It’s official. The public faces the worst rerun ever. The same candidates, only even older. Former President Donald Trump, but this time he’s more dictatorial. President Joe Biden, but this time he’s more doddery.

Yet there is a difference, a difference that, though it has gone largely unreported, will be shaping politics when Trump and Biden are remote memories.

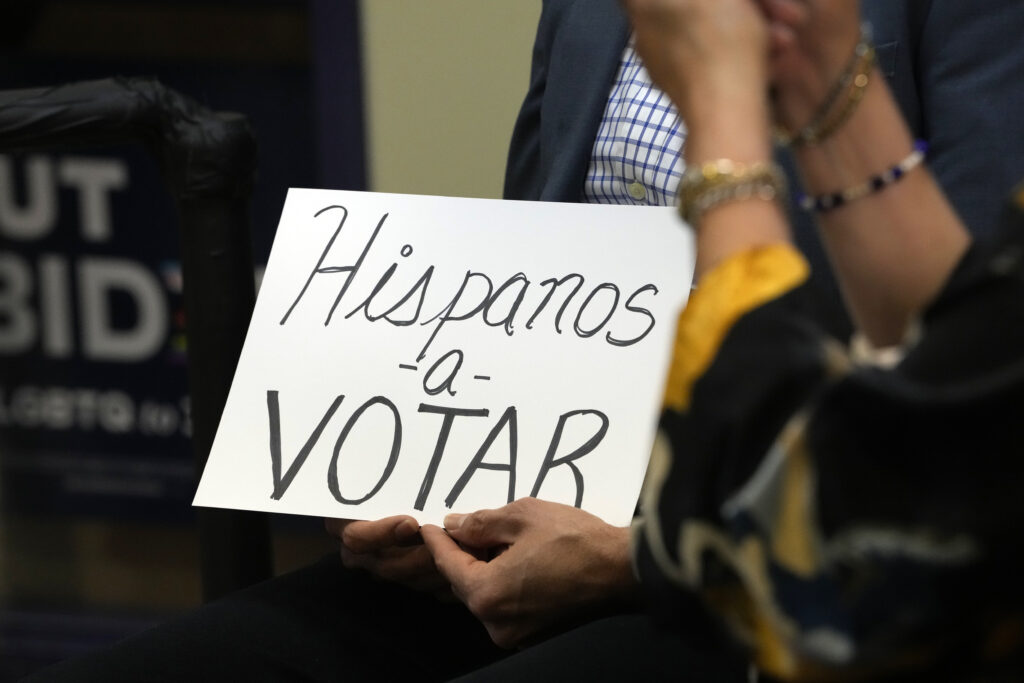

Nonwhite voters have deserted the Democrats. In 2020, Biden was 50 points ahead with minorities. Today, his lead has fallen to 12 points. A poll in the New York Times earlier this month showed Trump leading Biden by 48% to 43%, a surge almost wholly accounted for by Biden’s collapse among black and Hispanic voters.

It is worth pausing for a moment to contemplate those numbers. As recently as 2020, Biden was backed by 92% of black voters. Was that an unusually high number, reflecting his role as former President Barack Obama’s loyal wingman? Not really. Black support for the Democrats had not dipped below 80% since the 1964 Civil Rights Act and was often in the 90s. Until now.

Nor was the New York Times carrying a rogue poll. All the surveys tell a similar story. Gallup finds that the Democrats’ lead with black and Hispanic voters has shrunk by 20 points since 2021 and seems set to shrink further, for it is overwhelmingly younger minority voters who are deserting the party.

What has changed? How has Trump managed to increase his support fivefold among black voters since his last presidential run?

The short answer is that young black people are much likelier than their parents to vote for their values. In a major study in 2020, Steadfast Democrats, Ismail K. White of Princeton and Chryl N. Laird of Maryland asked why, when a third of black voters held broadly conservative positions on tax, guns, and abortion, these views rarely translated into support for candidates who shared them.

Their explanation, to concertina a longer and subtler thesis, was that the experience of slavery and segregation, as well as making race a stronger factor for black people, forged tighter partisan bonds. Political allegiance became part of group identity and was policed accordingly. Unsurprisingly, the most uncomplicated support for the Democratic Party comes from black voters old enough to remember the struggle for desegregation.

Among Latinos, the journey has been more straightforward, though no less dramatic. President Ronald Reagan used to describe Hispanic Americans as “Republicans who don’t realize it yet.” What he meant was that, in time, Latinos would start voting as entrepreneurs, churchgoers, and government skeptics rather than as an ethnic minority that had been arbitrarily placed in the “oppressed” rather than “oppressor” column. And so it has come to pass.

Perhaps we should not be surprised. Hispanic people have followed the same trajectory as other immigrant groups. Eric Kaufmann of Buckingham University, perhaps the foremost expert on the politics of ethnic change, tells me: “Minorities have drifted away from the Democrats as they have become more assimilated, native-born, and residentially dispersed.”

Even so, there is something pleasingly countercyclical about the development. We live in an age defined by identity politics, an age in which every question, from free speech to mathematics, is seen through the prism of race. How refreshing that despite the determined efforts of our intellectual elites to categorize and delimit ethnic identity, the American dream still works its magic.

There is no law that says racial preferences in politics erode over time. Black people were more evenly divided in the 1940s than today.

In Britain — which has, until now, been good at avoiding ethnic politics — the war in Gaza has led to unprecedented divisions. Even the proposal to build a memorial for the Muslim soldiers who fought for Britain in the two world wars (there are already memorials for Jewish, Sikh, and Hindu servicemen) has been politicized, with Nigel Farage tearing into the idea as divisive.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

In a political landscape in which there is little to be cheerful about, the open-mindedness of minority voters is a cause for celebration. For one thing, it is good news for those minorities. When one party takes you for granted, and the other doesn’t even bother trying, your political influence plummets. For another, it is good for standards in public life. The worst examples of complacency and corruption are usually found in places where people feel obliged to back “their” candidates on tribal or sectarian grounds.

Above all, it is good for democracy. If they can’t win on identity, candidates have to win by intellectual persuasion. And that, when representative government is in decline globally, is an unambiguously good thing.