On Christmas

A Seasonal Anthology

edited by Rosie Heys

Notting Hill Editions, 166 pp., $18.95

As one popular theory goes, Charles Dickens deserves a lot of blame for popularizing Christmas as a carnival of conspicuous consumption. Ebenezer Scrooge, the iconic miser of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, expresses his spiritual reform by spending himself silly, promoting the profligate principle that Christmas is never really enough unless it’s too much.

But personal restraint, alternately venerated and mocked as central to the character of Dickens’s fellow Victorians, has also shaped our sense of the holiday. Or so we’re reminded by the arrival of On Christmas: A Seasonal Anthology, a collection of yuletide pieces produced by the English publisher Notting Hill Editions and distributed on this side of the Atlantic by New York Review Books.

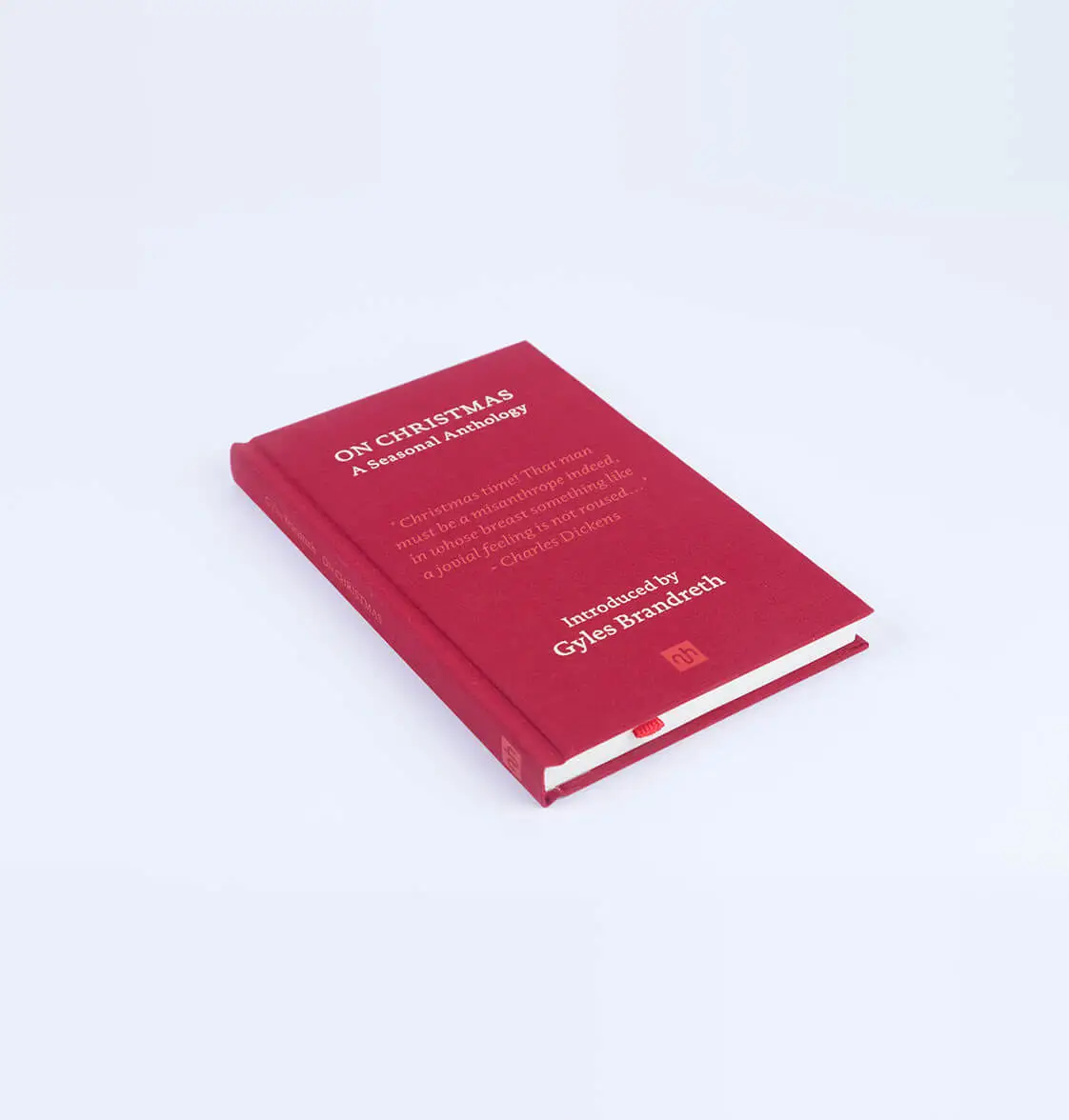

The concept of On Christmas is a model of modesty in the best English tradition. True to other offerings from Notting Hill—a scrappy publisher that specializes in slender volumes of classic essays, as I recently described in these pages—the book is small enough to fit in a coat pocket. Its only nod toward extravagance is its bright red linen cover with a matching crimson ribbon bookmark stitched into the binding. The book looks regal but reserved, not unlike Queen Victoria herself, who makes an appearance as one of the contributors.

Victoria was an enthusiast of Christmas, as Gyles Brandreth, a British polymathic writer, tells readers in a charming introduction. “In 1832,” Brandreth writes,

A December 24, 1833 excerpt from Victoria’s journal is one of the On Christmas selections. “From Mamma I got two lovely side-combs, a stud, a lovely cushion of her own work, annuals, books, prints, handkerchiefs, a lovely cloak, a blue poplin dress, and a pink embroidered dress,” notes Victoria, then a 14-year-old princess. To read the passage is to remember that even in her maturity, Victoria was never a memorable prose stylist. The flatness of her sentences, one gathers, also grew from the notion that even at Christmas, one shouldn’t get too carried away.

That’s why Dickens, who also appears here, would command such a striking presence in Victorian society. For Dickens, whose appeal rested in dramatizing sentiments too vivid for most Victorians to voice themselves, getting carried away was precisely the point—never more so than at Christmas, his grand pageant of feeling.

It’s with Dickens, Brandreth argues, “that our kind of Christmas begins. At least, Charles Dickens is the writer who gives us the kind of Christmas we have decided to love and accept as ‘traditional,’ comforting and cozy. With Dickens, Christmas isn’t a solitary act of worship celebrated by a communicant kneeling at the altar rail, it’s a family festivity celebrated by the hearth and around the dining table.”

On Christmas doesn’t mine from A Christmas Carol, perhaps reasonably assuming that many readers already know it by heart. Instead, we’re given an 1836 essay in which Dickens reveals that even in the 19th century, grumblers were already lamenting that Christmas wasn’t what it used to be. “Never heed such dismal reminiscences,” he urges readers with his usual militant merriment. What follows is a holiday portrait sweeter than a tray of marzipan:

It’s Dickens at his most indulgent, advancing a sense of quick emotional resolution that doesn’t seem earned. In the interest of balance, On Christmas includes a pitch-perfect parody of Dickens by Robert Benchley. “Christmas Afternoon,” though it expertly mimics Dickens’s exclamatory style, renders relatives as they usually are, not as we wish them to be:

Benchley is one of a few Americans included here. Another is Charles Dudley Warner, the 19th-century essayist and social commentator who wondered in 1891 whether we were ruining Christmas by expecting too much from it. “Is anybody,” he asked, “beginning to feel it a burden, this sweet festival of charity and good-will, and to look forward to it with apprehension?”

Like the holiday itself, On Christmas is a mix of frequent delights and occasional disappointments. The pieces are unevenly curated; some selections include an introduction telling us a bit about the author and the work, but others don’t. While a number of the featured writers—Anthony Trollope, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Guy de Maupassant—are widely known, contributors like Sue Townsend will not instantly ring a bell, especially in the States. Townsend, a British humorist who died in 2014 at age 68, has one of the loveliest offerings in On Christmas with “We Can Be Film Stars, Just for One Day,” in which she hints that the holiday’s most abiding pleasures are the small ones. Her working-class family couldn’t spoil her with huge presents, but she “would always be given lots of books from the Woolworths Classic book collection,” Townsend recalls. “It was in these editions that I first read Little Women, Kidnapped, What Katie Did, Tom Sawyer, Jane Eyre, Robinson Crusoe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin etc. I would start to read immediately, breaking off reluctantly to eat my Christmas dinner.”

One theme of On Christmas is that while the holiday nudges us to live in the moment, we don’t get the full measure of the celebration until it’s over. That explains the logic of including a December 31, 1661, entry from celebrated diarist Samuel Pepys. “But my greatest trouble,” he confesses, “is that I have for this last half year been a very great spendthrift in all manner of respects, that I am afeard to cast up my accounts.”

Pepys deftly anticipated what has become, for many, an abiding complication of Christmas—namely the problem, after it recedes, of paying for it.