The Associated Press announced on Wednesday afternoon that Democrat Andy Kim had squeaked out a victory against incumbent Republican Tom MacArthur in New Jersey’s 3rd District. It was a symbolic result in the narrow view of recent history: Democrats tried to make the 2018 elections about preserving core parts of Obamacare, and MacArthur led negotiations (from House Republicans’ moderate flank) to create a salable bill to repeal the law.

But his loss was indicative of the country’s longer-term lurch toward tribalism. The Garden State now has just one Republican in its congressional delegation—the lowest representation for the GOP there in more than a century.

New Jersey is, by meaningful statistical measures, a modern “blue state.” Throughout the 20th century, it bounced between electing members of both major parties governor, including moderate Republicans Tom Kean and Christine Todd Whitman in the 1980s and ’90s. But this century, Chris Christie is an outlier. At the federal level, both of its senators have been Democrats since the ’70s, discounting appointments to fill vacated seats; this includes Bob Menendez, who comfortably won reelection last week despite spending the latter half of his term being prosecuted by the Justice Department for corruption.

Still, until recently, New Jersey had a tradition of sending some Republicans to Washington. With the exception of 2008 and 2016, it elected six of them to the House every election this century, with the state having either 12 or 13 seats to fill, depending on apportionment. This was not a national outlier: Winning what one could call “away games”—congressional races on turf mostly populated by voters of the other party—has been a determining factor of who controls the Capitol.

The ability to win such races, however, is fading. It has been for a while. Although tribalism seems like only the topic du jour because of Donald Trump, Congress was becoming more sharply polarized years before he entered politics. Instead, his rise to power correlated with an acceleration of this trend—going from something resembling a crawl to a sprint. Under Trump, this has meant a diminution of Republicans’ ability to win in blue states. But don’t forget that Democrats began having the same problem in red states during the Obama years.

Examining these changes in partisanship requires some parameters and they’re not easily drawn or necessarily intuitive. For example, the Republican revolution in 1994 might seem like a reasonable starting point—it certainly feels like the beginning of our current era. But at the outset of the 103rd Congress in ’95, the South was still pretty hospitable to Democrats. Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee had zero Republican senators. There was one of each party in Kentucky, Georgia, Virginia, and South Carolina. Bill Clinton was a Southern Democrat and did well in the region in the 1996 presidential election, winning his home state of Arkansas, as well as Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, and Tennessee. The electoral map was still morphing enough in the ’90s that it hadn’t yet settled on its current configuration; the near 50/50 election of 2000 is actually much closer to the mark. So let’s use that as the outer bound.

Counting 2000, 22 states have voted for the Republican presidential nominee each time this century, and 15 states have supported the Democratic nominee. To simplify a definition, let’s call these America’s “red states” and “blue states.” (We’re going to leave aside Indiana—generally thought of as a red state—and New Mexico—generally thought of as a blue state.)

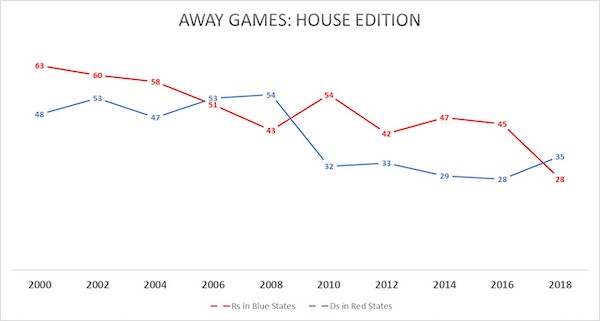

In the 2000 election, there were 63 Republicans elected to the House from states that Al Gore won, and there were 48 Democrats elected to the House from states that George W. Bush won. Those numbers held reasonably steady through the 2006 midterms, when the electoral winds favored Democrats much more than Republicans.

But then 2008 happened.

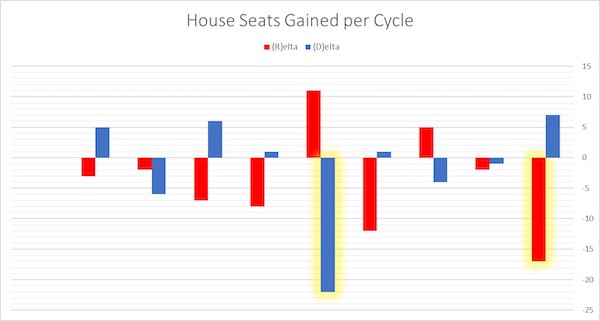

Democrats had peeled back Republican strongholds the last few election cycles, but it precipitated a backlash in 2010 that either really set the country on a path toward polarized politics, or confirmed that it was already there. While this hurt the Obama majority then, the same effect hurt the Trump majority eight years later. Note the highlighted bars in the next chart, which show the most severe “away-game” losses from the previous election for each party in the 21st century. (Let’s call the Democratic change “(D)elta” and the Republican change “(R)elta.”)

These swings appear increasingly extreme, so maybe there are some underlying explanations beyond cultural triggers like right- and left-wing activism and media evolution. Take gerrymandering, for example. The more that state governments rig the game in favor of one party, it makes sense that the opposing party would gain a smaller share of House seats state by state.

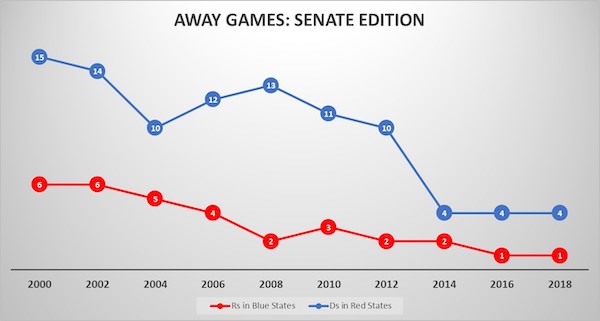

But that wouldn’t explain statewide elections—which is where the Senate comes into play. After November 2000, Democrats held 15(!) seats in red states, accounting for 30 percent of their total. In a chamber divided 50-50, their ability to win in Republican strongholds was crucial. Fast-forward 18 years and their foothold in those same 22 states numbers just 4 seats.

On a percentage basis, this decline is striking: 73 percent, compared to “only” a 27 percent drop in House incumbencies in red states over the same period.

Although Republicans have had to defend much less territory outside red states, it’s notable—if not alarming—that they only have one Senate seat in an Obama/Clinton state. That would be Maine’s Susan Collins, who Democrats have begun to single out for her support of Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the Supreme Court.

Both parties have become less adventurous over the last 20 years, preferring to defend home field and run up their numbers there. It’s addition by retraction.