Twenty years ago, Peter Bogdanovich, filmmaker, film scholar, and film enthusiast, introduced modern audiences to Elinor Glyn.

In Bogdanovich’s marvelous 2002 historical drama The Cat’s Meow, several icons of early Hollywood, including Charlie Chaplin, actress Marion Davies, and producer Thomas Ince, are shown converging on the yacht of Davies’s lover, media mogul William Randolph Hearst. There, Hearst, thinking he is offing Chaplin for romancing Davies, mistakenly shoots and kills an innocent Ince.

Strikingly, the whole story — gossipy, irresistible, undoubtedly embellished — is told through the jaundiced, all-seeing, and altogether elegant eyes of a figure far less famous today than any of her fellow passengers: novelist, screenwriter, and waggish wit Glyn, played in the film by a raven-haired Joanna Lumley of Absolutely Fabulous, whose manner was wonderfully imperious, icy, and grand. As Bogdanovich surely knew, Glyn, whose novels and screenplays ushered in a new era of sexual candor, was the perfect one to tell the tale: She would be shocked by nothing, and observant of everything.

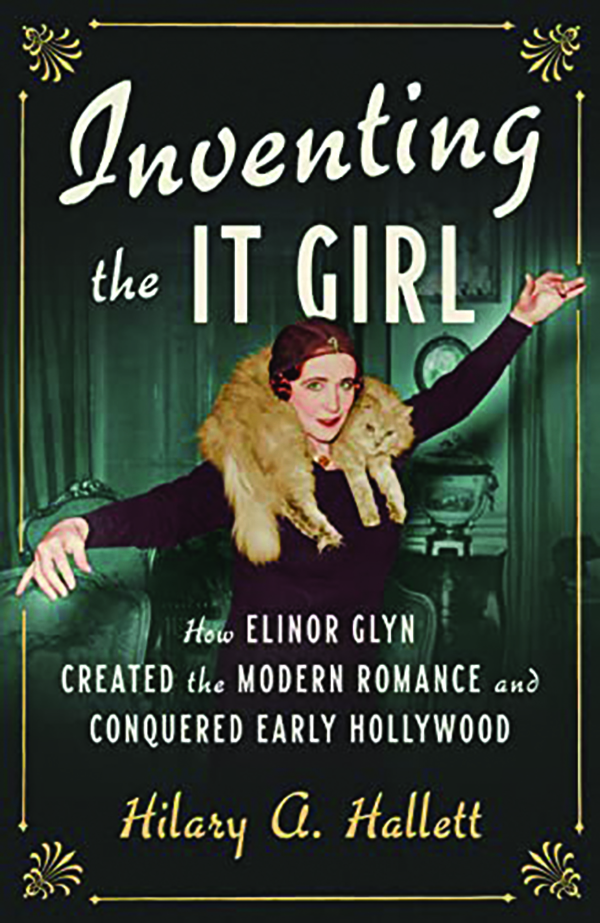

Those intrigued by this once-ubiquitous, now long-forgotten figure are sure to devour Hilary Hallett’s Inventing the It Girl, a lavishly detailed new biography of the British writer whose accomplishments include dreaming up the term “It” as a name for that exceptional, undefinable quality that emits from certain stars, most notably the original “It girl,” silent-screen goddess Clara Bow, who starred in a 1927 film based on Glyn’s novella It.

As it happens, Hallett doesn’t put much credence in the rumors of Hearst murdering Ince — she concedes that Glyn, whom she calls by her lifelong nickname of Nell, was on Hearst’s yacht but asserts that “the idea that Hearst shot Ince defies both common sense and all of the known facts” — but there are enough fascinating details, incidents, and controversies about her life that are unassailable to make this book as engaging to read as The Cat’s Meow was to watch.

In her works, words, and deeds, Glyn acknowledged the existence of lust in the fairer sex and celebrated its consummation. In other words, she wrote what would today be classified as romance novels, including the hugely popular tale of an older woman, a queen in fact, who pursues an amorous relationship with a young fellow, Three Weeks, which, upon its publication in 1907, scandalized many readers and seduced many more. A famous piece of doggerel, possibly the work of no less than George Bernard Shaw, Hallett says, captured Glyn’s role in encouraging vice in print and on screen: “Would you like to sin / With Elinor Glyn / On a tiger skin, / Or would you prefer / To err with her / On some other fur?”

Although the overripe plots and florid language of Glyn’s novels make them unlikely to land on contemporary reading lists — “She purred as a tiger might have done, while she undulated like a snake,” reads one representative passage from Three Weeks — Hallett persuasively makes the case for Glyn as a breaker of barriers and establisher of cliches. “Smoldering looks, long kisses, lingering caresses, and embraces that contain a show of force became the stock-in-trade of the romance, whatever medium,” Hallett writes. “She conceived all of these.”

Of course, like all revolutionaries, her life began innocently enough. The daughter of Douglas and Elinor Sutherland, young Elinor was born in 1864 in the Channel Islands, but, after the premature death of her father, experienced a nomadic, though well-off, childhood in the care of her mother and stepfather, David Kennedy. Like Susan Sontag, who also lost her father and was saddled with a stepfather, Glyn steeled herself from the world with books, immersing herself in tomes that persuaded her that she was “secretly in rebellion against the whole series of Lawgivers from Moses to Zeus to Queen Victoria, and my stepfather, Mr. Kennedy.” In her 1905 novel The Vicissitudes of Evangeline, Glyn presents a heroine whose sense of herself is that of an “adventuress” — “I read in a book all about it; it is being nice looking and having nothing to live on, and getting a pleasant time out of life — and I intend to do that!” Evangeline says, though, in reality, Glyn honored some societal conventions: She married an aristocratic type, Clayton Glyn Jr., with whom she had two daughters, Margot and Juliet, and, throughout her life, was known for her manners. Decades later, in Hollywood, a waitress who served Glyn exclaimed: “Of all the people I ever waited on Mrs. Glyn was the nicest and kindest and most considerate. I never knew her to be cross — not even at breakfast.”

Yet, in her imagination, Elinor was unbowed: In presenting a heroine seeking to satisfy her libidinal urges in Three Women, she won fans in high places, including two Russian grand duchesses who beckoned Glyn to the Romanov Court, and the Duchess of Edinburgh, who “admitted to Nell how much she had enjoyed reading the novel in bed.”

Naturally, Hollywood, then operating without the restraints of the Production Code, seized on Glyn’s gifts (and name recognition) in the 1920s. In an industry already full of female writers, studio bosses anointed Glyn the First Lady of the risque and racy. She wrote The Great Moment, starring Gloria Swanson, about which the Los Angeles Times judged: “Nothing more sensational has been seen on the screen, even in the most horrible moments of the serials,” apparently not a compliment. Even so, the public ate it up. She tutored Rudolph Valentino, star of that classic piece of romantic tripe, The Sheik, and an adaptation of Glyn’s own Beyond the Rocks, even ghostwriting a Photoplay article in which she gives the famous lover these words: “Women don’t want caveman techniques but finesse. It is only after you have won her love that you dare be master.” Later, Glyn was paired with the unrefined but enchanting Clara Bow, whose takeover of the American popular imagination the writer helped engineer. “Her large, lovely eyes flashed with life, and her tiny figure seemed all-alive with desire to go,” said Glyn, for whom there could be no greater praise.

The book creeps along as it dives into the minutiae of the publishing and movie industries as they existed 100 years ago, but the subject remains a vital force. Although Glyn, who died in 1943, was not an unreconstructed libertine (she was a teetotaler and, oddly, cast herself as a voice for screen morality around the time of the Fatty Arbuckle scandal), and certainly not without flaws (she seems to have absorbed the antisemitism of her class and era), she nonetheless emerges by and large as a positive, life-giving force. “She had done her part to let loose the genie of women’s sexual liberation,” Hallett writes, “and it would not be stuffed back into the bottle again.”

H.L. Mencken said that puritanism was an expression of the worry of scolds that “someone, somewhere may be happy,” and by that reckoning, the puritans could surely have found no one happier than Elinor Glyn.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.