The first truly memorable thing I saw outdoors after three months confined to my house was a Megarhyssa macrurus, or long-tailed giant ichneumonid wasp, depositing its egg inside a rotten log.

I was on Biscuit Brook in the Catskill Mountains’ Big Indian Wilderness, shadowing a friend in search of pocket water, when I came eye to eye with a comically malevolent-looking bug. The size of my thumb, it had yellow antennae, stiltlike yellow legs, a yellow head, and hateful black eyes. From its gleaming black abdomen grew a round, greenish, translucent bladder like a self-inflating raft. I later learned that the wasp’s ovipositor, a trio of black filaments, was also a drill: I’d seen it doggedly boring a hole for the safekeeping of its young. H. R. Giger would have been proud.

That night, I watched a Luna moth swoop into the fire, erupt, and assume its final stage as a burnt tortilla chip. I turned my headlamp to a stagnant pool and tracked poppy seed beetles churning the muck. By daylight, I found slugs laying eggs like tiny clusters of Viognier grapes and caddisfly larvae bricked up like Fortunato in grains of sand.

I felt lucky to witness these miniature dramas, stuff you’d typically get to see only by knowing precisely where and when to look. I’d spent some of the pandemic watching the BBC’s Life in the Undergrowth, and now I was happily sticking my face too close to alien mandibles and stingers in real life. But I knew better than to share these observations with just anyone. Apart from a new parent or a DMT enthusiast, is anyone more smug and insufferable than a nature lover?

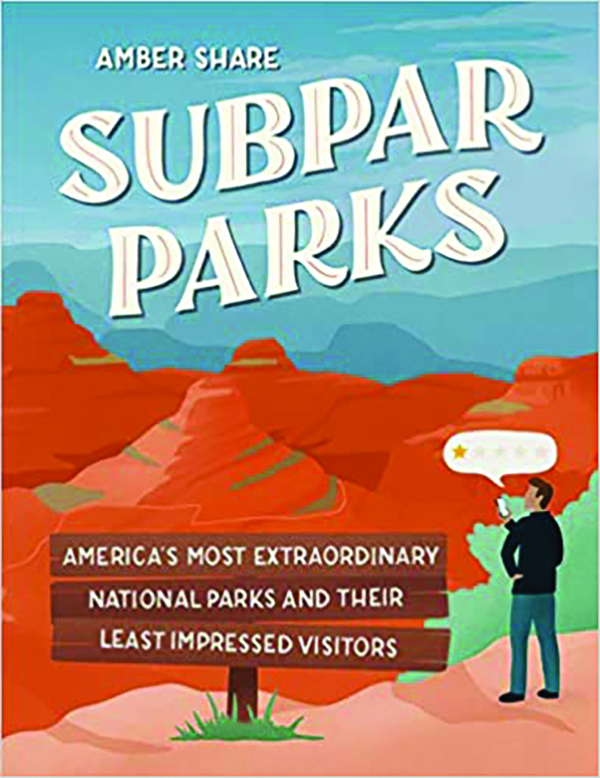

Then again, is there anyone more obtuse and baffling than an unapologetic nature hater? This is the question posed by Amber Share’s Subpar Parks: America’s Most Extraordinary Parks and Their Least Impressed Visitors, an adaptation of a popular Instagram account (358,000 followers), which collects one-star reviews of U.S. national parks. Share, an illustrator and outdoor enthusiast, pairs these breathtaking self-owns with her own simple landscapes, which have something of the stained-glass quality of old WPA posters. The reviews are idiotic variations on Gertrude Stein’s remark about her childhood home, Oakland, California: “There is no there there.”

Of Yellowstone and its Great Prismatic Spring: “Save yourself some money. Boil some water at home.” The Yosemite, represented by its most iconic view of Half Dome and El Capitan, has “too many gray rocks,” and “trees block the view.” (Fact check: false. El Cap rises 7,573 feet above sea level, and at some 3,000 feet from base to summit, it is far taller than the tallest tree in Sequoia, the 275-foot “General Sherman.”) “The only thing bad” about South Dakota’s Badlands “is the entire experience.” If you’d like to see feral ponies on Assateague Island, you will contend with “horse poop on the beach.”

A spoilsport may speculate that these reviews were left in jest. Share insists that she perused their authors’ other output so as not to be fooled. Yet everyone has a friend who counts it a point of pride in his authenticity to “confess” to having been bored by the Grand Canyon (here “a very, very large hole”) or even that Instagram holy grail, White Sands (“literally miles of white sand”). I myself was disappointed by Ohio’s Cuyahoga Valley, which felt in places like an undistinguished suburban rail trail. (On closer inspection: false. Especially at peak foliage season.) No doubt many of the reviews in Subpar Parks are sincere.

Because the joke was bound to wear thin, Share pads her book with park history, activities, rangers’ tips, and quotations from the likes of Enos Mills, John Muir, and Theodore Roosevelt. If the book is slight, it’s still a good compact guide to the park system, an illustrated checklist ideal for children. But it’s also an invitation to feel superior to those who “just didn’t get it” (as one review of Haleakala confessed). Never mind that if this splendor really is self-evident, we shouldn’t demand special credit for appreciating it. If you’re a parent who just drove your offspring several thousand miles to see Bryce Canyon only to be told that it’s “too orange” and “too spiky,” you’re probably less interested in praising your own sense of wonder than in wondering where your parenting went wrong.

Part of the problem is that, in the age of mechanical reproduction, the more beautiful a scene is, the more familiar it is. What the pioneers beheld with virgin eyes looks to the average middle-class child like the default wallpaper on a MacBook Pro. The photography of Ansel Adams, Clyde Butcher, or Paul Nicklen evokes calendars or posters as much as it does actual extraordinary places.

Yet the challenge of turning someone who is indifferent or hostile to nature into the next Helen Macdonald or Robert Macfarlane goes well beyond that. There’s a reason I led this outing with bug talk. In many cases, sweeping scenery is the least interesting thing about America’s wild places. Two reliable ways to spark curiosity about nature are zooming in and zooming out, exploring the processes too small to discern in the panoramic view and those too vast to be contained by it. Animal behavior, plant reproduction, meteorology, seasonal change, and the behavior of light in nature are all more fascinating than a landscape offered without commentary. Gorgeous scenery is often to nature what a pretty face is to a human being. It conceals complexity and personality.

“He is the richest who has most use for nature as raw material of tropes and symbols with which to describe his life,” wrote Thoreau, age 35, in his journal. This is a lesson well worth imparting. Another treasure nature provides in superabundance is perspective. If California’s megalophobia-inducing Redwoods seem large to you, consider them from the perspective of a banana slug. If a day seems too short — it is certainly too short to take in a national park — spare a thought for those creatures who experience it as a lifetime. If a lifetime seems too long, reckon it against the glacial advance of geologic time, which will help you justify the insane driving distances between points of interest at the larger parks.

If nature bores because it seems devoid of human activity, keep in mind that it hasn’t always been so. Most of the wild places we protect have been sites of human exploration and habitation, which means they possess a rich, hair-raising history of survival and defeat. What was it like to endure these environments before we’d been herded into cities and suburbs? How were they traversed or tamed? Our parks still swallow up tourists and hikers on a regular basis. Fear may be the most effective means of cultivating respect for the natural world, as the success of films such as 127 Hours and The Revenant attest. If your children aren’t contemplating their mortality at a national park, under threat of rattlesnake bites, flash floods, and suffocating, bone-crushing avalanches, you’re missing an opportunity. The forest shouldn’t be the only thing that’s petrified.

To look out at nature and say, as one of Share’s unhappy campers did, “Give it a miss,” isn’t proof of a character flaw. It doesn’t mean you’ve been irretrievably poisoned by civilization and its decadent distractions. Learning to be moved by nature is a lifelong process, and one hamstrung by grim political and economic debates. Nature, like classic literature, is more often praised than appreciated. Once, at a turnout in Yellowstone, I saw a man point out a treacherous prow of rock jutting over the canyon. “I bet loads of people go stand on that and get their picture made,” he remarked to his family. And then they stayed in the car, staring, level with the canyon’s lip, through the windshield.

“Quiet desperation,” Thoreau might cluck, savoring his supremacy among men. A more generous spirit recognizes that some people, at least at first, just need a firm shove in the right direction.

Stefan Beck is a writer living in Hudson, New York.