Greece on Monday completed its European Union bailout program. Unfortunately, the Mediterranean nation can’t expect smooth economic waters ahead.

On paper, things look more optimistic. The just concluded, three-year, nearly $71 billion, loan-plus-reform package means that Greece will now borrow money at international market rates. Part of a $330 billion total bailout, Greece is supposed to pay back the loans over the coming decades.

But that’s where the good news ends.

First off, much to the chagrin of the German taxpayers who provided it, many of Greece’s loans are likely to be written off. The simple issue is that it is extremely difficult to see how Greece can generate economic growth anywhere near the level it would need to pay off those loans in full. One standout concern here is that Greece’s 180 percent debt-to-GDP ratio has stabilized, but remains astronomically high. Another issue: while Greece has introduced some pension reforms and spending cuts, its outlays continue to be excessive.

But Greece’s primary issue is that its economy remains far too reliant on the bloated public sector. Using government jobs as a means of economic investment, the Greek economy is both inefficient and unproductive. At the same time, too many of Greece’s private sector industries remain afflicted by massive reams of red tape and bureaucratic inertia.

That’s not all. Referencing IMF estimates, Bloomberg suggests that Greece’s shadow economy (that beyond the reach of tax collectors and the law) is now a whopping 27 percent. Other statistics are equally unimpressive: Greece’s unemployment rate is just shy of 20 percent and its youth unemployment rate is falling, but still at 40 percent (thanks, socialism).

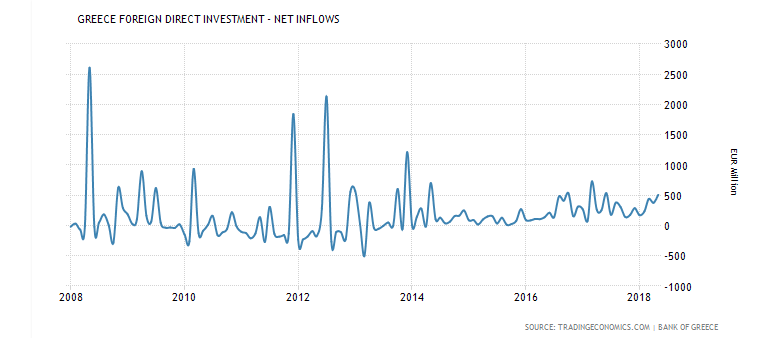

Also concerning? As the chart below shows, the trend lines for foreign investment are far from inspiring. That investment is crucial towards Greece’s improved investment, infrastructure, and productivity, and as a marker of market confidence in Greece’s medium-to-long-term growth prospects.

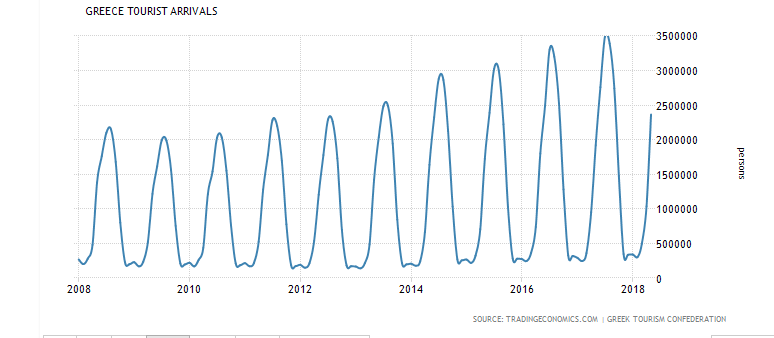

But at least one thing is moving in the right direction: A crucial sector of the Greek economy, tourism, is climbing steadily.

Nevertheless, the long term picture remains somewhat bleak. Greece has largely chosen discretionary reforms over a structural free marketization of its economy. It also remains plagued by a Euro currency that preferences bigger economies such as France and Germany. All this means that when the next global recession comes, the Greeks face new suffering.