Rep. Kevin McCarthy is a people person. He makes a point to remember details about his fellow House members, such as the names of their spouses and kids and their birthdays. “There is nobody better at understanding all the members and where they come from,” Jason Chaffetz, a former congressman from Utah who retired last year to become a Fox News contributor, tells me. The California Republican might be adept at the small gestures that can win people over, but as his failed bid to replace former speaker John Boehner in 2015 proved, those attributes are not necessarily enough to win him the speakership.

When House Speaker Paul Ryan announced this spring that he would be retiring after nearly 20 years in office, the Wisconsin Republican was quick to anoint McCarthy as his preferred successor. “I think we all believe that Kevin is the right person,” Ryan told NBC, arguing that McCarthy had gained much-needed experience as the majority leader since his first attempt to fill the job. But McCarthy finds himself today in a perplexing spot—if not a more challenging one—than he was in three years ago. Not only could the conservative House Freedom Caucus deny him the speakership amid policy disagreements as they did last time, but the approaching midterm elections in November could rob him of the opportunity altogether if Democrats retake the House.

Chaffetz, who challenged McCarthy for the speakership in 2015, shares his thoughts about the current leadership race during a phone interview. “I was concerned the Republicans didn’t have a choice,” he says of his decision to run. “I didn’t think I could necessarily win, but I also felt like we needed a choice. At the time, we didn’t want to just simply promote everybody in leadership.” But that’s exactly what the Republican conference appears poised to do this time around. Chaffetz does see benefits in a potential McCarthy speakership. “He’s one of the hardest-working people. He raises an exceptional amount of money,” Chaffetz tells me. “But there are others that are going to differ with him on a lot of policy issues. I think those are legitimate concerns.”

Chaffetz is referring in part to the roughly three dozen members of the Freedom Caucus who are withholding their support until they can negotiate better representation for their caucus members on key House committees and more influence on the legislative process. Whether they will support McCarthy is an open question, but his close relationship with President Donald Trump could easily factor into the decision.

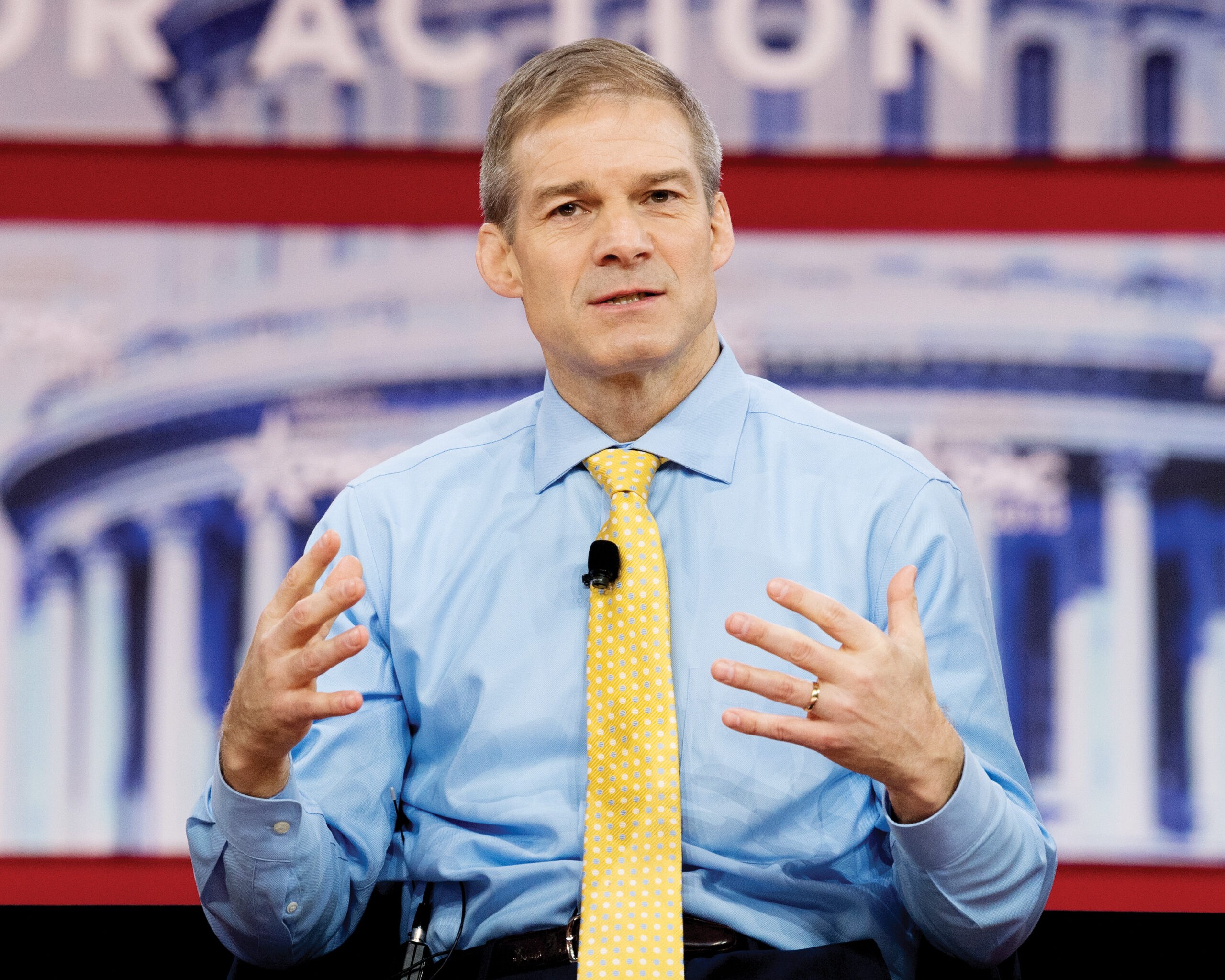

Some conservatives, like Michigan’s Justin Amash, don’t appear willing to consider McCarthy at all. “He hasn’t earned the trust to be speaker of the House,” Amash tells me. And Kentucky libertarian Thomas Massie argues that any member who supported the recently passed $1.3 trillion omnibus spending bill should automatically be out of the running. “If you followed this leadership off of that cliff,” Massie says, “then you are not qualified to lead us around the next.” As well, it doesn’t help McCarthy’s cause with conservatives that Ohio Republican and founding Freedom Caucus member Jim Jordan is seriously considering a run.

Chaffetz doesn’t offer a clear answer as to how he would vote if he were still in the House. He says his decision would depend on who else chooses to run, but he notes that McCarthy has done a lot to support Republican candidates on the campaign trail. “I’m not anti-Kevin McCarthy,” he hedges. “I just feel like there should be a choice and there really ought to be a dialogue around where we’re going and how to do things better.”

McCarthy’s first attempt at the speakership failed due to a combination of conservative opposition, a gaffe about the Benghazi investigation that drew criticism from fellow Republicans, and rumors of an extramarital affair (which McCarthy denied). When he dropped out of the race, McCarthy argued that Republicans needed a “fresh face” in order to unite. At the time, then-presidential candidate Donald Trump took credit for McCarthy’s failure. “You know Kevin McCarthy is out, you know that, right?” Trump said at a campaign rally, to cheers from the audience. “They’re giving me a lot of credit for that, because I said, ‘You really need somebody very, very tough and very smart.’ ”

Today, however, McCarthy has established himself as one of the congressional Republicans closest to the president, largely by painstakingly cultivating Trump. He infamously had a staffer sort through a bag of Starburst candies for the red and pink ones (Trump’s favorites) and delivered only those to the White House, the Washington Post reported. At one time McCarthy was even rumored to be under consideration to be Trump’s chief of staff if John Kelly were to leave. Some House members view McCarthy’s and Trump’s interests as more compatibly aligned than Trump’s and Ryan’s. “Ryan is the policy wonk, and the president isn’t,” Iowa Republican Steve King told the Washington Post. “The president picks up on Kevin being a different kind of guy,” he added. During interviews with members and staffers who have worked with McCarthy, the Californian receives high marks for his political chops and personal skills, but many worry that his knowledge of policy is lacking.

House members might be concerned about McCarthy’s familiarity with policy, but the president is not. In fact, Trump has expressed support for the idea of pushing Ryan out of the speakership before November in order to hand the gavel over to McCarthy. As The Weekly Standard first reported on May 20, McCarthy and his allies weighed the prospect of pressuring Ryan to leave sooner, arguing that triggering a vote on the speakership before the midterm elections would compel Democrats to vote for (or against) Nancy Pelosi for the position, which could be used against them on the campaign trail. The president liked the idea when he was told of it but has not made a final decision about how to act, a source close to the conversations tells me.

White House press secretary Sarah Sanders left the question open when asked on May 22 whether Ryan should stay through the midterms, saying, “At this point that’s something for Speaker Ryan and members of Congress to make that determination.” Behind the scenes, though, the notion of Ryan leaving sooner has won support within the administration. Office of Management and Budget director Mick Mulvaney endorsed the idea at a Weekly Standard summit in Colorado Springs last week, admitting he had spoken to McCarthy about it in private. “I’ve talked with Kevin about this privately but not as much publicly,” Mulvaney said. “Wouldn’t it be great to force a Democrat running in a tight race to have to put up or shut up about voting for Nancy Pelosi eight weeks before an election? That’s a really, really good vote for us to force if we can figure out how to do it.” Mulvaney’s spokesperson later said he was speaking hypothetically.

McCarthy denies ever speaking to Mulvaney about the issue, but he did feel compelled to publicly fall in line with Ryan, saying that a leadership election should not happen until November. “Paul is here until the end of the election,” he told reporters on May 21.

Some Republican House members speculated about why McCarthy might want to circumvent a drawn-out speaker’s race. “Common sense will tell you the longer any race goes on, the more potentiality you have for different people or different stories or different events or different problems that could arise,” a Republican lawmaker tells me.

And McCarthy is keenly aware of one looming issue rife with possible obstacles: immigration. Within the party, debate rages over the funding of Trump’s promised border wall and the future of nearly 700,000 unauthorized immigrants who were brought to the United States as children (under the program known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA). Led by south Florida Republican Carlos Curbelo, some members have filed a discharge petition to force a vote on four separate immigration measures. The so-called “Queen of the Hill” process would allow for the bill with the most support (above the threshold to pass) to move on to the Senate. The Republican leadership in the House worries that such a process would lead to a more liberal immigration package passing the chamber, which the president would likely refuse to sign. “I would like to have an immigration vote before the midterms. But I want to have a vote on something that can make it into law,” Ryan said during a press conference after the discharge petition was filed, perhaps failing to remember that in remarks to a bipartisan group of lawmakers in January, Trump promised to sign whatever Congress presented to him. “I am signing it. I will be signing it. I’m not going to say, ‘Oh gee, I want this, or I want that.’ I will be signing it,” Trump said.

Sensing the hazards of an internecine struggle over immigration, McCarthy would like to bypass the conversation altogether. “If you want to depress [GOP voter] intensity, this is the No. 1 way to do it,” McCarthy told members during a recent conference meeting, according to Politico’s Rachael Bade and John Bresnahan.

For now, Ryan is promising he will bring up immigration measures for consideration in June to placate centrists who want to see long-awaited movement on the issue. For most members, however, as the same Republican lawmaker tells me, “the big question is can we sustain the status quo for the next five months?”

“That’s going to be challenging because there are some that would like to see Paul go even now.” Asked to outline the best-case scenario for the conference, the lawmaker pauses.

“At this point, I don’t see a best-case scenario,” he says.