A warm June night in the foothills of the Amari Valley. The moon is down and the land is dark. Below us, the gorge falls away unseen toward the medieval chapel of St. Anthony and the Minoan cave sanctuary, then down to the coastal plain at Rethymnon, where the lights twinkle around the bay. White light from the taverna’s terrace where we sit spills onto the shade trees and spring of Patsos’s tiny plateia. Behind us, the invisible hills push upward through the darkness toward the pale hump of Mount Psiloritis, from whose southern face the gorges defile steeply into Crete’s rocky southern coast. We cannot see this geography as we sit on the terrace, but we know it is there.

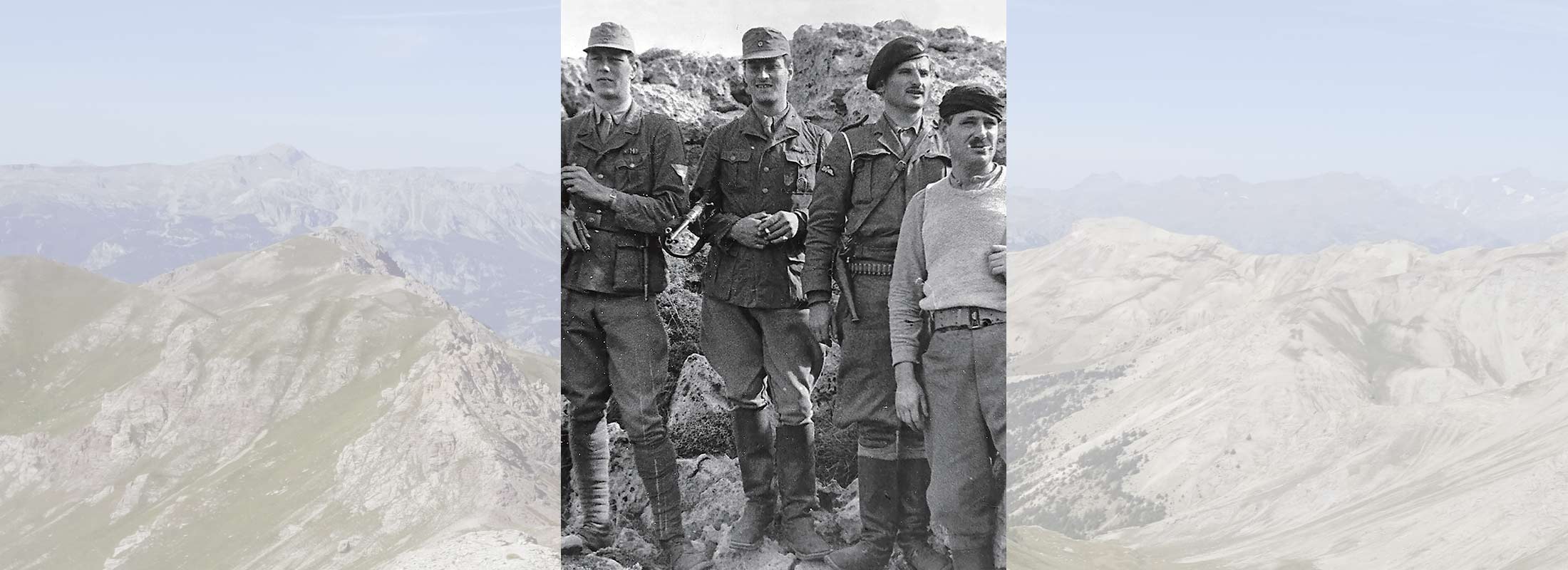

We have come to Patsos in a group from the Patrick Leigh Fermor Society. In April 1944, Leigh Fermor, his fellow Special Operations Executive officer William Stanley Moss, and a supporting cast of Cretan resistance fighters kidnapped General Heinrich Kreipe, the commandant of German-occupied Crete, on the road near Knossos. For 18 days and nights, the kidnappers evaded German search parties and traversed the mountainous spine of Crete—until a Royal Navy launch extracted them and their prisoner from the beach at Rodakino on the south coast. In 1957, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger made a film out of William Stanley Moss’s diary of the operation, Ill Met By Moonlight, with Dirk Bogarde as an improbably dainty Leigh Fermor.

Hundreds of ordinary Cretans assisted the flight of the Kreipe party. Patsos was one of many villages that, risking mass executions and the burning of its homes, protected and sheltered the kidnappers. Our group from the Leigh Fermor Society includes William Stanley Moss’s daughters and granddaughter. They spent the morning tracing the Kreipe party’s escape route along the eastern flank of the Amari Valley. The valley is shaped like an inverted horseshoe, a long loop of mountains around a flat, lush plain. At Fourfouras, a huddle of houses with a café whose pergola is made of the loading rails from German tank transports, an ancient man emerges from a battered Fiat. Stephanos Tsimanderas, now 94, had heard of our party’s approach and driven down from the top of the valley. He shows Moss’s daughters an old photograph of him and his andarte (resistance) friends, all bristling mustaches and British-issue Sten guns. As a teenager, Tsimanderas had aided their father and the Kreipe party when, climbing to the crest at the valley’s southern end, they had seen their escape route, a triangle of blue where two hills slid into the Libyan Sea.

The Amari Valley was a center of Cretan resistance. After the fall of Crete in May 1941, the villagers smuggled hundreds of British, Australian, and New Zealander soldiers to the beaches on the south coast. Over the next three years, British agents and bands of andarte guerrillas harried the Germans from the caves above the villages. In August 1944, as the Germans prepared to withdraw to the coastal plain, they massacred the civilian populations of nine villages. On the way down the western side of the valley, the Leigh Fermor Society stops at the monument at Ano Meros. The bones of the murdered villagers are visible through a glass-doored ossuary. There are bullet holes in the skulls.

“We are now hiding in a delightful spot which is about a mile from Patsos,” William Stanley Moss wrote in May 1944.

Their host, Efthimios Harokopos, allowed his son Giorgios to join the kidnappers on their escape to Egypt. Though his wealth, Moss recorded, consisted of “little more than some goats and a few olive trees,” he refused Leigh Fermor’s offer of gold sovereigns.

Tonight, the same family has honored the Leigh Fermor Society with a banquet at its taverna. Our host, Vasilis Psiharakis, is Giorgios Harokopos’s nephew and a retired colonel in the Greek special forces. The guests include Giorgios’s octogenarian cousin Zacharenia Pattakos, whose parents were murdered in the German reprisals. Dinner is excellent. The glasses are filled with tsikoudia, the paint-stripping Cretan spirit, and Vasilis Psiharakis stands to attention in his immaculate dinner jacket, his mother watching from the doorway of the kitchen.

“Every Greek landscape has a name and an association with memories,” Psiharakis says. “Here, we were disgraced; there, we were glorified. The landscape is soaked with moments of happiness and moments of misfortunes, of sacrifice which, rising by its rigorous course, cannot be escaped. It is a call, and you must hear it. We welcome you with the same feelings of pride and the same warm embrace as we did 72 years ago.”

Toasts are made to Leigh Fermor, Moss, and the andartes, and to the peoples of Crete and Great Britain. The link between the families of Harokopos and Moss, and the link between the Amari villagers and the British visitors drawn here by the terrible epic, would be the stuff of legend—were they not true. Like all living myth, this tale is both prosaic and fantastical. Yet Patrick Leigh Fermor, an accomplished fantasist in prose, was not its author. He polished Moss’s account and also translated The Cretan Runner, the andarte George Psychoundakis’s memoir. But Abducting a General, which collected Leigh Fermor’s own extensive operational reports from 1944 and a similarly detailed narrative of the Kreipe operation written in the 1960s, was not published until 2014, three years after Leigh Fermor’s death.

Chris White, the editor of Abducting a General, is with us at Patsos. White, who retains the genial patience of his upbringing as a Quaker and career as a social worker, is now a full-time battlefield historian, an expert on the caves and high places of wartime Crete. Such is the transformative potential of the memory and myth of World War II. But as Leigh Fermor discovered, mythic transformations are more easily wrought than reversed.

Leigh Fermor bequeathed a literary legend and several captivating and profound memoirs of his journeys across the lost continent of prewar Europe. His writing is evocative, lyrical, and meditative and his books remain popular despite their uncompromising sophistication of style and historical range. But the question of his literary value cannot be separated from that of his cultural standing. Our perception of the past changes over time—as did Leigh Fermor’s—as facts and experiences are layered into memories and myths. To understand the growth of the Leigh Fermor cult, and the enthusiasm that impels people to search out caves and safe houses in the mountains of Crete, we have to excavate across time and space. To begin, we must dig back to 1934, when the 18-year-old Leigh Fermor set out to walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople.

How many English literary writers from the early 20th century remain genuinely popular? Wodehouse and Waugh, certainly. Maugham, though, is almost forgotten, and Conrad is more respected than read. Leigh Fermor produced six full-length books in his 96 years. A Caribbean travelogue, The Traveller’s Tree (1950), which Ian Fleming used as a source for Live and Let Die, was followed by a missable novel, The Violins of St. Jacques (1953). Next came a pair on Leigh Fermor’s visions of Greece, Mani (1958) and Roumeli (1966). Then, with production slowing to a book per decade, Leigh Fermor wrote A Time of Gifts (1977) and Between the Woods and the Water (1986), two of the projected three volumes describing his “Great Walk”—or “Great Trudge,” as he sometimes called it—across Europe in 1934. To fend off his publisher, he also wrote a couple of etiolated memoirs, one on living silently in French monasteries, the other on traveling garrulously in the Andes. Like his correspondence, the short books are the fruit of the most arduous evasion in the field of letters, procrastination by substitution.

Though relatively small, this output suffices to confirm Leigh Fermor as the 20th century’s finest exponent of a genre that the English invented: travel writing. It is a pack mule among literary genres, prone to digression and indulgence but also capable of carrying considerable weight when properly distributed. Leigh Fermor’s picaresques are weighted not just with historical anecdotage, heraldic speculation, and more purple streaks than a sunset at Collioure. They also carry the freight of his generation. When Wodehouse (born 1881) was confronted with the enormities of World War II, he persisted with his Edwardian fantasies and got himself into trouble accordingly. To Waugh (born 1903), the Nazi-Soviet Pact revealed the enemy “plain in view, huge and hateful, all disguise cast off . . . the Modern Age in arms.” When the Soviet Union changed from enemy to ally, Waugh knew that, one way or another, the Modern Age would win. Leigh Fermor was born in 1915. The precocious literary pedestrian was formed by a war that he did not expect to survive.

When Wodehouse was 23 years old, he wrote The Gold Bat (1904), a novel of boarding school pranks involving a miniature cricket bat. When Waugh was 23, he wrote “The Balance” (1926), an experimental story written as a film scenario. When Leigh Fermor was 25, in 1940, he trained as an Irish Guards officer, transferred to the Intelligence Corps, and sailed for Greece. “I had read somewhere that the average life of an infantry officer in the First World War was eight weeks, and I had no reason to think that the odds would be much better in the Second. So I thought I might as well die in a nice uniform.” By the time he was able to get out alive from the war, get out of uniform, and, his derring done, set out again from Britain and return to Greece, he was 31 years old.

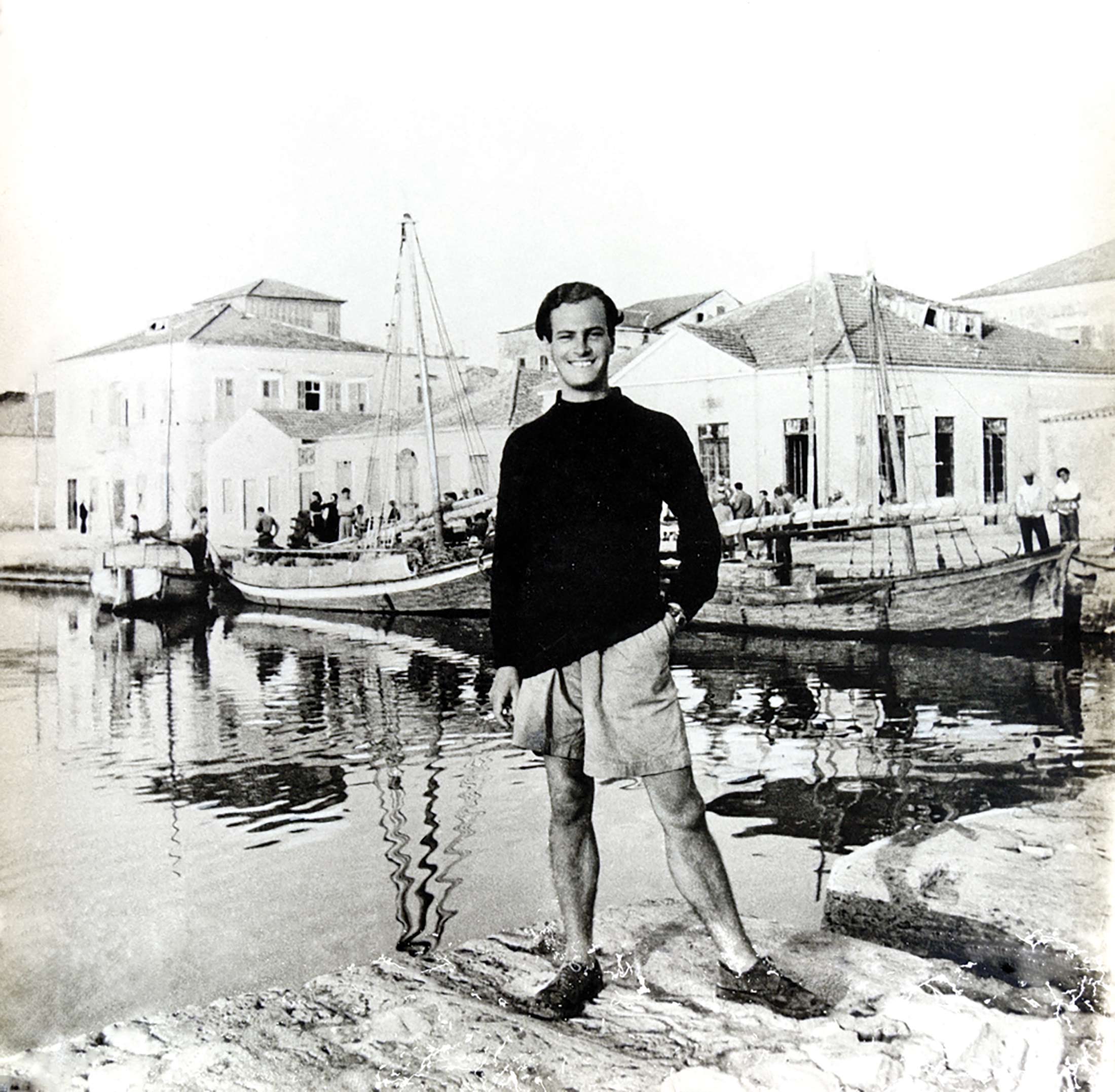

“The clock has suddenly slipped back ten years, and here I am sitting in front of our café in the small square, at a green-topped iron table on one of those rickety chairs,” he wrote to his prewar lover Balasha Cantacuzène from the island of Poros on the day before Easter 1946. “The marble-lantern, with its marine symbols—anchors and dolphins—is within reach of my arm; the drooping tree has been cut down. But the same old men, in broad, shady hats, snowy fustanellas [traditional skirt-like garments] and moustaches, sit conversing quietly over their narghilehs. They all bowed and greeted me warmly, but soberly as if I had seen them only yesterday.”

On Easter Sunday, he crossed the strait from Poros to the harbor at Galatas. He climbed up through the lemon groves to the mill where he and Balasha had lived before the war. Their hosts had prepared a feast “under the vine-trellis—paschal lamb and retsina.” Below the mill, he wrote to Balasha, “our amphitheatre of orange and cypress and olive wavered down to the glittering sea and the island.” Everything was as it should be, but nothing was the same. Balasha, trapped in Russian-occupied Romania, would shortly be immured behind the Iron Curtain. And Leigh Fermor, though he did not mention it in his letter, had fallen in love with the photographer Joan Eyres Monsell.

This letter anchors A Life in Letters, first published in Britain as Dashing for the Post, and released last year in the United States by New York Review Books, which has been publishing or republishing all his writings, short and long. Adam Sisman, the volume’s editor, thinks it “probable” that Leigh Fermor never sent that letter to Balasha, but wrote it “to make sense of his conflicting feelings.” In 1977, Leigh Fermor substituted a similar epistolary device for a conventional introduction to A Time of Gifts. This time, he addressed his close friend Xan Fielding, with whom Leigh Fermor had shared first the dangers of operations in Crete and then the pleasures of postwar exile as a writer in the Mediterranean.

It was hard, Leigh Fermor wrote, “to believe that 1942 in Crete, when we first met—both of us black-turbaned, booted and sashed and appropriately silver-and-ivory dagger and cloaked in white goats’ hair, and deep in grime—was more than three decades ago.” Both he and Fielding had dropped out of school, walked across Europe, and ended up in the Special Operations Executive because they disliked regular army discipline and happened to know Greek. Hiding in caves among the limestone crags, they had “reconstructed our pre-war lives for each other’s entertainment” and had convinced themselves that “the disasters which had set us on the move had not been disasters at all, but wild strokes of good luck.”

In Leigh Fermor’s books, memory is layered over speculation and digression patched over confession. Many passages are so overworked that the planes creak and sag beneath their own weight. This florid sensuality marks Leigh Fermor as a delayed Edwardian—an unacknowledged heir to Norman Douglas, who first applied the Modernist method to travel writing in Siren Land (1911) and Old Calabria (1915).

In his letters, Leigh Fermor’s voice is clearer. The phrasing is crisper, the relish for books and gossip more pungent. He might be a better writer over the sprint than the marathon: A Life in Letters confirms him as a late champion of epistolary form. But the conflicts of his character are more visible too. He is a charmer, a lover of books and women but, as in Crete, he is infiltrating a society under assumed identities. He hides in plain sight, a social climber singing for his supper. He is split between his art and his life.

In February 1960, he is supposed to be writing a book at Chagford, the small hotel where Evelyn Waugh wrote his novels. Instead, he expends his energies hunting on Dartmoor and corresponding with Ian Fleming’s wife, Ann. The master of the local hunt is “Chas Hooley, a tremendous s— with carrot-coloured hair and side whiskers.” Hooley leads Leigh Fermor on “shaggy, almost prehistoric helter-skelters” over “a rolling moor beset with bogs and tors and druidical stones” so ancient that “we might almost be out after dinosaurs.” On one hunt, the only other follower is “Bunny” Spiller, scion of the Spillers Dog Biscuits dynasty. On a second excursion, Leigh Fermor dismounts in order to inspect the rood screen in a “lovely late Plantagenet church.” On a third, he gets lost “in mist, rain, rocks and swamp” miles from anywhere. A “drenched elderly, chubby and equally lost horseman” turns up. They trot home in the rain, the other man reminiscing about “embassy life in St. Petersburg, Constantinople, the Atlas Mountains” and complaining about “the absurd prices that Fabergé cigarette cases fetch nowadays.” Their paths fork at a dolmen: “We said goodnight with gravely doffed headgear.” The other rider is Harold Nicolson’s brother, Frederick, Baron Carnock.

Leigh Fermor did love a lord. He positively adored a lady. Somerset Maugham called him a “middle-class gigolo for upper-class women”; among his regulars were Diana Cooper (23 years his senior) and Ann Fleming. Even Joan, his longtime companion in the simple life and eventually his wife, was a viscount’s daughter. “I do believe my snobbish days are over,” he tells Joan after a night out with various Sitwells in 1952. Really they are just beginning. He cannot hear a name without dropping it or see a shoulder without rubbing with it. In 1954, he tells Diana Cooper that discovering that his new friend is the great-great-nephew of Sydney Smith sets his “historico-snobbish fibres a-tingle.” Around this time, he befriends Deborah, Duchess of Devonshire, the youngest of the Mitford sisters. Christmases ensue at the Duke of Devonshire’s palace, Chatsworth.

“It’s lovely here,” Paddy writes to Balasha from the library at Chatsworth at Christmas 1975. Sybil, the Dowager Duchess of Cholmondeley, is staying. Diana Cooper says that Sybil, who is Philip Sassoon’s sister, had an affair with the French actor-director Louis Jouvet. Everyone has gone for a walk, apart from Paddy and “Uncle Harold”—Macmillan, that is. “He’s sitting beside the fire now, leaning back with long legs outflung, reading Thomas Hardy’s poetry, the book held almost touching his nose, occasionally reading out a few lines—‘Rather good, eh?’—when I break off this letter for a minute or two’s chat.”

Leigh Fermor worked harder at his act than his writing. The interests that enrich his books—heraldry, defunct royal houses, literary gossip—become the higher gossip of his letters. In his correspondence with “Debo” Devonshire, he plays the court jester. Both remain lodged in the slang of the 1930s. Life can get “beastly” and “queer,” but most of the time it’s “ripping” and “smashing.” He sends her inscribed copies of each of his books. “Look here, honestly, it’s awfully good,” he says. “All right, Pad, I will try one day,” she replies. But she never does. He wastes his talent on his intellectual inferiors because they are his social superiors. His good luck—survival as a war hero—has turned into disaster, entrapment in the role of courtier. But the world is not the same as it was before the war, and he is too dashing for the post.

In 1944, when Leigh Fermor was in the Amari Valley, Evelyn Waugh, a veteran of the earlier Battle of Crete, retired to Chagford to write Brideshead Revisited. “I took you out to dinner to warn you of charm,” Waugh’s aesthete Anthony Blanche tells his social-climbing protagonist, Charles Ryder. “I warned you expressly and in great detail of the Flyte family. Charm is the great English blight. It does not exist outside of these damp islands. It spots and kills anything it touches. It kills love; it kills art; I greatly fear, my dear Charles, it has killed you.”

Joan Eyres Monsell was born in 1912, three years before Leigh Fermor. A skilled, self-taught photographer—a collection of her pictures, edited by Ian Collins and Olivia Stewart, is published this month—she broke with her family and mixed with the smarter end of Bohemia. In 1939, Joan married a boozy journalist named John Rayner, who had shaped the tabloid style of the Daily Express. She wanted an open marriage; he did not; they broke up during the war. “Do you really want to start our same old life again?” Joan asked Rayner in a letter from 1943.

Joan and Paddy met in Cairo in late 1944, when she was working as a cipher clerk and he was recuperating after the Kreipe kidnapping. In late 1945, he pursued her to the Athens office of the British Council. Simon Fenwick’s Joan: The Remarkable Life of Joan Leigh Fermor (2017) is another hefty slice of Fermoriana—and an important corrective to the legend. Joan was a freer spirit than Paddy, less dependent upon the attention and approval of others and much less sentimental about everything, except cats.

“I listened in most of yesterday to the Royal Funeral,” Paddy wrote to Patrick Kinross in 1952, after the death of George VI, “and for someone like me who reacts to these things like a scullery maid, it was almost too much—a knot in the throat for almost 6 hours on end.”

“For me, it doesn’t make the slightest difference materially to life here,” Joan wrote to Paddy that week. But it was “maddening” that the BBC’s idea of mourning extended to cutting the scherzo from Vaughan Williams’s Fourth Symphony: “what balls.”

Reading Joan’s biography, I wondered if, without her, Leigh Fermor would ever have managed to extract any art from his disordered life. The legend of Leigh Fermor tends to obscure the fact that it was Joan’s money that kept him afloat throughout their decades together. It was her need for stability that pushed them to find a home in Greece and her inheritance that allowed them to buy a plot of land and build a house at Kardamyli in the southwestern Peloponnese. And it was her prewar friends who became his postwar friends.

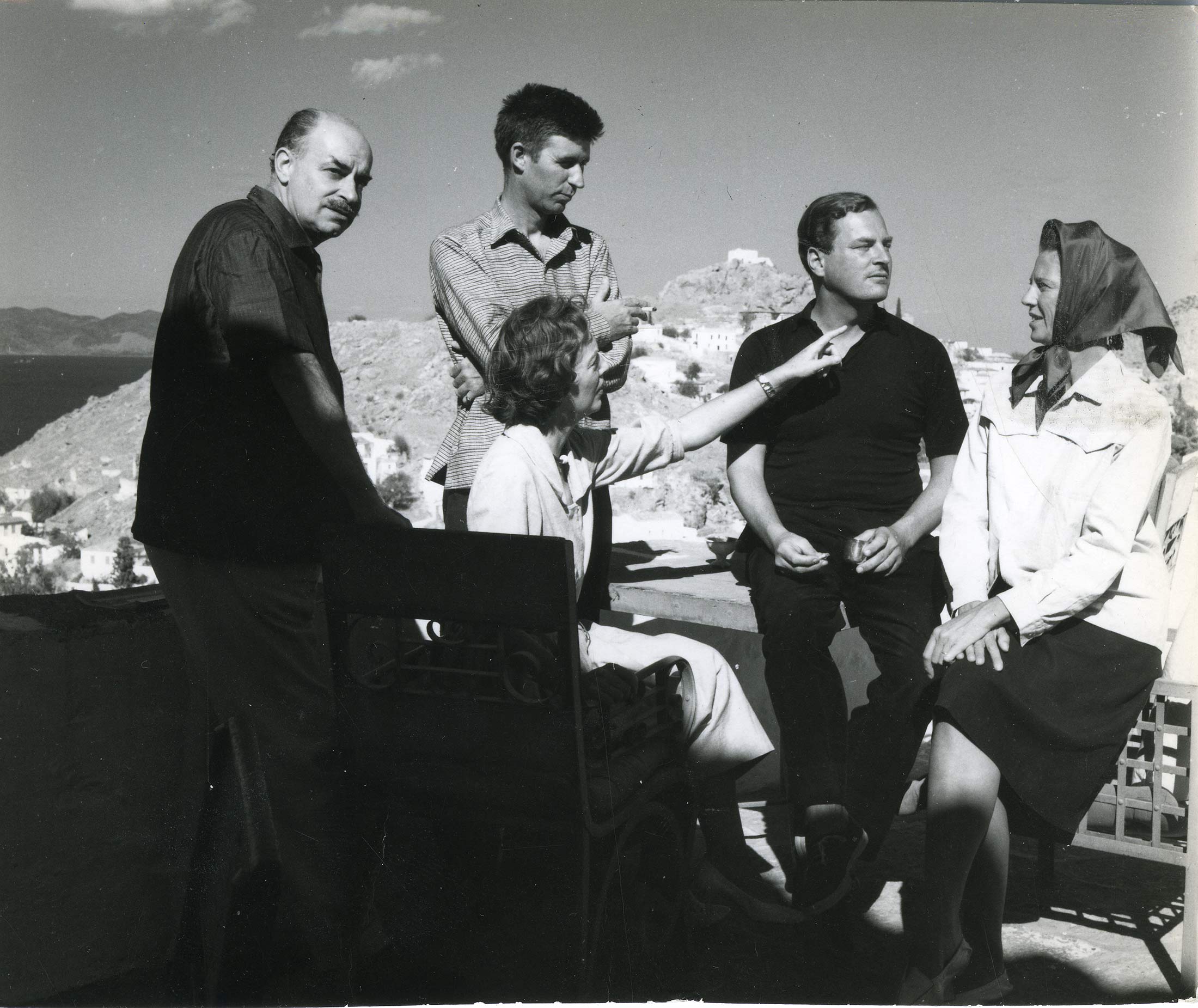

The contribution of friends to Leigh Fermor’s writing and thought is a subject explored in an exhibition now at the British Museum. Charmed Lives in Greece: Ghika, Craxton, Leigh Fermor explores the Leigh Fermors’ friendships with two post-Cubist painters, Niko Ghika and John Craxton. Along with Barbara Rothschild (who would become Ghika’s second wife) and Lucian Freud, they formed a close circle of friends starting in the 1940s and early ’50s.

Ghika, an admiral’s son from the Greek island of Hydra, had absorbed Modernist painting in Paris and returned to Athens in 1934 to become a key figure in the “Generation of the Thirties.” These artists and writers created a specifically Greek style of Modernism. They believed in the continuation of Hellenism through Byzantine civilization and folk art, and recognized the resemblance between Byzantine art, with its flattened picture plane and rocky Greek landscapes, and the shortened perspectives and jagged geometry of Picasso. And had not Picasso drawn upon the Cretan master El Greco, who, before taking up the brush, had worked as a butcher in the market at Heraklion?

While Ghika pushed outward—from Greek history toward international Modernism—Craxton dug inward. The son of an English musician, Craxton’s early work was associated with Neo-Romantic painters like Paul Nash and John Piper, who were doing for the English tradition what Ghika and his friends wanted to do for the Greek. Craxton’s line was formed in London, but his color was transformed, as every visitor’s eye is, by the merciless clarity of to phos, the Greek sunlight. He settled by the harbor at Chania in Crete, grew a shepherd’s mustache, and was unfairly overlooked by the London galleries.

While Ghika and Craxton were painting, Leigh Fermor was writing. Given readers’ fascination with Leigh Fermor’s style, it is surprising how little attention has been paid to its sources. One influence was the 19th-century French novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans, who could elaborate a descriptive passage over several pages and turn lists into composite images; Huysman’s work had a “profound effect” on Leigh Fermor, according to biographer Artemis Cooper. But the influence on Leigh Fermor of Greek Modernism was arguably greater—from Constantin Cavafy to the Generation of the Thirties.

In the fifties, Leigh Fermor wrote Mani at what he called Ghika’s “perfect prose-factory,” his house on Hydra with its views of the Gulf of Argos. Craxton stayed there, too (as had Henry Miller before the war). The house burned down in 1965, but when I climbed over the wall a couple of years ago, the arch of Ghika’s studio was still there among the overgrown fig trees. When I asked the locals about the fire, I was told that a servant had torched the place because she was jealous of the new Mrs. Ghika or that a wild orgy had got out of hand. A letter from Craxton in the exhibition clears up the record: The Ghikas were away and their watchman got drunk and fell asleep in bed with a cigarette.

Leigh Fermor’s deep and unique immersion in Greek Modernism is laid out in a brilliant essay by Joshua Barley in the Leigh Fermor Society’s privately published magazine, the Philhellene. Barley invites us to consider Leigh Fermor’s descriptions of a visit to Ghika’s house, first in a 1957 Encounter article and then in the 1958 book Mani. The steps to Ghika’s house are “collapsible rulers” and the surrounding houses “a chaos of angles.” The landscape is “geometrical,” and the light plays “conjuring tricks.” These are the principles of Greek Modernism, laid out by Ghika and others; they are the invisible geography behind Leigh Fermor’s vision of Greece.

“It is a striking fact,” Barley writes of Mani, “that almost all of the most memorable parts of the book—the flights of fancy, the dolphins, the reminiscing about the War, the description of Gladstone—are to be found neither in the previous drafts nor in the notebooks of the journey itself in the Mani.” Nor is the famous scene in which Leigh Fermor convinces himself that the fisherman Strati Mourtzinos is the heir to the lost throne of Byzantium. Leigh Fermor’s notes from his first visit to Kardamyli could be from a postcard. “Nice hotel. Socrates Phalireas. Comfortable beds, pillows unlike usual cannon-balls. Hist. of Kardmyli. Lawyer, school-master. Sleep. Tour. Then off to Areopolis next day, bathe.”

In the elaborations of the finished text, however, he compresses the weight of Greek history and myth onto the vehicle of travel narrative. The past lives beneath the surface of reality, just as Orpheus, Achilles, and Zeus appear from the dust of a museum floor at Sparta when the caretaker douses the mosaic in water. Leigh Fermor would later explicitly compare “thinking hard about a particular place in one’s past” to pouring water onto a dusty mosaic. With contemplation, regression, and corroboration by “a few old letters” and diaries, all becomes “clear in the end.”

So Leigh Fermor did not dissipate all of his prodigious imaginative energy in socializing. While Ghika was returning Cubism to its origins, Leigh Fermor was carrying that Modernist Greek synthesis back into the English-speaking world. Craxton too was making the same circuit. For the cover of Mani, Craxton offered an abstract painting of the island of Hydra. The sea and sky are flattened against the vertical. The sun is a solar eye emitting black rays.

In Civilization and Its Discontents, Sigmund Freud writes that some mental impressions, like those of early childhood, are “effaced or absorbed”—but that most are obscured by distortions of memory. Under the right circumstances, notably “regression,” the original impressions can be revealed. “This brings us,” Freud writes, “to the more general problem of preservation in the sphere of the mind.” Freud uses the analogy of Rome. A visitor cannot see the earlier layers of Roman civilization, but his guidebook tells him where they once were. This knowledge allows him to ponder a fragment and imagine an entirety or to see a building and locate a now-invisible one. Looking at the Colosseum, we can contemplate the vanished Golden House of Nero. In Between the Woods and the Water, the older Paddy looks at the waters of the Iron Gates Dam and contemplates his younger self, who visited the Turkish island of Ada Kaleh, since drowned beneath the waters.

The problem, Freud writes, is that the workings of memory are incompatible with reality. A single physical space cannot hold “two different contents.” If it did, Freud observes, then the Palazzo Caffarelli would occupy the same spot as the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus and the temple would be visible in both its earlier, Etruscan form and its late, imperial form. But the “phantasy” of memory easily condenses multiple historical images into a single and timeless imaginary space—a myth.

In the final scene of A Time of Gifts, the older Paddy leaves his younger self on the bridge at Esztergom, “meditatively poised in no man’s air”—between Czechoslovakia and Hungary, and between past and future—then constructs an elaborate fantasy of the people of the medieval city preparing for the nocturnal procession that marks Holy Saturday. The phrase “no man’s air” evokes the military metaphor of “no man’s land,” suggesting the tragic future that the younger Paddy did not foresee; the richness of the fantasy is the erudition of the older Paddy superimposed on his unknowing younger self. The original mental impression has been effaced by its reconstruction.

After that kind of reconstruction, Freud thought, the original impression cannot be recovered. This is what happened to Leigh Fermor and most of the material intended for the final installment of his Great Trudge trilogy.

The third part of the trilogy was actually the first to be reconstructed on paper. In 1962, Leigh Fermor turned a commission from Holiday magazine for 5,000 words on “The Pleasures of Walking” into “A Youthful Journey,” a full-scale imagining of his walk from the Iron Gates to Constantinople, written entirely from memory. In 1965, Leigh Fermor set aside “A Youthful Journey” unfinished, first to build his house at Kardamyli and then to write the whole walk saga from the beginning. Also in 1965, he saw Balasha Cantacuzène again and recovered from her the “green diary” that narrated the final leg of the walk.

In the decades that followed, he just could not pull it off. The difficulties were not just those of age, creeping blindness, and an expectant public. Leigh Fermor could not reconcile “A Youthful Journey” with the facts of his green diary. The third volume only came out in 2013, two years after his death, under an apology of a title, The Broken Road.

Artemis Cooper and Colin Thubron, editors of The Broken Road, wonder if the “callowness” of the green diary “jarred with the later, more studied manuscript” of “A Youthful Journey,” or whether the “factual differences disconcerted” Leigh Fermor: “The two narratives often diverge.” The soldier who worked with disguise and subterfuge became the romancer who masked youthful adventure in the garb of myth. Leigh Fermor had already absorbed his youthful impressions, had already effaced them as he reconstructed them in “A Youthful Journey,” had already covered the truth in a performance of which his writing was only one facet. The waters had clarified the mosaic, then obscured it as surely as the waters that buried the submerged island of Ada Kaleh. “Progress has now placed the whole of this landscape underwater.”

* * *

Following the sound of running water in irrigation pipes, I climb through the lemon grove up to the mill above Galatas. The miller’s house is derelict, its roof smashed by a rock fall. The trellis has vanished. A fig tree has erupted through the floor of the hut where Paddy and Balasha lived before the war. A monstrous vine has forced its way up the hollow tree trunk that dropped the water onto the mill wheel. At the foot of the trunk, the machinery lies collapsed and rusted. Across the strait, Poros looks much the same as it did on Easter Sunday 1946, that “amphitheatre of orange and cypress and olive wavered down to the glittering sea and the island.” Everything is as it was, and nothing is the same.

In The Day of the Scorpion (1968), Paul Scott suggests how an impartial observer might see the architecture of the British Raj and the climacteric of the British Empire in World War II:

The further World War II recedes in time, the sharper the edges of its essential contours become. Patrick Leigh Fermor’s books and letters are strung across time’s abyss, skeins that still connect the English to themselves even as the rope runs out. He was one of the last Englishmen. This, and not his esoteric reworking of Greek Modernism, is what explains Leigh Fermor’s posthumous growth from popularity to eminence, from heroism to myth. As Vasilis Psiharakis said after dinner at Patsos, “The sincere feelings of friendship and unity remain unchanged, and serve as a bridge for the principles and values they embody.”