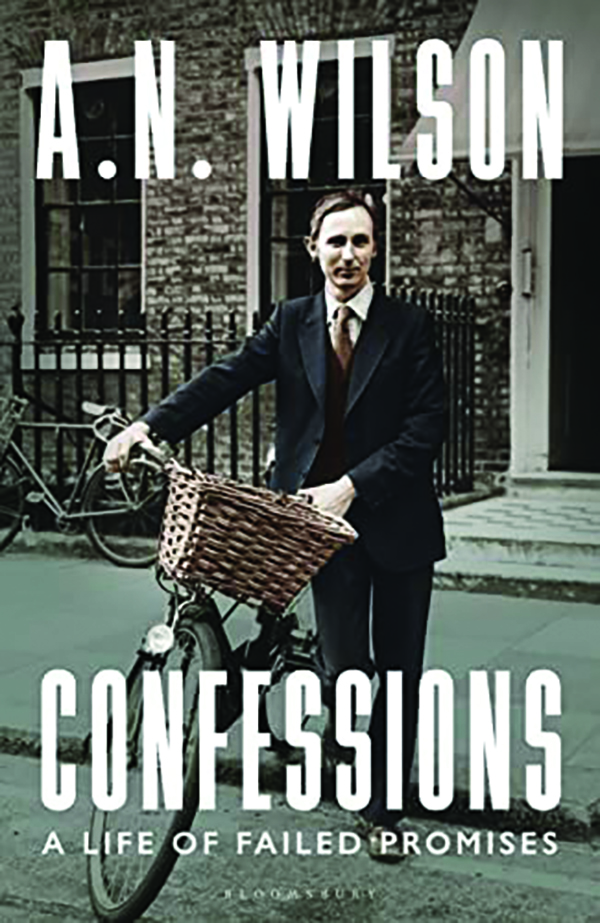

“I have never suffered from ‘writer’s block,’” A.N. Wilson announces at the beginning of his memoir, Confessions: A Life of Failed Promises, but he adds quickly that despite writing so much — “fifty books published, and probably millions of words in newspapers” — his concern has always been “to match the words to the truth of experience.” His life has been “the intolerable struggle / With words and meanings,” to quote T.S. Eliot in “East Cocker,” which Wilson does.

He is, he wants to say without quite saying it, a prolific and talented writer — not great, mind you (“I am not worthy to lick the books of either Jane Austen or Tolstoy”), but not minor either: “I suppose that whatever I might have achieved as a writer would have been on the large canvas, and not the small piece of ivory.”

And it is remarkable how much good writing Wilson has published in his lifetime. The Victorians is a vivid and nuanced history. His novel Wise Virgin is a minor masterpiece.

But it’s an awkward start to a memoir, especially one called Confessions, that is, by turns, entertaining and dry (pages upon pages of who said what at lunch), touching and self-serving, full of good sense (such as when he lambasts “trendy vicars” who made bank in the 1960s marketing their unbelief) and hyperbole (marriage is “utterly destructive to the human soul”).

There is some contrition, too, of course. He feels bad for cheating on his wife, who was an academic and 10 years his senior. His father was a master potter whose art meant so much to him, and Wilson regrets not traveling with him to Korea. He admits to being stubborn and selfish, to being in love with love (like Augustine), but he’s careful to provide details that get him partially off the hook. So be it. We already have one Augustine. We don’t need another.

The book can be broken into two sections: “My Parents” and “Famous People I Knew.” The events of his life to his late 30s (the book ends with the publication of his Leo Tolstoy biography in 1988) are recounted more or less sequentially, though one memory evokes another, and Wilson jumps around in an interesting way.

His parents, Norman and Jean, did not get along. His father was an atheist, vain and boisterous. His mother was a devoted churchgoer and vindictive. She had an “unrivalled capacity to extract unhappiness from any situation,” Wilson writes.

This isn’t to say that Wilson had an unhappy childhood. Despite their flaws, his parents were as good to him as they could be, and he spent most of his time away at school, which, after an abusive headmaster was removed, was largely a pleasant experience, with a handful of devoted teachers and pleasant classmates.

It was in rugby that he first experienced the thrill of journalism. He was the editor of the school newspaper, and ahead of Queen Elizabeth’s visit to the school to open new gates to mark its 400th anniversary, the young Wilson wrote an editorial arguing that she should open all public schools to all children, regardless of parents’ ability to pay. This was picked up by the Daily Express, and Wilson became the “Public School Red” who had insulted the Queen. He was “aglow.”

The article was a piece of “cheap journalism,” he writes, which he had learned from reading “half-truths in emotional journalese” in the News of the World. If he hadn’t experienced “the excitement” of that kind of writing, “I should probably have been a better person,” but he is clearly still proud of the splash he made.

Oxford would follow, and then several unsatisfying years of marriage and teaching. He became good friends with his tutor, Christopher Tolkien, who managed to get Wilson appointed as his replacement when he decided to leave Oxford for France. The appointment didn’t last, but just as it became clear that his time at Oxford was coming to an end, he received a phone call from the Spectator offering him the post of literary editor.

In London, Wilson worked, met with friends, and worked some more. He was known for his three-piece suits, not escapades with actresses, drugs, and debauchery (though he did his fair share of drinking). So instead of scandal, what we have in this section of the memoir is a string of lunches and conversations with royalty and mildly famous individuals. There is the queen of Denmark, Martin Amis, various mid-level English and French aristocrats, the Tolkiens, the queen mother (a fan of his Life of John Milton, by the way), L.S. Lowry, Rowan Williams, John Betjeman, Harold Wilson, Malcolm and Kitty Muggeridge, and many others.

“Pride is an insufferable quality,” Wilson writes, but vanity is “endearing.” He says this about his father, but there is a fair bit of vanity in Confessions, too, which, if not endearing, isn’t so transparent as to be off-putting. It helps that Wilson knows how to tell a good story, and so even plays for vanity are frequently salvaged by character details that bring a scene to life.

Wilson is at his best, however, when he writes about minor figures, like his memories of walking to school with “Blakie,” a woman who helped in the Wilson house, who loved him, he felt, “with complete lack of reserve.” Or, there is his memory of spending a few weeks every summer studying French with one Madame de Liencourt, who organized tennis or sailing lessons during the day and gave French lessons in the evening around the dinner table.

He has a soft spot for people who have been “overtaken by the heartless movement of history …whose spiritual home is the last ditch,” perhaps because he, too, feels that he has been overtaken by history. In some ways, the book is about these people: His father, Blakie, one Sgt. Major Bates, wearing “gleaming black boots and dazzling Blanco-ed spats” and drilling boys in outdated weaponry while they sing Rolling Stones songs.

Wilson captures a world that is smaller than today but also full of possibilities too soon passed. This may not be a confession, but it is a lament, and rightly so.

Micah Mattix is a professor of English at Regent University.