The Supreme Court will consider one of its most high-stakes cases in years on Thursday, one that will have enormous implications for former President Donald Trump‘s efforts to rid himself of a plague of litigation seeking his removal from 2024 presidential election ballots under the “insurrection” clause of the 14th Amendment.

Trump is the leading candidate for the Republican nomination but is facing a major legal hurdle to secure that title in one of the biggest high court cases since Bush v. Gore. A group of Republican and unaffiliated voters in Colorado sued to disqualify Trump from running for office again on the basis that he engaged in insurrection by trying to overturn his loss in the 2020 election and that those efforts led to him “inciting” the Jan. 6 Capitol riot.

The plaintiffs’ case rests on the shoulders of the argument that Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, a Civil War-era constitutional provision intended to keep former officeholders who “engaged in insurrection” from ever regaining power, applies to Trump due to his actions in the final days of his term in office.

Colorado’s Supreme Court made the unprecedented decision on Dec. 19 to agree with the voters who sued to block him from running for president. Just days later, Democratic Maine Secretary of State Shenna Bellows held that state law allows her the power to rule on a similar complaint lodged by Maine voters, and she found that Trump cannot remain on the ballot in response to a lawsuit in that state.

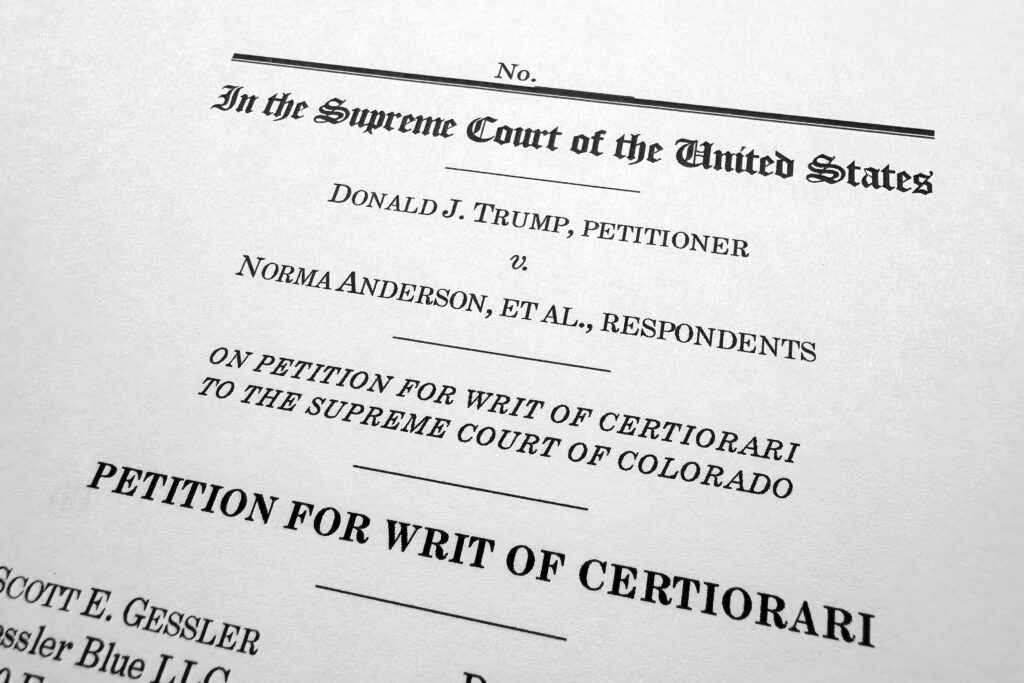

Trump appealed the Colorado ruling, and the case, Trump v. Anderson, has been slated for oral arguments at the Supreme Court on Thursday. The Colorado and Maine decisions have been stayed pending the Supreme Court’s review.

The former president’s attorneys will be allotted 40 minutes for oral arguments, while attorneys for the voters will be given 30 minutes, with 10 minutes allocated to attorneys for the Colorado secretary of state.

While Trump has made a habit out of attending his various legal proceedings spread across various civil lawsuits and four criminal indictments, the former president has not decided whether he’ll be at the Supreme Court, sources close to Trump told the Washington Examiner.

Here are the matters the high court could address during Thursday’s oral arguments:

Who decides ballot eligibility?

Although Section 3 lacks clarity as to whether it can be applied against Trump, it is clear that Congress can restore a person’s eligibility for office through a two-thirds vote. What isn’t clear is whether Congress has anything to say at the beginning of the process — in essence, whether it is “self-executing.”

Trump’s lawyers and legal scholars who embrace their arguments say Congress must act first on the matter of eligibility rather than leave the decision up to the courts, according to their brief.

John Malcolm, vice president of the conservative Heritage Foundation’s Institute for Constitutional Government, told the Washington Examiner there is a “long history” of the 14th Amendment being self-executing when it is used as “a shield to prevent the government from doing something to you that violates your rights” under the amendment.

“As opposed to using it as a sword, you are using this affirmatively to try to force the government to do something, and that when the 14th Amendment is used as a sword, rather than a shield, it requires implementing legislation from Congress, which is lacking here,” Malcolm said.

Conversely, lawyers for the group of voters contend that Section 3 is like any other measure of the Constitution and can be applied without the need for added legislation.

“Nothing in its text or history suggests Section 3 is somehow different in this respect from all other provisions of the Reconstruction Amendments,” according to the plaintiffs’ brief.

The Colorado Supreme Court’s 4-3 majority found that “congressional action is not required to give effect to the constitutional provision,” although dissenters on that same court could not come to the same conclusion. Colorado Supreme Court Justice Carlos Samour said there is an enforcement mechanism for disqualifying someone who is convicted criminally of engaging in insurrection under 18 U.S. Code Section 2383.

“Had President Trump been charged under section 2383,” the justice wrote, “he would have received the full panoply of constitutional rights that all defendants are afforded in criminal cases.”

Is Trump an officer of the United States?

Trump’s lawyers argue that Section 3 is not applicable to him because the president is not an “officer of the United States” and the presidency is not an office “under the United States.”

The 45th president’s legal team points to language in the Constitution that states a president is trusted to “Commission all the Officers of the United States.” In the impeachment clause, there is a mention of the president “and all civil Officers of the United States.” Defense lawyers contend that the term “officers” in that clause does not imply the president is among them.

Voters who sued to keep Trump off the ballot say the Constitution cites the presidency as an “office” at least 20 times and follows that the president is, therefore, an “officer.”

The district court judge who first weighed the Colorado dispute found that Trump did “engage” in insurrection but said the language of an earlier draft of the 14th Amendment included an explicit citation of the “office of the President,” adding in her own words that “certainly suggests that the drafters intended to omit the office of the Presidency from the offices to be disqualified.”

Before the Colorado Supreme Court’s reversal, District Judge Sarah B. Wallace found that while the presidential oath “encompasses the same duties” as an oath to uphold the Constitution, there was a distinction because the oath taken by the president under Article 2, Section 1, Clause 8, “is not the same as the oath prescribed for officers of the United States” under Article 6, Clause 3.

Four justices on the Colorado Supreme Court majority disagreed, saying that the true understanding of “officer” does include the president.

John Yoo, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law, drafted an amicus brief for the Colorado case on behalf of the Claremont Institute that argues there is a distinction between an “elected officer” and officers who are “appointed.”

“The president is an elected officer — is elected — and the Constitution repeatedly distinguishes between the president and the vice president on the one hand, and then officers who are not elected, they’re appointed,” Yoo told the Washington Examiner.

“They’re just separate kinds of positions,” Yoo added.

Within Yoo’s brief, he wrote that Congress’s needed involvement is evidenced through the language in Section 5 of the amendment, which states that “Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provision of this article.”

“But no relevant congressional legislation enabling the states or private persons to enforce Section 3 exists here,” the brief stated.

In a separate legal fight involving Trump, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit found on Tuesday that Trump does not have presidential immunity from criminal prosecution for the alleged act of attempting to subvert the 2020 election, which Trump is likely to appeal to the Supreme Court as well.

The appeals court’s 57-page opinion referenced Trump as an “officer,” though its ruling is not binding on the Supreme Court and won’t affect the way it decides the ballot dispute.

What qualifies as insurrection?

Whether the Supreme Court answers the question of Trump’s culpability for the riot is by far the most political component of the plaintiffs’ 14th Amendment lawsuit and is presumably a thorny subject for Chief Justice John Roberts, who, during a turbulent era in the high court’s favorability, may reasonably want to avoid answering such a question in an election year.

Lawyers for the voters argue that Trump incited the riot at the Capitol during his speech at the Ellipse on Jan. 6, when he encouraged his supporters to “fight like hell” as he called on former Vice President Mike Pence to delay certifying the election in favor of then-President-elect Joe Biden’s victory.

The plaintiffs rely on a report created by the House Jan. 6 committee’s investigation into the riot, while Trump’s lawyers argue the report is one-sided and that Trump, at one point in his speech, called for his supporters to be peaceful, in addition to subsequent tweets with a similar message.

The Colorado Supreme Court nevertheless found that “Trump’s speech inciting the crowd that breached the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, was not protected by the First Amendment.”

Trump’s attorneys state clearly their argument that he was exercising his free speech rights and that he was expressing genuine concerns about voter fraud occurring in the 2020 race despite refutations of fraud by his attorney general at the time, among others.

Professor Vin Bonventre of Albany Law School told the Washington Examiner the “most difficult thing” for the plaintiffs is proving beyond reasonable doubt that Trump had any culpability for inciting the riot.

“I think there’s a bit of a leap going from what the officers of the Confederacy did to Trump inciting some crowd, and then you’d really have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that he intended to incite the crowd, to actually break into the Capitol. And I think that’s the most difficult thing,” Bonventre said.

Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter, writing in dissent of the Colorado Supreme Court’s majority, avoided the merits of the arguments on whether Trump did engage in insurrection but argued such a challenge is one that “no district court — no matter how hardworking — could resolve in a summary proceeding.”

Do all states have to draw the same conclusions for Trump?

The Supreme Court’s final ruling likely won’t look like a perfect match of any number of legal theories that have been debated by scholars, but many observers hope the Supreme Court will rule in a way that will settle the question of Trump’s eligibility with little ambiguity.

“If the court thinks that Colorado is wrong, and Trump has the right to run for office and can’t be disqualified, then it will want him to be able to be on the ballot for the primaries, the majority of which are occurring in March and after. So, there’s a need for the court to act quickly,” Yoo said.

Trump’s attorneys have also raised concerns about the prospects of an inconsistent tapestry of state election ballots, in which some states allow voters to select from certain candidates and not others. Meanwhile, attorneys for the voters say the question is too important to be left undecided and that the plaintext of the Constitution should be applied to everyone, regardless of how much political backing they have.

Some legal experts have raised concerns that if the court fails to decide Trump’s eligibility in a clear ruling, the matter might not be dealt with until Jan. 6, 2025, in the event Trump wins the election and Congress must certify his possible victory. Such concerns include but aren’t limited to “catastrophic political instability” and “disenfranchising millions of voters” who can’t cast a ballot for their candidate of choice.

“A decision from this Court leaving unresolved the question of Donald Trump’s qualification to hold the Office of President of the United States under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment until after the 2024 election would risk catastrophic political instability, chance disenfranchising millions of voters, and raise the possibility of public violence before, on, and after November 5, 2024,” University of California, Los Angeles, law professor Rick Hasen wrote in an amicus brief.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

While Yoo said he believes that “it would be very nice” for the Roberts Court to find unanimity behind its eventual decision, he said, “I wouldn’t expect it happening.” As for when Trump and the nation will know whether he is eligible for the ballot, Yoo said the justices could return a decision “within a month.”

“It’s tough, but they have done it before,” Yoo said.