the outside world simply to understand whether they’re “captives” in the town. This line of thought is not fully developed, so the book has a feeling of being unfinished. It feels like a cop-out when, at the end, the novel proclaims that we need new types of stories. What this proclamation overlooks is that Todbaum’s accusations against the post-apocalyptic genre could be leveled against all stories. All stories must narrow life’s complexity by their very nature. This provides an interesting connection between technology and storytelling that Lethem misses.

At their core, both stories and technology reduce the types of questions a person can ask. Technology is applied science, and science is a form of questioning that is predicated upon limiting the types of questions that can be asked. Science can only ask, “What is the atomic structure of this rock?” by first dispensing with the question, “What is the purpose of this rock?” Stories function in a similar manner. They can only reveal aspects of being human by first limiting the questions an audience can ask. Stories ask us to suspend disbelief. This is a more fundamental request than just asking us to accept the premises of a fictional world. A story about a small town in Maine only works if a reader accepts that it will ignore life in Beijing. Because Lethem fails to acknowledge the way fiction limits, his novel attempts to do too much. It attempts to be both a post-apocalyptic story and a type of literary criticism, but this just ends up being underwhelming.

The Arrest is a genuinely funny book, and fans of Lethem will have fun with it. Yet wider audiences may feel like it’s an unfinished novel. This might be because a story must narrow, and so Lethem’s ruminations on storytelling must happen in a narrow domain. It’s an inward-looking examination of storytelling and genre that misses the big picture.

James McElroy is a novelist and essayist based in New York.