Welcome to Byron York’s Daily Memo newsletter.

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up here to receive the newsletter.

A PRESIDENT, A BIG INVESTIGATION, AND THE PARDON POWER. Many Democrats, along with some in the press and a few Republicans, have expressed outrage at President Trump’s commutation of political operative Roger Stone’s sentence for lying to Congress and witness tampering.

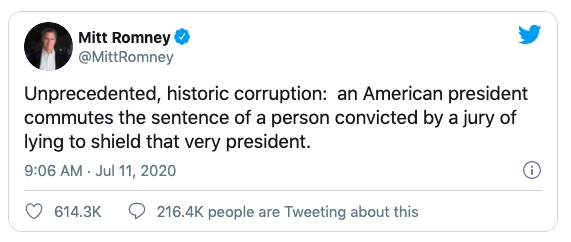

GOP Senator Mitt Romney, the only senator ever to vote to remove a president of his party, was particularly outraged. On Saturday, Romney tweeted of the commutation: “Unprecedented, historic corruption: an American president commutes the sentence of a person convicted by a jury of lying to shield that very president.”

“Unprecedented”? Who is Romney kidding? Put aside your opinion of whether Trump acted properly or improperly in commuting Stone’s sentence — an action comparable to President George W. Bush’s decision to commute the sentence of top White House aide Lewis Libby, convicted of perjury and obstruction of justice in the CIA leak affair. (The 2007 Mitt Romney defended that commutation as “reasonable.”)

Subscribe today to the Washington Examiner magazine that will keep you up to date with what’s going on in Washington. SUBSCRIBE NOW: Just $1.00 an issue!

But put that aside. Is what Trump did “unprecedented” because Stone was “lying to shield” Trump? Perhaps Romney has forgotten the way-back time of 2001, when President Bill Clinton, on his last day in office, pardoned his old Arkansas business partner Susan McDougal. In 1996, McDougal was convicted of fraud and other felonies in connection with the Whitewater business enterprise that she and her husband entered into with Bill and Hillary Clinton. President Clinton testified at the trial.

The Whitewater independent counsel, Kenneth Starr, raised the possibility of a reduced sentence for McDougal if she testified against the Clintons. Specifically, Starr’s prosecutors asked McDougal, “To your knowledge, did William Jefferson Clinton testify truthfully during the course of your trial?”

McDougal refused to answer. She demanded that Starr resign. And then she stayed silent. A federal judge jailed her for 18 months for contempt of court. Starr later charged her with criminal contempt, a case which ended with a hung jury. But through it all, McDougal steadfastly refused to say whether Clinton had testified truthfully at her trial.

Then, on January 20, 2001, as he left the White House, Clinton pardoned McDougal. By the next year, she had written a memoir, The Woman Who Wouldn’t Talk: Why I Refused to Testify Against the Clintons and What I Learned in Jail. And then, in 2004, Hollywood made her one of the stars of the documentary film “The Hunting of the President: The Ten-Year Campaign to Destroy Bill Clinton.” The former president attended the film’s premiere in New York, where he told the audience of his deep admiration for the woman who refused to testify about him.

“He [Clinton] said, there’s an American hero in the audience, and I’d like to recognize them,” McDougal recalled of the evening. “And then he said, ‘Susan McDougal.’ And I — I couldn’t believe it.” Bill Clinton did a lot to recognize and reward the woman who refused to tell a grand jury whether he, Clinton, testified truthfully.

Of course, Clinton pardoned others, too. As Andrew McCarthy has noted, Clinton “pardoned his own brother for felony distribution of cocaine…And three others convicted in independent counsel Ken Starr’s probe. And Marc Rich, in what was a straight-up political payoff. And his CIA director. And his HUD secretary. And eight people convicted in an investigation of his Agriculture Department.” Clinton acted in large part because he believed the investigations into his administration and White House had been unfair.

Does that sound familiar? Rather than being “unprecedented,” President Trump’s commutation of the Stone sentence fits into a pattern of presidents granting clemency to those caught up in investigations targeting their administrations. (Clinton’s predecessor, George H.W. Bush, did it too; in late 1992 he pardoned six figures who had been convicted or pleaded guilty in the Iran-Contra affair.)

None of that makes what Trump did right or wrong. But people around Washington should stop acting like it’s something they’ve never seen before.