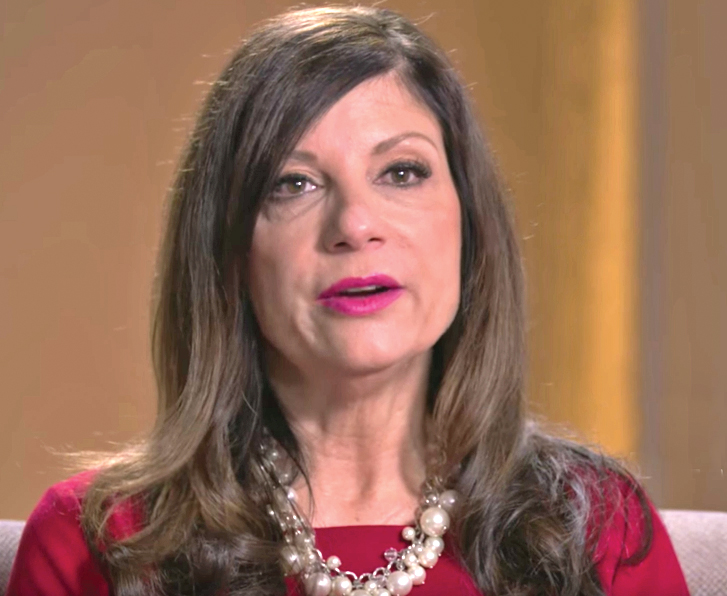

For decades, Leslie Millwee has been haunted by a series of traumatic memories. As she alleges, on three occasions between March and August 1980, when she was just 20, the governor of her state sexually assaulted her at work. The three attacks, spaced roughly two months apart, were all similar. On his visits to the small town where she held a job as a newscaster, the governor, whom she had previously interviewed at various local events, would head over to her TV station. He would then dash into the small room where she edited her stories. Standing behind her, he would grab her breasts. The first attack, Millwee says, lasted two or three minutes. The next two both lasted five to seven minutes and ended with him ejaculating. A couple of years ago Millwee, who now works in community relations for a hospice in Palm Springs, Calif., finally summoned up the courage to go public with her story. These days she often tweets about these painful incidents. Surprisingly, even in the era of the #MeToo movement, which marked its first anniversary a few weeks ago, the mainstream media continue to ignore her.

The reason for this radio silence may well have something to do with the identity of the powerful man Millwee claims victimized her. A dozen years after the alleged assaults, that governor was elected president of the United States. His name is Bill Clinton. “There seems to be a double standard that protects prominent liberals,” says Millwee. “All of America listened carefully to the Senate testimony of Christine Blasey Ford, who claims that she was violated by a conservative over 30 years ago. But few people seem interested in what I have to say. And in contrast to Brett Kavanaugh’s accusers, I can give a specific time and place for the assaults and supply lots of corroborating evidence.” Clinton has never responded to Millwee’s accusations.

In the 20 years since the House of Representatives voted to impeach Clinton, a dominant narrative about his sexual misconduct has been sustained—that it was all much ado about little. This view is rarely challenged, even though it’s essentially the one authored by Clinton himself. In his autobiography My Life (2004), Clinton admitted to two consensual affairs—with Gennifer Flowers, who, like Millwee, worked as a TV journalist in Arkansas, before becoming a cabaret singer, and with Monica Lewinsky, whom he met during her stint as a White House intern. Clinton also acknowledged lying under oath about what he called his “immoral” and “foolish” behavior with Lewinsky—the infraction that led to his impeachment and eventually resulted in the suspension of his law license for five years.

As Hillary Clinton began to pursue her own presidential ambitions, most Americans assumed that the sum total of her husband’s sins amounted to little more than that. Perhaps Clinton was an inveterate womanizer whose fessing up to just two adulterous relationships constituted a whitewash—so went the common refrain—but if his wife was at peace with his sexual past, the details were nobody else’s business. This governing assumption took a hit last fall after Ronan Farrow published his New Yorker piece exposing numerous allegations of sexual harassment against Harvey Weinstein. Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, the New York Democrat, said she now believed President Clinton should have resigned in 1998. And a few influential journalists—including New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg—argued that the rape allegation of Juanita Broaddrick deserved a second look.

In early 1999, just a couple of weeks after Clinton’s acquittal by the Senate, in an extended interview with NBC’s Dateline, Broaddrick, the former owner of an Arkansas nursing home, gave a harrowing account of an assault in a hotel room in 1978. “I met Clinton at 8:30 in the morning for a business meeting,” Broaddrick recently told me. “He attacked me within five minutes of entering my room.” Other than having his lawyer issue a brief denial of the allegation back in 1998, Clinton has said nothing about Broaddrick, who, like Millwee, does not get a mention in his memoir.

By June 2018, when Clinton, along with his coauthor James Patterson, the mega-bestselling novelist, toured the country to promote their thriller The President Is Missing, the status quo ante reigned supreme once again. In book-tour interviews by the national media, Clinton received mostly softball questions. The one exception was when Craig Melvin of the Today show asked Clinton if he owed Lewinsky a personal apology. After responding that this was not necessary since he had already issued a public apology, the former president played the victim: “And nobody believes that I got out of that for free. I left the White House $16 million in debt. . . . This was litigated 20 years ago.” While Clinton was widely rebuked for his tone deafness, just about everyone agreed that the Lewinsky scandal had indeed been discussed ad nauseam and that it was time to move on.

But the credible assault allegations raised by both Millwee and Broaddrick suggest that the former president’s affair with a 22-year-old intern, which Lewinsky recently termed “a gross abuse of power,” may well be just one link in a long chain of predatory behavior that dates back to the late 1960s. In fact, the complete list of Clinton accusers alleging sexual assault or harassment is far longer than many realize. It includes not only Kathleen Willey, a former White House volunteer, and Paula Jones, a former Arkansas state employee, who both aired complaints that circulated widely during his presidency, but also at least a half dozen other women who received just a brief flurry of media attention in the 1990s: Eileen Wellstone, who claimed that Clinton tried to rape her at Oxford in 1969; an unidentified Arkansas lawyer who told a Clinton biographer that he tried to force himself on her in 1977; Carolyn Moffet, an Arkansas legal secretary who reported that Clinton demanded oral sex in 1979; Elizabeth Ward Gracen, who told friends that Clinton tried to rape her shortly after she was crowned Miss America in 1982; Sandra Allen James, a political fundraiser who stated that Clinton put his hand up her dress in 1991; and Cristy Zercher, a flight attendant who charged that Clinton fondled her breasts during the 1992 campaign.

In the #MeToo era, the mainstream press would not hesitate to do a deep dive into the sexual history of any other internationally known former head of state facing such a string of disturbing allegations. Remarkably, the two lines of defense that team Clinton trotted out during his presidency still seem to protect him from such scrutiny. One was the farfetched contention that all his accusers belonged to a “vast right-wing conspiracy.” This was the expression that Hillary Clinton whipped out in the infamous Today interview in January 1998 in which she denied the initial reports of her husband’s affair with Lewinsky. When asked last week by CNN about how the assault allegations against her husband compare to those against President Trump, the former first lady reverted to the same talking point: “There’s a very significant difference, and that is the intense, long-lasting, partisan investigation that was conducted in the ’90s.” She also rejected the idea that her husband’s affair with Lewinsky was an abuse of power, telling a CBS interviewer that Lewinsky “was an adult.”

The other line of defense was the Clinton camp’s misogynistic slime machine, which most Americans forgot about years ago (or are simply too young to have witnessed or remembered). This widespread amnesia was on full display a few weeks ago at the Atlantic Festival when Lindsey Graham, in response to a question about whether President Trump had made disrespectful comments about Christine Blasey Ford, repeated the notorious line that Clinton aide James Carville had used to discredit Paula Jones: “This is what you get when you go through a trailer park with a $100 bill.” The crowd gasped, assuming that the Republican senator from South Carolina was casting aspersions on the character of Ford rather than attacking Democratic hypocrisy when it comes to women making accusations of sexual assault.

Carville’s comment about Jones was not a throwaway line but part of a carefully orchestrated strategy that dates back to the early days of the 1992 campaign. That’s when the candidate asked aide Betsey Wright to head up a quick-response team designed to fend off what Wright called “bimbo eruptions.” Wright, in turn, funneled over $100,000 to a San Francisco private detective, Jack Palladino, to dig up dirt on Gennifer Flowers and the roughly two dozen other women whom she determined might talk to the press about sexual encounters of one sort or another with Clinton. Dubbed “the bimbo buster” or “the president’s dick” by Clinton aides, Palladino would use the threat of character assassination to intimidate the women into signing affidavits denying any sexual involvement with the candidate. He would also try to induce news outlets to spike potentially damaging stories before publication. As Ronan Farrow noted last fall in the New Yorker, Palladino is the fixer Harvey Weinstein hired two decades later to compile hefty dossiers on accusers such as actress Rose McGowan, though in his Pulitzer Prize-winning stories, Farrow never got around to mentioning Palladino’s prior (and highly effective) work for Clinton.

To understand how Bill Clinton has surmounted allegations of sexual assault serious enough to have doomed many a powerful man, we have to go back to the early days of his career in Arkansas. Clinton’s rampant infidelity was already an open secret in both political and media circles in the state by the time he was first elected governor in 1978. In 1980, when Millwee began working at the TV station in Fort Smith, she was well aware of his history. “Everyone in the newsroom knew about his affair with a TV reporter in Little Rock, though we didn’t know Gennifer Flowers by name. When he started becoming excessively flirtatious with me on his various trips to the station before the assaults, my colleagues started joking that he was now looking for another lover in Fort Smith,” she says. “But all this talk made me very uncomfortable, as I wasn’t at all interested in that.”

Dolly Kyle, an Arkansas lawyer who met Clinton while they were both in high school, testified under penalty of perjury in the Paula Jones case that she had engaged in an on-again, off-again consensual affair with Clinton for nearly 20 years beginning in the early 1970s. “During an overnight tryst in May of 1987 at an airport hotel in Dallas, Clinton confided in me that he was a sex addict,” says Kyle. “He claimed that women threw themselves at him, and he didn’t know how to control himself. He admitted that by then he had already had at least a few hundred sex partners since his marriage.” About a month after this discussion with Kyle, Clinton made the surprising announcement that he would not run for president the following year. This was not long after Democratic senator Gary Hart’s once-promising presidential campaign suddenly collapsed amid news reports of adulterous behavior, and the Clinton camp was concerned that their candidate could well meet the same fate.

Though Clinton’s relentless pursuit of extramarital sex continued more or less unabated, it did not cause any political problems for a few more years. The first sign of trouble came in October 1990 when Larry Nichols, a disgruntled former state employee, filed a $3 million lawsuit against Clinton, claiming the governor had misused state funds to carry on affairs with Gennifer Flowers and four other women. In a New York Times Magazine article in early 1997, journalist Philip Weiss would call Nichols’s lawsuit “the declaration of war by those I’ve come to think of as Clinton crazies.” But while Nichols and other Clinton enemies would latch on to a slew of conspiracy theories over the years—including wild charges of drug-smuggling and gun-running—there was nothing glaringly delusional about these particular sexual allegations.

The Clintons are correct in maintaining that political opponents repeatedly tried to use sex scandals to their advantage; that’s what political opponents do. However, it does not follow that all the stories of sexual liaisons were manufactured out of whole cloth. As one biographer noted, “There were simply too many women and too many stories to be a matter of a temporary lapse or of smears by opponents.” Clinton soon got all five women to sign affidavits denying Nichols’s allegations, but those documents were hardly proof of anything. In fact, a taped phone conversation from 1991 reveals that Clinton urged Flowers to lie, telling her, “Hang tough . . . all you got to do is to deny it.” In early 1992, Flowers flipped, claiming in a story she sold to a tabloid that she had had a 12-year affair with Clinton. Right before the New Hampshire primary, Clinton was forced to do damage control. In a widely watched 60 Minutes interview after the Super Bowl, with Hillary sitting by his side, he admitted that he had “caused pain in my marriage.” This vague confession of limited adulterous behavior managed to quell the furor and clear his path to the White House.

In late December 1993, Clinton’s reckless sexual past came back to haunt him once again when both the Los Angeles Times and the American Spectator reported that as governor, he had asked Arkansas state troopers to procure women for him. Entitled “His Cheatin’ Heart,” the Spectator story set out to discover something about the roughly two dozen “bimbos” whom the Clinton campaign feared might “erupt” before the 1992 election. Except for Gennifer Flowers, author David Brock did not identify any of the women by name. Based on 30 hours of interviews with four state troopers, Brock wrote of a governor who, in addition to asking his staff to set up assignations with strangers, was juggling a half-dozen steady girlfriends.

Team Clinton, which would eventually come to include Brock after his political conversion memoir Blinded by the Right (2002), never pushed back against specific allegations. Instead, they spoke of right-wing smears. As the former president argued in 2004, Brock’s article could be traced back to “extraordinary efforts made to discredit me by wealthy right-wingers with ties to Newt Gingrich and some adversaries of mine in Arkansas.” Some of the salacious details may well have been embellishments. However, the overall portrait of Clinton’s predation is consistent with what numerous other people have reported—consensual partners like Flowers, Kyle, and Lewinsky, as well as the various women alleging assault.

The Spectator story included a brief allusion to a woman named Paula whom Clinton had asked the troopers to set him up with soon after he spotted her at Little Rock’s Excelsior Hotel in May 1991. Three years later, that woman, Paula Jones, filed a sexual harassment suit against the president for the crude proposition that she alleges happened inside that hotel room. Jones’s lawsuit dragged on until November 1998, when Clinton agreed to pay her $850,000, though he never acknowledged any wrongdoing. Along the way, as Jones filed appeal after appeal, news of the Lewinsky affair made it onto the radar screen of Ken Starr, the independent counsel initially charged with investigating the Whitewater scandal, a failed Arkansas real-estate investment implicating the Clintons. And Starr, in turn, recommended impeachment for perjury and obstruction of justice, stemming from Clinton’s attempt to cover up the Lewinsky affair in his Jones case testimony. To pay her legal costs, Jones relied on financial support from conservative groups such as the Rutherford Institute, but, again, that does not impeach her testimony in the “he said/she said” debate she waged with the president, as the Clinton camp repeatedly insisted.

The Clintons are also correct to point out that his sex scandals were litigated in the late 1990s when, after careful consideration, the vast majority of Americans sided with their president—at least on the narrower issue of whether he should be removed from office for lying about them. But that’s actually a compelling reason to revisit them in the #MeToo era.

Twenty-five years ago, journalists were still searching for the proper conceptual lens through which to examine the sexual behavior of presidents. As the Los Angeles Times noted in its 1993 article on “Troopergate,” “Allegations about the personal lives of Presidents are not new. While President, Thomas Jefferson was publicly accused by a disgruntled former supporter of having an intimate relationship with one of his slaves. . . . For most of this century, propriety generally required that such matters be discussed only after the individual leaders were no longer alive.” Until very recently, presidents were often idealized, and allusions to the extramarital affairs of any president—particularly widely revered ones like Jefferson and John F. Kennedy—still made most Americans uncomfortable. That’s why nearly all presidential scholars failed to pursue the historical evidence pointing to Jefferson’s long-term sexual relationship with his slave Sally Hemings. And given that sexual harassment was, in the 1990s, just beginning to be acknowledged as a social ill, the possibility that any head of state—past or present—might have been guilty of it still seemed somewhat fantastical to many.

Over the past couple of decades, a consensus has emerged that during the Clinton administration the mainstream media went too far in the other direction, throwing propriety to the wind. As Marvin Kalb, the founding director of Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on the Media, Politics and Public Policy, put it in One Scandalous Story (2001), “When the story broke on January 21, 1998, that President Clinton had had an affair with . . . Lewinsky, the press plunged into the scandal, disclosing every tasteless detail. Its self-justifying explanation was that it had no choice.” The press certainly deserves criticism for its obsessive focus on the most titillating aspects of the Lewinsky scandal. However, it’s important to locate the lust responsible for the media frenzy primarily within the former president himself—and not project it entirely onto journalists, as the Clintonistas were wont to do. In The War Room (1993), a documentary about Clinton’s first presidential run, deputy campaign director George Stephanopoulos, now the chief anchor of ABC News, urges a radio talk show host not to cover some new sexual allegations about Clinton, barking into his phone, “People will think you’re scum.”

While the #MeToo movement has detractors who worry about its excesses, it’s hard to find any American who denies its important lesson that throughout history, a small but significant percentage of men in high places—of all races, faiths, and political persuasions—have had little compunction about forcing themselves upon women and then lying about this criminal behavior.

It’s time to listen carefully to what Leslie Millwee and all of Clinton’s other accusers have to say. With Bill and Hillary Clinton now embarking on an extended tour of North America—live events begin in Las Vegas next month and end in Los Angeles next May—the time is ripe for a deliberate and dignified national conversation about whether our 42nd president is actually a sexual predator who has long been hiding in plain sight.