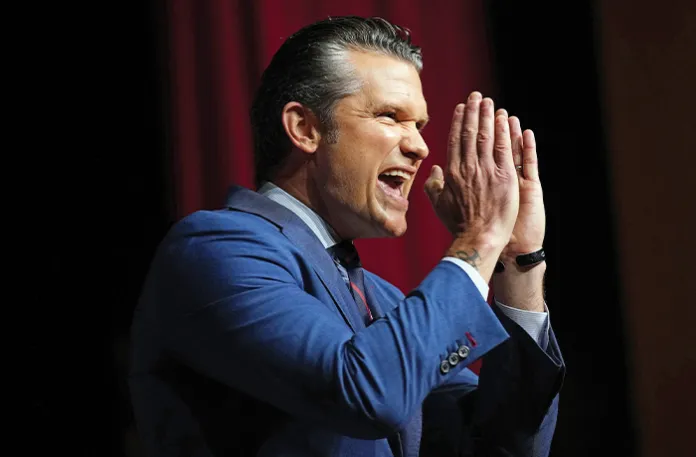

The unusual all-hands meeting of flag and general officers — FOGOs, or officers of one to four stars — convened by War Secretary Pete Hegseth at the Marine Corps base in Quantico, Virginia, has concluded. Much of the speculation about the purpose of the meeting has proven to be overheated. For instance, the worst-case scenario imagined by critics of President Donald Trump and the secretary — something like the “red wedding” scene from Game of Thrones: a mass purge of senior officers — did not materialize.

Neither did a discussion of the new “National Defense Strategy,” which is due to be published soon. He did not address the possibility of new regional priorities for the War Department, for instance, a shift from China and the Indo-Pacific theater to homeland security and hemispheric defense. He did not discuss possibly consolidating regional commands, e.g., recombining European Command and Africa Command and merging Southern Command and Northern Command.

But that did not assuage the concerns of those critics that their ultimate goal is to “politicize” the military by purging those who do not share the president’s vision regarding security matters. They point to the fact that the Trump administration has fired several flag and general officers since taking office in January, including former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr.; Adm. Lisa Franchetti, former chief of naval operations; Adm. Linda Fagan, former commandant of the Coast Guard; Gen. James Slife, former vice chief of staff of the Air Force; Lt. Gen. Jeffrey Kruse, former head of the Defense Intelligence Agency; Vice Adm. Nancy Lacore, former chief of the Navy Reserve; and Rear Adm. Milton Sands, former head of Naval Special Warfare Command.

Hegseth did confirm his intention, which he announced in May, to cut the number of four-star generals and admirals by at least 20%. Despite the claims of critics that this is another example of politicizing the officer corps, the top-heavy nature of the officer corps has been apparent for many years. For instance, in his classic 1986 study The Pentagon and the Art of War, Edward Luttwak observed that the United States achieved victory on multiple fronts during World War II with far fewer officers commanding far more troops and ships than is the situation today. The proliferation of commands and especially senior officer billets has coincided with a decline in strategic thinking and military performance, from Vietnam to Afghanistan. Hegseth recognizes that the U.S. military does not benefit from the bloat of senior officers.

Before the election, the Wall Street Journal published an article claiming that the Trump transition team had drafted an executive order that would “create a board to purge generals … which, if enacted, could fast-track the removal” of flag and general officers “found to be lacking in requisite leadership qualities.” But the outlet went on to say that it “could also create a chilling effect on top military officers, given the president-elect’s past vow to fire ‘woke generals,’ referring to officers seen as promoting diversity in the ranks at the expense of military readiness.”

The article implied that any attempt to remove flag and general officers from the U.S. military is, like Josef Stalin’s purge of the Red Army before World War II, ideological, aimed at eradicating officers deemed not sufficiently committed to Trump and his administration. Although Trump’s relationship with the senior leadership of the U.S. military has always been fraught, the charge that he is aiming to purge it of officers not sufficiently loyal to him is, at best, an overreach.

A better interpretation of such a board is that it is an attempt to restore accountability, something that has been missing in the U.S. military for some time. Writing in World Affairs in 2009, Richard Kohn, the dean of American military historians, observed that “nearly twenty years after the end of the Cold War, the American military, financed by more money than the entire rest of the world spends on its armed forces, failed to defeat insurgencies or fully suppress sectarian civil wars in two crucial countries, each with less than a tenth of the U.S. population, after overthrowing those nations’ governments in a matter of weeks.” What, he asked, accounted for this lack of military effectiveness?

In his 2012 book The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to Today, Tom Ricks, formerly of the Washington Post and Wall Street Journal, suggested an answer, arguing that many of the failures suffered by the U.S. military over the past decades could be attributed to the fact that the Army no longer held officers accountable for failures on the battlefield. During World War II, relief was a common occurrence. Gen. George Marshall, the “architect of victory” during that conflict, routinely relieved subordinates.

In the decades following the war, whatever reliefs did occur were executed by political leaders. And even then, many officers were simply “kicked upstairs,” as in the case of William Westmoreland in Vietnam and George Casey in Iraq. As one Army officer observed during the early phases of Operation Iraqi Freedom, “As it stands now, a private who loses a rifle suffers far greater consequences than a general who loses a war.”

An important point to keep in mind is that, although the president requires the consent of the Senate to appoint officers, he has the authority to fire them without congressional approval. And presidents have exercised this authority since the beginning of the republic. Indeed, in the case of Thomas Jefferson, he appointed officers for ideological reasons. It should be noted that the idea of a nonpartisan, professional officer corps is of recent vintage, dating only to the Progressive era at the end of the 19th century. When Jefferson became president, he set out to replace Federalist officers, who had dominated the Army since the revolution, with Republicans. Establishing the U.S. Military Academy was one means of accomplishing this end.

It is also the case that commissions such as the one suggested by the Wall Street Journal are nothing new in American military history. During the Civil War, Congress created the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, which investigated all matters affecting the conflict, including operational and tactical issues, as well as the performance of officers in the field. And prior to World War II, Marshall established a board led by retired officers to review officer records and “remove from line promotion any officer for reasons deemed good and sufficient.” The goal, of course, was to remove “dead wood” to make room for younger and more capable officers.

In fact, Hegseth used this face-to-face meeting to deliver his vision for the department. He has been a longtime critic of senior military leadership, arguing that too many FOGOs have subordinated warfighting to peripheral matters, most notably “diversity, equity, and inclusion,” which undermines military effectiveness and what Samuel Huntington called the military’s “functional imperative”: fighting and winning wars.

As I have argued before, diversity now trumps military effectiveness as a goal of military policy. But attempts by the military to address an alleged lack of “diversity” in the ranks can actually make things worse by pushing “identity politics,” which, by suggesting that justice is a function of attributes such as sex and skin color rather than one’s excellence, tends to divide people rather than unify them. Identity politics undermines military effectiveness, which depends on cohesion born of trust among those who operate together.

The military claims to be a profession. But all too often, it acts like just another self-interested bureaucracy. Hegseth believes that officers owe it to their profession and, more importantly, to the people to say publicly what most say privately: that bending the military ethos to the demands of identity politics undermines that ethos, reduces military effectiveness, and leads inexorably to a disaster on some future battlefield.

WHAT’S IN A NAME? THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE BECOMES THE DEPARTMENT OF WAR

Officers take an oath to the Constitution, not to an individual. But civilian leadership should have the right to expect that the officers will be loyal in terms of supporting policies. Civilian control of the military means that civilians make policy. Officers can recommend but not insist.

I can’t put the case for Hegseth any better than one of our foremost advocates of military reform, Donald Vandergriff, in Adopting Mission Command, who writes that what the secretary wants to do is necessary to address the “rot in our officer corps — bloat, risk aversion, and a culture more obsessed with HR checklists than warfighting.” He continues, “DEI? A Trojan horse for mediocrity, letting ‘truth tellers’ dilute standards while China and Russia laugh. Hegseth gets it. Lethality first.” The time for noncompliance or malicious compliance is over. The purpose of the meeting was to drive home a simple but powerful message: get on board or leave.

Dr. Mackubin Owens, a retired Marine and former Naval War College professor, is a senior fellow of the Foreign Policy Research Institute.