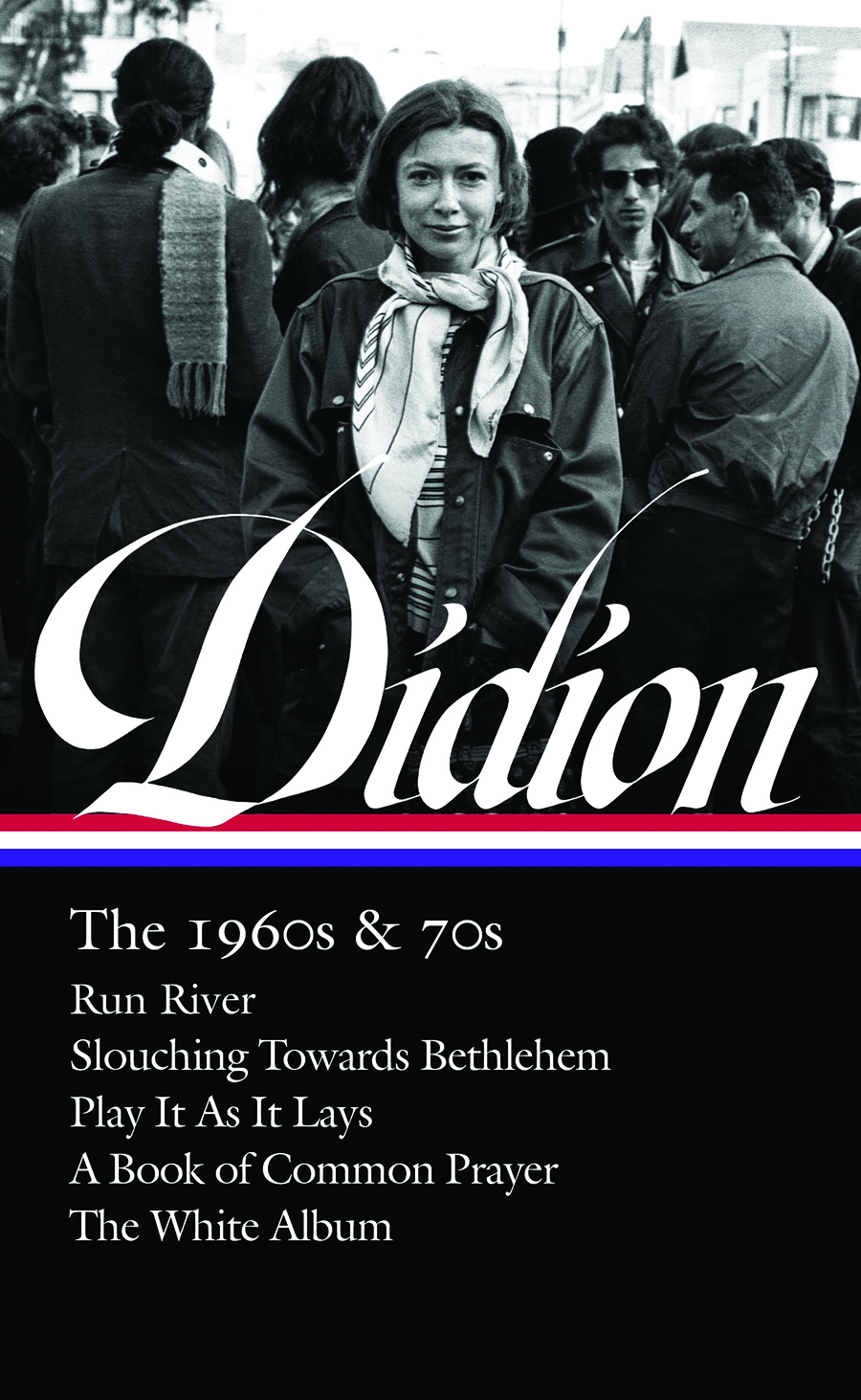

The cover image of Joan Didion: The 1960s and 70s, a new anthology from the Library of America, is a photograph of a cluster of people on the street in hippie-era San Francisco. Most face away from the camera, looking at something out of frame. Didion stands apart; back to the crowd, she looks directly at the viewer, smiling slightly. Over her workaday reporter attire, she’s wound a chic scarf.

The picture almost perfectly captures Didion’s enduring appeal as a writer, the flinty essayist observing the zeitgeist at a deliberate remove, as well as the Didion brand: the aloof, sunglasses-wearing “Literary Sad Woman” whose image has graced many a tote bag.

This new anthology, published in November, gives Library of America’s stamp of approval to a corpus of essays and journalism already well enshrined in the literary nonfiction canon, as well as three novels: Run, River (1963), Play It as It Lays (1970), and A Book of Common Prayer (1977). For much of this period, Didion’s main muse was her home state, and many of the selections concern California: as a place, as an idea, and as the mecca of a counterculture that fascinated and unsettled Didion.

Like Orwell, Arendt, or V.S. and Shiva Naipaul, Didion was keen to be someone who saw clearly, alert to but unclouded by cultural and ideological vogues. Her personality — shy, neurotic, a delicate sort of brilliant, craving of control — was inevitably in conflict with the disorder and breakdown of the ’60s and ’70s.

Sometimes Didion’s efforts to dramatize that conflict strain credulity. Did a psychiatrist really write, in the lengthy clinical report Didion quotes in “The White Album,” that she suffers from a worldview “of people [as] moved by strange, conflicted, poorly comprehended, and, above all, devious motivations which commit them inevitably to conflict and failure”? (If only my psychoanalyst wrote anything so interesting about me.) Was her anxiety really so debilitating that she drove across the Carquinez Bridge with her eyes closed? (And wouldn’t that be more stressful?)

Didion remains sui generis as a prose stylist. She has a knack for the accumulation of detail and the slow reveal, and her best passages have satisfying precision and authority:

There’s also a lot of affectation and self-indulgence: stilted formality, redundancy, repetition, and coy vagueness, though, of course these tics are what make Didion, Didion. The New Journalism era tolerated “voice” and word counts to a degree unthinkable in today’s media industry. Modern editors would be less tolerant of her idiosyncrasies.

In tone and theme, too, Didion sometimes gets close to self-parody. She presents herself as scornful of sentimentality but wrings mood from every occurrence or image. (“There is something uneasy in the Los Angeles air this afternoon, some unnatural stillness, some tension.”) This is the tone that once led Barbara Grizzuti Harrison to liken Didion to a “neurasthenic Cher”: The storm is always on the horizon; the apocalypse is always just around the corner. In 2014, Heather Havrilesky compared Didion with her less self-serious contemporary, Nora Ephron:

As Harrison argued, Didion’s fatalism often feels like preemptive excuse-making for her apathy. But history has been favorable to Didion. Her suspicion of the counterculture was mostly correct.

There’s some irony to the cult of Didion. The very qualities her fans admire in her writing from the ’60s and ’70s, her aloofness, her skepticism, would not necessarily endear her to the same readers today. Her essay “The Women’s Movement,” for example, makes clear she did not consider herself a member.

The disturbing image most people remember from “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” Didion’s dispatch from Haight-Ashbury, is the 5-year-old girl on LSD. Would these readers react with similar unease if Didion depicted, with ironic detachment, a parent pressuring their 5-year-old into a dubious gender transition? Or would they cheerlead the final victory of the bourgeois radicalism whose rise Didion chronicled with such ambivalence and foreboding?

J. Oliver Conroy’s writing has been published in the Guardian, New York, the Spectator, the New Criterion, and other publications.