Romanticizing bloodshed, one would think, is not a very admirable thing to do, but the radical Left seems to have a penchant for it, from Che Guevara to chants of “pigs in a blanket” and from the Weather Underground to the Symbionese Liberation Army. Its latest case of glorifying such a troubling figure is Assata Shakur, the Black Panther dropout, Black Liberation Army gunwoman, convicted cop-killer, prison escapee, and enduring icon of “resistance” who died late last month in Havana at 78. Perhaps even more disturbing than the trail of violence she left in her life has been the trail of tributes that have greeted her death.

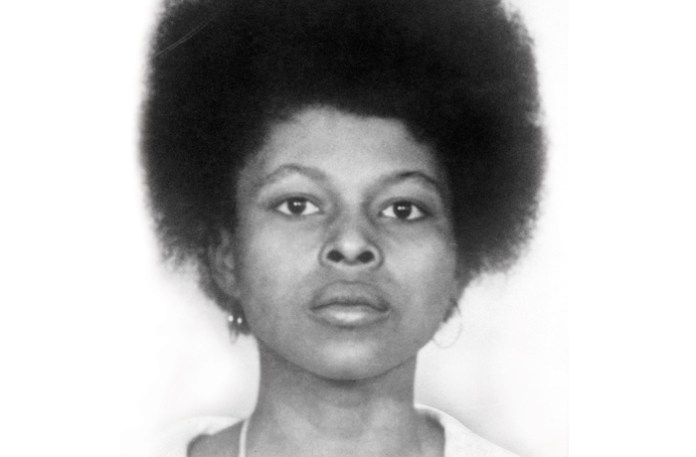

Born JoAnne Deborah Byron on July 16, 1947, in Queens, New York, raised partly in the South and back in New York by her teens, she dropped out of high school at 17, drifting through odd jobs and community college before the 1960s’ ferment pulled her in. A brief marriage to activist Louis Chesimard ended by 1970, freeing her to chase the era’s firebrands.

Shakur’s radicalization ignited in 1970 when she joined the Black Panther Party at its peak. Shakur patrolled Harlem with a .38, seeing cops as white supremacy’s vanguard. But the paramilitary party’s machismo and shallow history grated on her. “The Panthers made it clear who the enemy was,” she wrote in her 1987 memoir, Assata, “not white people, but capitalistic oppressors.” By 1971, she jumped to the Black Liberation Army, a Marxist-Leninist splinter group inspired by the Viet Cong, set on urban warfare against the “fascist state.”

The BLA’s campaign was brutal: bombing police stations, robbing banks for “the struggle,” killing dealers as “class enemies,” and ambushing police. Shakur, now Assata Olugbala Shakur, dove in. Her rap sheet screamed terror: murder, robbery, kidnapping, attempted murder. In 1971, she was nabbed for a Queens robbery. That same year, she faced kidnapping charges in Atlanta over BLA school bus seizures protesting Vietnam. Shootouts followed in the Bronx in 1971 and in Queens in 1972.

The climax came on May 2, 1973, on the New Jersey Turnpike. Shakur, in a Pontiac with BLA comrades Zayd Malik Shakur and Sundiata Acoli, was stopped for a taillight. Gunfire erupted: State trooper Werner Foerster died from a hollow-point to the head, Zayd was killed, and Assata took two bullets, collapsing, she claimed, with her hands up. Acoli fled; he’d later serve 40 years. Ballistics linked the fatal shot to a revolver with Shakur’s prints. New Jersey’s felony murder rule pinned her as a conspirator. Convicted in 1977 of murder, robbery, and assault, she got life plus 33 years, entering Clinton Correctional as prisoner No. 76-9-1234 — a symbol of state racism to some and of justice to others.

In prison, Shakur penned manifestos decrying “amerika’s” prison gulag. On Nov. 2, 1979, BLA gunmen stormed Clinton, took guards hostage, hijacked a bus, and freed her in a hail of bullets. She vanished underground, surfacing in Havana by 1984. Fidel Castro, who saw her as an anti-imperialist ally, granted her asylum. In Cuba, she worked for Radio Havana, taught English, and raised her daughter, Kakuya.

The Left further mythologized her during her exile. The FBI’s $2 million bounty — earning her the distinction of being the first woman on its most wanted terrorists list — cemented her infamy. Her ghostwritten memoir painted her as a framed victim. Hip-hop lionized her: Tupac and Common nodded to her. Black Lives Matter activists adorned their walls with her image.

The shock of Shakur’s death wasn’t its suddenness (she had reportedly been suffering from health problems) but the hagiographic eulogies. The New York Times called her a “tireless battler against racial oppression.” The Washington Post noted her “mythical status,” burying Foerster’s name under BLM chants. NPR suggested that her crimes were either uncommitted or justified. USA Today hailed her memoir as “seminal,” ignoring the trooper’s blood. Harper’s Bazaar dubbed her a feminist “lodestar.” People called her a hip-hop “folk hero.” Rolling Stone marveled at her duality. The BBC cited her rap shout-outs. BLM Grassroots gushed: “May her courage guide us.” Amid the recent upsurge in political violence — the murder of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, the killing of Minnesota legislators, the torching of Gov. Josh Shapiro’s (D-PA) residence, the killing of Israeli Embassy staff members, and the near-assassination of President Donald Trump — these outrageous tributes threaten to inflame even more outrage, especially coming as they are mere weeks after the assassination of Turning Point USA founder Charlie Kirk.

As prosecutors seek the death penalty for Kirk’s alleged killer, these repugnant tributes reveal a rot: One side’s terrorist is another’s hero. Violence is sanctified if the target espouses the “wrong” ideas” or wears the wrong things, like a police badge (or a MAGA hat). Even in this age of profound political polarization, we should be able to agree that neither murder nor political violence of any kind is ever acceptable, no matter which side is being targeted and no matter what the target may have said to “provoke” it. And can’t we all agree that those who engage in political violence should be condemned for it, not praised?

Daniel Ross Goodman is a Washington Examiner contributing writer, the author of three books, and the Allen and Joan Bildner Visiting Scholar at Rutgers University.