The U.S. government is emerging from the pandemic on a surprisingly strong fiscal footing but at a greater risk of getting tripped up by bond markets.

On one hand, the federal debt held by the public soared during the pandemic as revenues fell and the government spent trillions to keep businesses and households afloat, from 80% of economic output to just about 100%. That level of debt is the highest since the government financed the World War II militarization effort and is set to grow indefinitely thanks in large part to the baby boom generation aging and being owed retirement and healthcare benefits that are not funded.

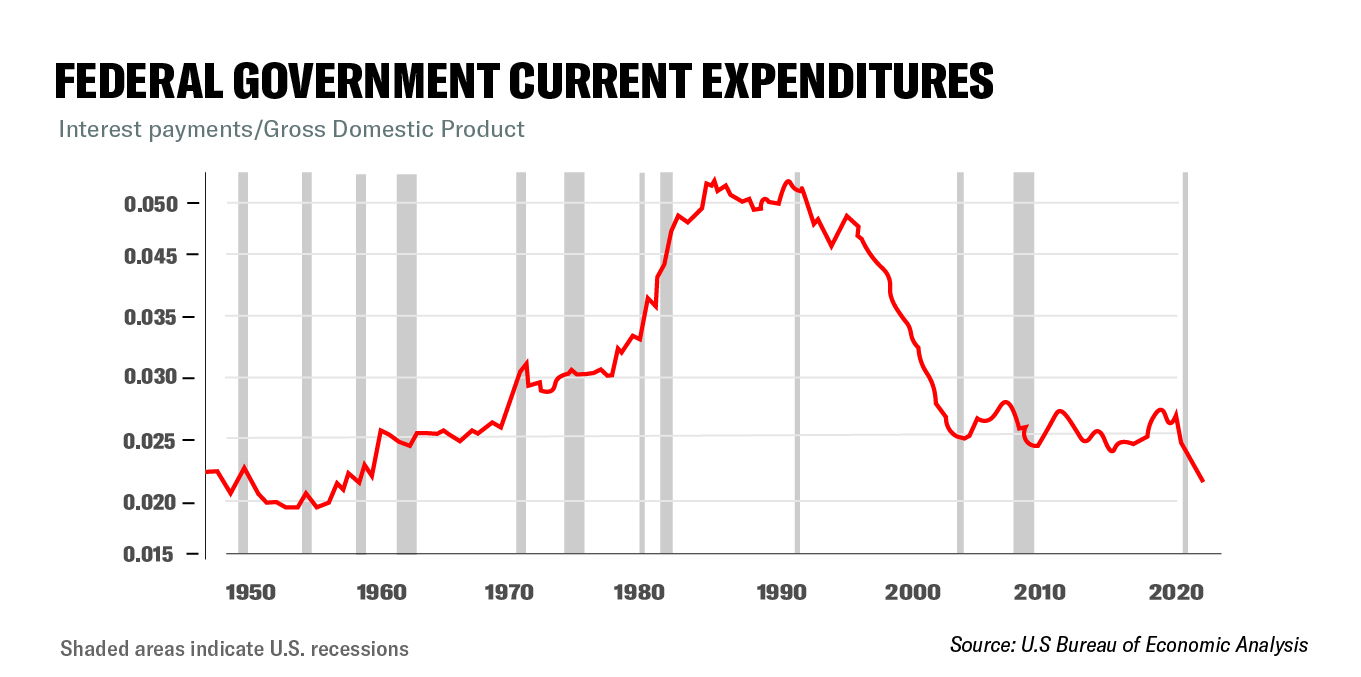

On the other hand, the federal government is spending less on interest on the debt than at any time since 1959.

In other words, although the debt is extremely high and rising, it’s costing the government much less than in the past.

The reason servicing the debt is so cheap is because interest rates have fallen. They’ve fallen in the United States and across the world much further and for much longer than was thought possible. Furthermore, there is good reason to believe that the Treasury will be able to borrow cheaply for a long time — the foreseeable future.

So, the federal government is like a ship that has taken on water and is still leaking slowly. The ship is still moving, and the captain has good reason to believe that he can make it back to port, but the vessel has less ability to maneuver and is at greater risk of going under if it encounters another storm.

“What you have to remember is there probably will be some other economic shock over the next decade,” said Charles Seville, co-head of Americas Sovereign Ratings for Fitch Ratings.

Seville noted that the U.S. has suffered two such massive economic shocks in the past decade-plus: the financial crisis of 2008 and the coronavirus pandemic, both of which led to steep increases in debt. It’s reasonable to fear that it won’t be another decade before the next financial crisis, natural disaster, or war.

Ensuring that the U.S. can handle such calamities without a concurrent debt crisis is reason to oppose President Joe Biden’s plans to ramp up spending, in the eyes of conservative fiscal hawks. One such hawk, Brian Riedl of the Manhattan Institute, calculates that Democrats are aiming to add a total of $8 trillion in new spending over the next 10 years, including the March stimulus, the bipartisan infrastructure bill, the partisan social welfare reconciliation bill, and other proposals.

Even if interest rates stay low, Riedl argues, the Democrats’ planned additional spending will add enough interest costs over the medium term to leave little room in the budget to respond to crises.

And interest rates may not stay low — a possibility that would spell major trouble for the U.S.

The yield on a 10-year Treasury note hovered around 1.5% to start November, historically low.

Yields are expected to rise, slowly, over time, only returning to 5%, about the norm for much of the 2000s, by midcentury, according to the Congressional Budget Office’s latest projections. The office also sees net interest costs for the government rising from an average of 1.6% of gross domestic product over the 2020s to 4% the next decade. At that point, about a quarter of all federal revenues would go to servicing the debt.

Yet it’s easy to imagine interest rates rising much faster. After all, yields on 10-year Treasury notes were above 3% as recently as 2018.

Still, though, there are good reasons to believe that the factors that have driven rates down for the past three decades will persist for years to come.

One such major influence is low expectations for economic growth. Slow growth means fewer investment opportunities, which in turn makes borrowing less attractive to investors at any given rate. Growth forecasts have fallen all over the world, depressing rates.

A related development is the aging of populations worldwide. Economic growth slows as people age out of the workforce, lowering interest rates. Also, as people age, they save more for retirement, increasing demand for bonds and thus lowering rates.

Nor are those trends soon to reverse. Even as baby boomers begin spending down their savings, population aging will exert downward pressure on rates, according to a recent working paper circulated by the National Bureau of Economic Research that disentangled the effects of aging on work and wealth. Hannes Malmberg, a University of Minnesota economist who wrote the paper with economists from Stanford and Northwestern, told the Washington Examiner that “demographics will make it easier to service the existing stock of debt by pushing down on real interest rates.”

So, the Treasury faces what might be a “new normal” of low growth and low interest rates, a scenario that, while far from ideal, does not suggest the risk of a major fiscal crisis is imminent.

Nonetheless, debt dynamics can change quickly. If some sort of shock were to boost interest rates, net interest costs for the government would rise quickly.

“It takes only a small increase in interest rates to bury you,” said Riedl.

The federal debt, unusually for a rich country, is made up of relatively short-term debt. The average weighted maturity of outstanding debt was under six years as of the summer, according to the Treasury, versus an average among developed countries of closer to eight years.

That means that the U.S. government could go from enjoying low interest costs to seeing interest payments crowd its budget in a short span.

“The shorter duration your debt is, the more exposed you are to interest rates rising,” said Seville.