The promotions of eight white men to leadership posts within the U.S. Border Patrol in May left some agents feeling as if the federal organization is failing to address diversity in its ranks.

At the onset of President Joe Biden’s administration, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the nation’s largest law enforcement agency and overseer of the Border Patrol, moved to fill vacancies at regional offices primarily along the northern and coastal borders that have been occupied by temporary “acting” officials. Border Patrol is comprised of nearly 20,000 people, of which Hispanics make up approximately 51%. Just 5% of all agents are women. Agents work most often with Latin migrants who have illegally crossed the U.S.-Mexico border and are intercepted during that process.

But the diversity in the Border Patrol’s workforce was not reflected in recent promotions, for reasons that current and former officials, including the head of the Border Patrol, spoke with the Washington Examiner about at length.

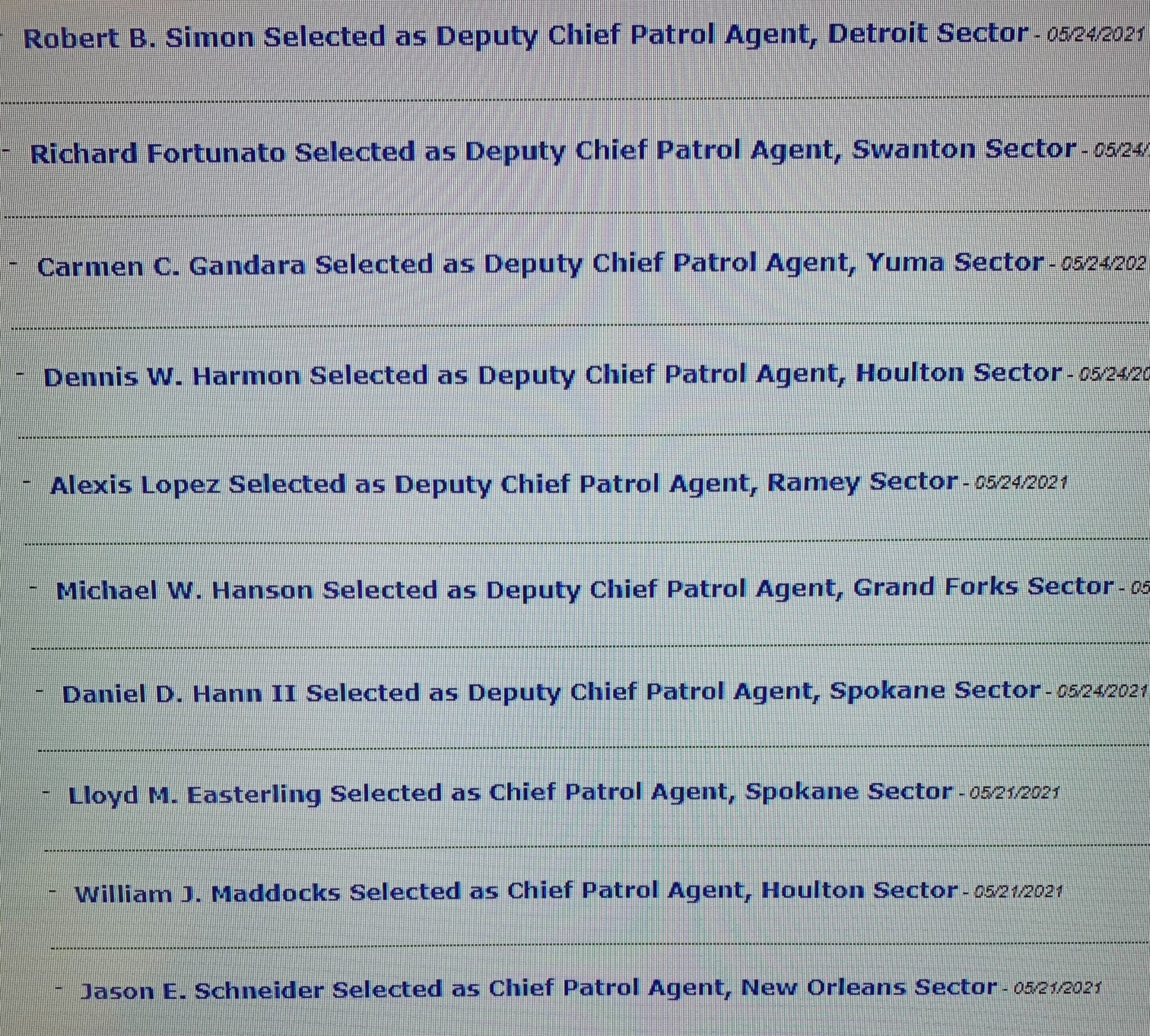

On May 21 and May 24, leadership promoted 10 regional officials, marking the first large group of promotions since Biden took office in January. A copy of the internal announcement provided to the Washington Examiner revealed that eight of the 10 are white, while the two others are Hispanic. Prior to this week, two other people had been promoted since January, one white man and a Hispanic man.

A senior CBP official leaked the list out of concern that the agency’s senior leadership wasn’t taking diversity seriously among management. The official had not applied for any of the positions and leaked the information in an attempt to sound the alarm.

“I’m getting texts from two different people,” the senior CBP official said, referring to when the announcement was made. “My white friends say, ‘This is bad. It looks like they’re all white.’ The Hispanic agents are like, ‘What the f***.'”

The promotion of one Hispanic man in Ramey, Puerto Rico, was likely to be “viewed as the least” noteworthy promotion nationwide because it is outside the continental United States. None of the chief positions went to Hispanic employees or women.

“I talked to a Hispanic coworker. He said how defeated, almost how accepting he is, ‘I knew what agency I joined,'” the same official added. “That’s what I lost some sleep over. I have some great coworkers who could be great leaders, and they just accept, ‘We’re not going to get the same opportunities.’”

Less than 20% of the Border Patrol’s field leadership nationwide is Hispanic, the CBP official said, citing internal statistics. CBP could not confirm or deny the claim. A recently retired senior agent admitted that the “field leadership does not represent the diversity of the workforce” and that the organization was “getting there at a snail’s pace.”

Brandon Judd, an agent who is also president of the National Border Patrol Council, said promoting employees based on skill is important, but that leadership has not acted on previously voiced diversity concerns. Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas spoke with agents in a town hall earlier this year, where he vowed to improve diversity in the agency.

While the union “does not and will not promote the hiring of people solely based upon skin color, rather we support hiring based upon talent and qualifications,” Judd added it is “hard for anyone to believe that in an organization that has more minorities than whites, hiring officials haven’t been able to find qualified and talented minorities. The law of averages clearly shows there is a problem.”

In a rare interview, Border Patrol national chief Rodney Scott spoke with the Washington Examiner to address the allegations and combat what he said was a “disgruntled” employee. Scott explained the promotional process from start to finish and gave reasons for why the recent promotions were overwhelmingly white employees.

“I’m the one that made the final selections, but building up to the recommendations is multi-layered. Many different people are involved to get different opinions and avoid any type of unconscious bias going forward,” said Scott. “We can always do better, but our promotions are not all white males.”

The 10 agents who were promoted in May have the highest government classification and pay, known as GS-15. Eight of the openings were for jobs on the U.S.-Canada border, one in New Orleans, and one in Puerto Rico. Human resources concluded 65 people who had applied for the 10 jobs were eligible for them. Of the 65, 45 were white agents, and fewer than half, 20, were Hispanic. No black, Asian, or other demographics applied. Of the 65, 62 were men, and three were women.

Scott said it made sense that more white than Hispanic employees sought jobs on the northern border based on what his team learned through recent discussions with employees: Hispanic agents are less likely to apply for promotions to places such as the Canadian border or coastal regions, where all of the recent promotions were for.

“We are also seeing a dynamic that may be unique to the Border Patrol. Most new hires and current agents are from the southwest border which are approximately 60 percent Hispanic. Many don’t want to leave home base and to move up in the agency you have to move around,” the agent wrote in a message. “I don’t know how many Hispanic agents are taking the supervisor test, really taking it seriously, and how many truly want to move away from home to move up in the Border Patrol. Many Hispanic agents are in the middle tier of Border Patrol field leadership and are content and happy where they are, because they are close to home.”

Scott said it is up to agents to “self-initiate” promotion applications, which is where the agency is running into issues.

Just 2,000 of the Border Patrol’s 20,000 agents are stationed along the Canadian border. The large majority of Hispanic employees are stationed on the southern border, which spans Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California.

“People get comfortable. They have families. And they have some hesitations to move, especially to places that are completely culturally different than where they’re currently at,” said Scott.

Beyond the comfort factor, Border Patrol found that because Hispanic agents did not want to leave the southern border, they could not complete transfers to the national office in Washington or gain experience in places such as Maine, North Dakota, or Miami. Without those experiences, they were ineligible for senior posts. Scott learned in discussions with agents in 2020 that while many Hispanic agents joined the Border Patrol after having grown up on the southern border, white and black agents often were from nonborder states. After the agents graduate from the academy, they are assigned to a random location. For black and white agents, it is often a big change that empowers them to seek out future moves because they have made it through the first one.

Employees who join the Border Patrol and are sent to a new geographical region are more likely to be willing to move elsewhere down the road.

“They’ve realized that there’s this whole other world, so they’ll be more willing [to relocate elsewhere] … because you ripped the Band-Aid off, went to the southern border, got exposed to a whole new culture, whereas [much of our Hispanic] personnel never left the border region where they grew up,” Scott said.

Scott hasn’t found a solution for the issue, but he said it was something that needed to be addressed. In the meantime, his office is focused on making the promotion process more transparent.

Agents seeking promotion are judged on their education and work experience. They must take a test that takes intelligence and technical knowledge into consideration. The test was first implemented in the 1990s and has been refined several times. It is currently being reviewed “to make sure it’s up to date,” Scott said. A list of the most qualified applicants is compiled then reviewed separately by three people. References are checked, and applicants may be required to submit a writing sample. A second panel of judges from the third-highest Border Patrol official’s office, law enforcement operations, will interview the candidates. Chief Manny Padilla, who is Hispanic, oversees that office and the hiring process after it has passed through human resources.

Scott’s right-hand man, Deputy Chief Raul Ortiz, is Hispanic, as is Padilla. The CBP official claimed Padilla, to the extent possible, is known for hiring white men in his office who are less qualified than their nonwhite peers. Scott denied it.

“Every allegation to a certain extent needs to be looked into. And I’m totally, totally open to trying to get better because anything that involves human beings can always get better,” said Scott. “You’re never going to get rid of some of this subjectivity, but at the end of the day, especially this level of leadership, promoting somebody for some type of bias as opposed to competency will destroy you as a leader. You can’t have people in these positions that aren’t fully competent.”

The anonymous CBP official said that agents who are frustrated with a perceived lack of opportunity fear filing an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission complaint because “their career is over” if they go that route.

“First off, that’s not true about the EEO process,” Scott said. “You should use it, but there’s no reason you can’t just talk to your supervisor and or ask for a meeting with the selection officials either.”

Over the past year, Scott and Ortiz rolled out a career development plan that explains how agents at any level can be eligible for a promotion. At this point, it is more of a guide that would not apply to agents who are “grandfathered in” to previous standards. All promotions are published internally, and the thought process behind them is explained for agents to understand.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“We’re making sure that we give our workforce the best leaders we possibly can to be effective, moving forward, and that we are transparent about it,” said Scott. “My bottom line for the American public and the front-line agents, we have to provide them highly competent leadership. There’s just too much at risk. We can’t get into a just check the box quota thing. We have a diverse leadership team, and they are highly, highly capable, and they earned it. It wasn’t given to them.”

The CBP official said Scott does not have a “racist bone in his body,” but he is “not surrounded by people” who share his vision for diversity.

Correction: A previous version of this story referred to the deputy chief promotion in Puerto Rico as a woman and was updated to reflect the individual promoted was a Hispanic man.