Defense ministers from NATO’s 30 member states are meeting at the alliance’s headquarters in Brussels.

Led by the capable Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg, the alliance is trying to evolve. Recognizing China’s preeminent threat to the democratic international order that NATO stands for, the alliance is paying more attention to Beijing (albeit to the chagrin of France, which worries about losing Chinese trade).

The alliance is also focused on better deterring the threat posed by Russia. President Vladimir Putin last week ordered the closing of NATO’s office in Moscow. In turn, Stoltenberg warned that “the relationship between NATO and Russia is now at a low point. It has not been more difficult since the end of the Cold War.” Stoltenberg has announced a new innovation fund worth at least $1.1 billion USD (a NATO spokesperson did not respond to my question as to whether any member states had made specific pledges to the fund). NATO also seeks a greater forward presence in and around the Black Sea.

These are positive, if overdue, actions. The problem is that they represent metaphorical clothes, not meat, on the bones of NATO’s credibility.

The main problem is a familiar one — money. For all the fine rhetoric about how NATO represents shared resolve in a common cause, the alliance remains divided between the givers and the takers.

Okay, it’s a little more nuanced than that. France, for example, will barely scrape by the 2021 NATO minimum defense spending target of 2% of GDP. President Emmanuel Macron also wants to remove sanctions imposed on Russia following its seizure of Crimea from Ukraine. At the same time, however, France will boost defense spending next year. France is also willing to deploy its forces on some of the most sensitive NATO operations. And, it must be said: Macron has a somewhat legitimate gripe over the Biden administration’s handling of the AUKUS submarine accord (although Biden could repair things and thereby counter China).

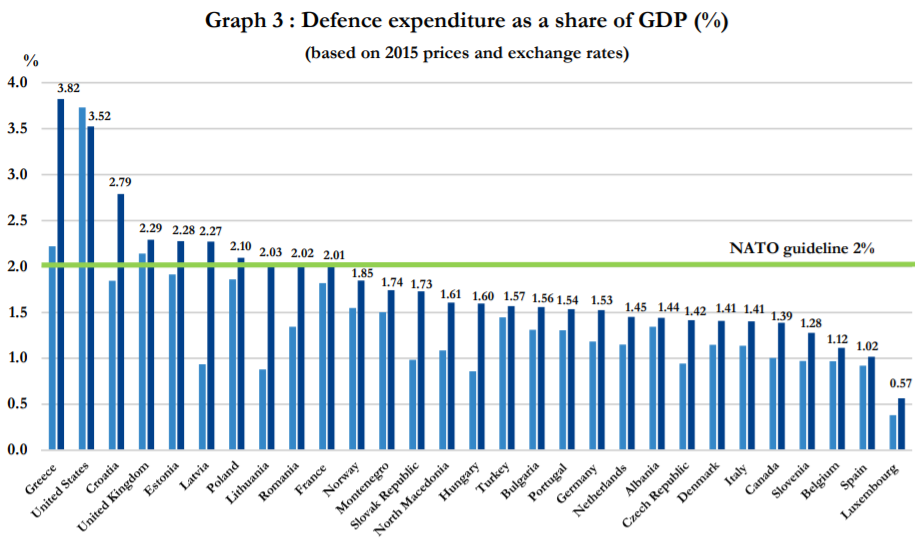

Still, NATO’s latest figures show that only Britain, Croatia, Estonia, France, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, and the United States are expected to meet the 2% target this year. As illustrated by the NATO graph below, many of the other 21 member states continue to fall well short of the target.

This is simply unacceptable. Indeed, seven years after a NATO summit in which all members agreed to move expediently toward the 2% target, these figures undermine NATO’s very credibility. They also explain why Russia has been able to exploit gaps in the alliance’s armor.

Leading the deficient defense pack is Germany. There is no better proof of outgoing Chancellor Angela Merkel’s ludicrously undeserved reputation as a defender of the international order. In 2021, Germany will spend just 1.53% of its GDP on defense. Belgium, which hosts NATO’s headquarters, is projected to spend just 1.12% of GDP on defense. Moreover, these rich nations are two of only five member states expected to fail to meet the alliance’s target of spending at least 20% of their defense budgets on equipment.

There’s a defining irony here. Germany’s former defense minister and Belgium’s former prime minister (who once laughed in former President Donald Trump’s face as he legitimately called for increased European defense spending) are now the two presidents of the European Union. This record speaks to the disdain with which too many European powers regard collective security. They prefer freeloading and strategic appeasement.

If and until that changes, the U.S. should determine how to consolidate allies such as Britain, the Baltics, Greece, and Poland, which face the greatest threat from Russia and are thus willing to share burdens in our common defense. One idea: Relocate some U.S. military forces from Germany to Poland.