DETROIT — Fourteen inspection lanes are all that stand between 6,200 tractor-trailer trucks moving goods from Canada into the United States at the northern border’s busiest crossing point. If just one inspection lane at Detroit’s Ambassador Bridge closes, it can cost the private sector millions of dollars for every hour it’s shut down.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers stationed at the port enforce 500 trade laws and regulations on behalf of 49 agencies. And they must do so quickly and carefully because the country’s economic welfare and national security are at stake.

“We know that what we do here is critical to the economy of the United States. So much freight comes through the corridor from upstream in Ontario and up in Quebec, down through the ports that are in southeast Michigan. So much of that comes through that if we don’t do our due diligence and be as efficient as we possibly can be … then we’re having an economical ripple downstream,” said Jeffrey Watkins, port watch commander.

CBP recently agreed to give the Washington Examiner an exclusive tour of the 46-acre port to see firsthand how drug smuggling is caught by federal law enforcement officers, and other things they manage to find.

Looking for a needle in the haystack

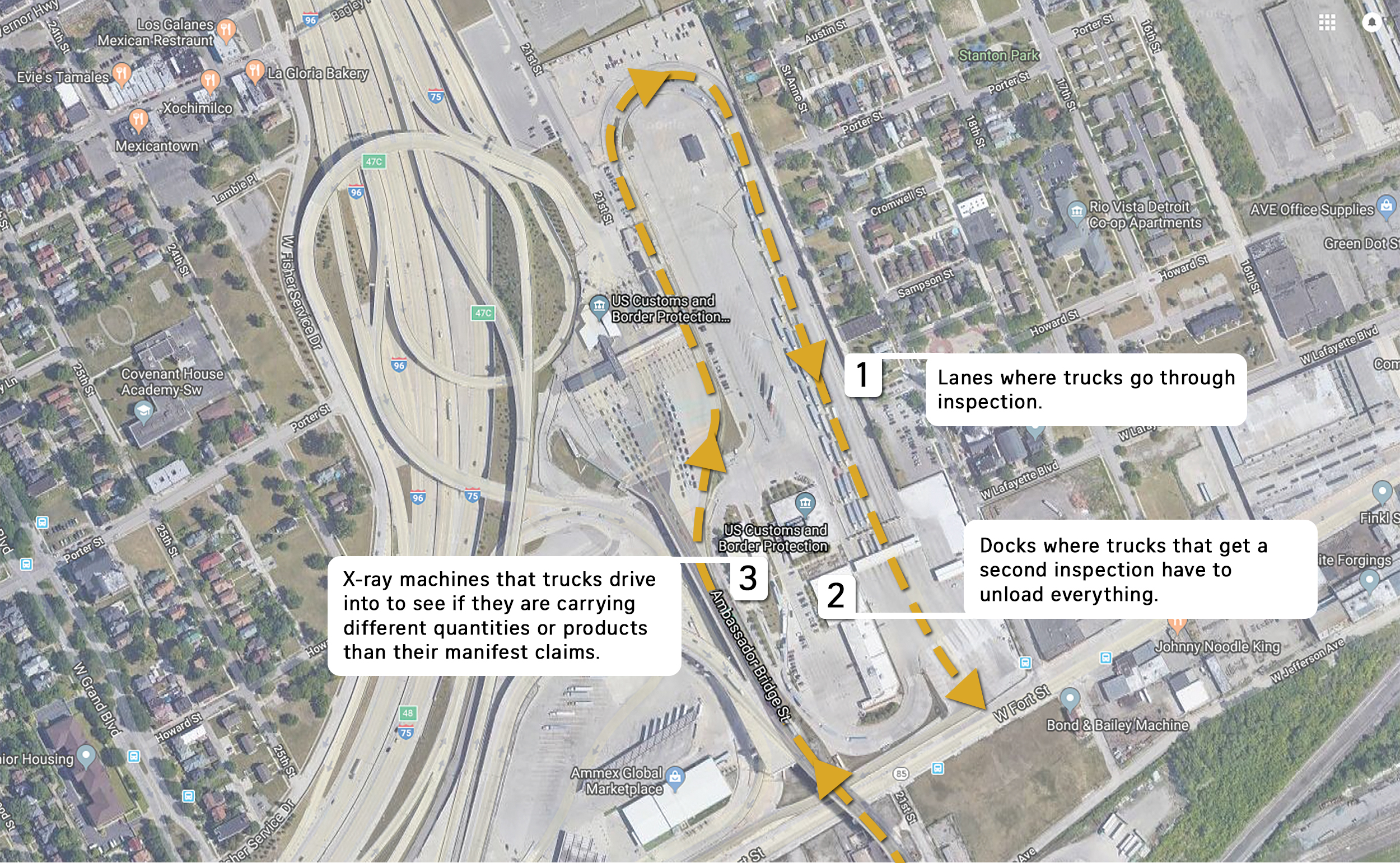

Tractor-trailers crossing the Detroit River into the U.S. will take a right lane exit off the bridge and make a 180-degree turn on the off-ramp where — depending on which lane they need to be in for processing — they can pick one of 14 lanes..

At any time on any given day, that quarter-of-a-mile-long road is crammed full of trucks, sometimes stacked up back onto the bridge. The trucks go as far as the eye can see. Each truck grunts as they inch their way forward, then squeal when drivers hit their brakes. It happens again and again.

“The reason why this is the busiest,” said Kris Grogan, spokesman for CBP’s Detroit Field Office. “It’s very simple. It’s the auto industry.”

The Detroit field office, which encompasses land borders, international airports, ferry service, train tunnels, and small vessels, processed $139 billion of imports in fiscal 2017 and handles $381 million daily.

Most of the trucks lined up in the queue waiting for their initial inspection are bringing legitimate goods into the U.S. Some are bad actors, yet others don’t even know they’re hauling contraband, such as guns, narcotics and people.

The majority of drivers caught hauling unlawful or regulated items in the trailer are not arrested.

“Even if it’s contraband, nine out of 10 times … the driver is just picking up a load. He doesn’t know what’s on that load. It’s been sealed and everything. A lot of times we’ll find that seizure, you know, it’s narcotics. We’ll release them and then release the truck and the driver,” Grogan said.

Modern smugglers

CBP officers at the port are not your average law enforcement agents, and they’re certainly not toll booth operators. They’ve graduated from a rigorous 18-week program in Glynco, Ga., then completed a 34-week training course at Ambassador Bridge. By the time they’re cut loose, they know exactly what to expect and can spot unusual paperwork or activity within seconds.

September marks the last month of fiscal 2018, and as of halfway through the month, Detroit was leading the nation for having seized the most illegal guns.

Detroit’s smuggling business is more established than other cities’, both officials said.

“People don’t realize Detroit is where smuggling began — prohibition,” Grogan said. “Those families and stuff that were running booze back in the prohibition days, they’re still in business. They’ve just changed their commodities for the time.”

With homeland security on the line, nothing is too small to send the truck for a secondary inspection. Every tractor-trailer that arrives at the port is screened by radiation plates to ensure a bomb is not being transported. But beyond that, it’s up to the officers to consider every other threat that could be on board.

Watkins does not have the manpower to open anywhere near the 6,200 trucks coming through his port on a daily basis. He relies on “force multipliers” — a term echoed throughout the Department of Homeland Security that refers to a multi-level approach — to catch non-compliant trucks.

Try, try again

If an officer determines something is fishy about the driver, the cargo, or the truck, it will be sent to one of more than a dozen loading docks to have its trailer looked through or it will be directed to a two-story garage to be X-rayed. The driver will exit the vehicle for his or her safety while the truck is scanned by the machine. The process is typically used to ensure drivers are transporting the quantity and type of items they claim to be.

If sent for an enforcement inspection, the officer is most likely concerned about potential contraband onboard or may be trying to ensure that a company that has previously violated the law before is complying now.

Inside the main CBP building are loading docks for trucks that need a physical inspection. It’s late Friday afternoon and the slowest time of the week for the 24/7 operation so only one truck is at the dock.

Its back door has been opened and all of its unloaded cargo is stacked on pallets and sitting a few feet inside the room. The officials note on a normal weekday, every dock is filled with trucks being unloaded, inspected, and loaded back up — except for the ones found carrying contraband. Any illegal or unapproved regulated cargo found on board will be escorted to one of several secure rooms in another part of this port building.

The broker or shipper hire stevedores to remain on site at the port in case trucks are sent around for a physical inspection. CBP will either instruct these professional truck loaders to remove everything from the tractor-trailer for officers to look over or a CBP officer may be able to walk into the truck and examine its freight without having to further delay the driver.

Speed is money for these shippers, and the “great, great majority” of trucks that are sent for a second inspection are cleared to leave and not in violation of any laws.

But for those in narcotics, firearms or other illegal items are found, CBP will notify U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Homeland Security Investigations arm, as well as the local United States Attorney to see if the two want to investigate and prosecute the trafficker, respectively. CBP acts as the street cop while HSI serves as the detective.

“We are effective at catching the small-time auto thief and we are effective at catching those auto rings that are shipping vehicles across water to other parts of the world. We do know that what we do here has an impact on terrorist organizations because what we stop here has a ripple effect on their financial capability to put their operations in motion,” Watkins said.

The agency will also look into whether the contraband was intended for Detroit, a different U.S. city, or for Central America, then pass that information onto Department of Homeland Security partners.

Years ago, truck drivers would present a paper manifest, or document stating what was on board, at international ports. Now, that process is entirely electronic. The driver, broker or shipper must submit an electronic list of items on board at least one hour before his or her arrival to Ambassador Bridge. It gives CBP the chance to look at who is coming and an opportunity to decide ahead of time who needs to get a more thorough look following the first inspection.

If no flags are raised, a truck can be in and out of that checkpoint booth in a matter of minutes. The process flows especially quickly for trucks enrolled in CBP’s pre-clearance program.

Free and Secure Trade for Commercial Vehicles, known as FAST, provides expedited screening for low-risk shipments hauled by drivers who have passed background checks. The entire supply chain — from manufacturer to driver to importer — must be certified through the Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism program. The program is similar to airplane passengers who are members of the Transportation Security Administration’s Global Entry.

NFL’s interest

One particular private entity has a greater interest than most when it comes to trucks’ cargo: The National Football League. Its main mission is to educate CBP officers on imposter merchandise, and the NFL sends its own import specialists to ports around the country to explain what a genuine watermark looks like and other ways to identity authentic gear so that they know when they are looking at fake jerseys.

ICE seized $20 million — or 260,000 counterfeit Super Bowl-related items — ahead of the 2017 game in Houston. Those goods would have been sold on the black market and cost the NFL millions of dollars in revenue.

In all of last year, CBP seized $1.2 billion of items that violated intellectual property rights laws.

But for every move and victory on CBP’s part, bad actors are watching and taking note.

“When we change our methodology and we have success, they change their methodology ‘cause they’re professionals. They’re professional smugglers. They’ve been at it for years or for centuries,” Watkins said. “It’s no different than the cartels on the southern border.”

In a recent outbound operation in which truckers leaving the U.S. for Canada were stopped for surprise inspections, CBP found out some had passed on word about the sting to other drivers.

“By the time we jump up there, truckers are telling other truckers all the way down to the Ohio line that we’re doing this. Everyone’s watching what we’re doing,” Watkins said.

$2.4 trillion in imports

Once trucks pass through the checkpoint, the enforcement operation has ended, but the compliance portion of CBP’s duties are beginning and the shipper or broker will have 15 days to validate the manifest and pay the government duties, tariffs and other fees.

Last year, CBP inspected 33.2 million vehicles and 28.5 million cargo containers coming into the U.S. for a total of nearly $2.4 trillion in imports. The agency raked in more than $40 billion in duties, taxes, and other fees, making it the second-highest revenue creator in the federal government after the Internal Revenue Service.

At the 4,000-mile-long continental northern border, approximately 400,000 people and $1.6 billion in goods crossed daily.

“One of our threats really is the unknown. What could happen?” Grogan asked.

“This year alone, we’re already at 89 different countries of individuals that we’ve arrested people from. That’s unprecedented from anywhere else in the country,” he added. “So it’s the unknown: what is trying to come in?”