In her 1992 memoir Curriculum Vitae, the novelist Muriel Spark describes her childhood neighbor in Edinburgh named Nita McEwen. Spark and McEwen did not know each other well, but their “physical resemblance was often remarked upon.” Years later, Spark encountered McEwen in southern Rhodesia, where both young women were living with their husbands. Spark’s new marriage was unhappy, but McEwen’s was worse: her husband murdered her, then killed himself. Spark used this event as the basis for a short story.

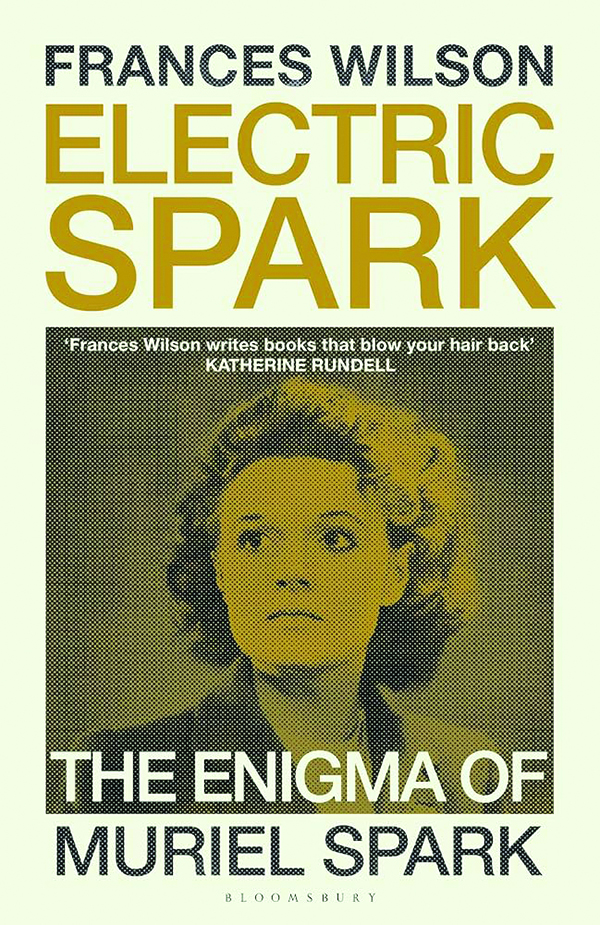

But Frances Wilson isn’t buying it. In her research for Electric Spark: The Enigma of Muriel Spark, the biographer found no news accounts of the murder-suicide, nor any evidence of McEwen’s birth, schooling, or existence. She posits the doppelganger is a figment of Spark’s imagination, a vision of what her life might have been like if she hadn’t left her first husband. It’s also a manifestation of Spark’s love for word puzzles and the plot device of doubling: McEwen is an anagram for Twin Menace. Wilson’s sleuthing captures Spark’s elusive and fascinating character, as well as the biographer’s familiarity with the great novelist’s habits, interests, and techniques.

Spark, born Muriel Camberg in 1918, did not publish her first novel until she was 39 years old, and was not wealthy and famous until the early 1960s. But Wilson isn’t interested in Spark’s prime; she wisely explores the lean and formative years, when Spark struggled as an editor, critic, and poet. Spark’s life was certainly more varied and tumultuous before she settled into a career as a novelist.

Spark was born and raised in Edinburgh, the working-class daughter of a Jewish factory worker and a Christian piano teacher. She described herself as a “Gentile Jewess,” one of many expressions of her doubleness. In her late teenage years, Spark met an older man named Sydney Oswald, or “Ossie,” and together they moved to southern Rhodesia to get married. Adjusting to life away from home would have been difficult enough with a mentally stable husband, but Ossie was not that. They had a son, Robin, in 1938; divorce proceedings and World War II started the next year. Spark left Ossie and Robin for Cape Town, South Africa, in 1943 — Wilson posits the tantalizing possibility that she was working as a British spy by then — and then secured a berth to England in 1944. Robin would journey to Britain the following year and live in Edinburgh with Spark’s parents.

In London, Spark found a job with the Foreign Service in the Political Warfare Executive, working in the dark arts of anti-Nazi propaganda and disinformation. Wilson presents the director of this agency, Sefton Delmer, as an omniscient entity overseeing an array of intelligence, the precursor of her best-known character, Miss Jean Brodie (who was based most directly on one of Spark’s schoolteachers). Wilson rightly connects Spark’s time in the agency to her subsequent fascination with secrecy, blackmail, and linguistic codes.

Pursuing a literary career after the war, in 1947 Spark became the editor of Poetry Review, a journal published by a stuffy literary organization called the Poetry Society. She tried to reshape the institution with editorials that defended modern poetry and by paying contributors instead of accepting payment from them. The journal took on what Wilson calls an “Edinburgh Character,” comparable to the great romantic-era literary journals of the Edinburgh Review and Blackwood’s Magazine.

Although Spark did not live in Edinburgh after her teenage years, she never shook the city’s influence. Her poetic sensibilities, as well as her interest in ghosts, doubles, and blackmail schemes, were shaped by Scottish ballads and tales. “Doubleness was part of her heritage,” Wilson says, and she inherited the spirit of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Jekyll & Hyde and James Hogg’s The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner.

After her inevitable firing from Poetry Review, Spark found work as a secretary and assistant for a series of publishers and organizations. For some time, Spark’s interest in doubleness meant she enjoyed working with Derek Stanford, who doubled as her lover. They wrote poems together, kept a diary, and co-authored several books in the 1950s, including an edition of Mary Shelley’s letters and one of John Henry Newman’s. That same decade, Spark published several critical works of her own. A strength of this biography is that Wilson gives serious attention to how Spark’s interest in these writers shaped her own understanding of herself as a poet and critic.

Stanford played a major role in Spark’s life, for better and worse. He nursed her in bad health; he also stole some of her papers and sold them once she became famous. He wrote a critical biography and a gossipy memoir about her. When Spark chose Martin Stannard to write her biography in the 1990s, she hoped he would eviscerate Stanford and was furious when he did not. Stanford/Stannard — another double, as Wilson points out.

While still working with Stanford, Spark felt the pull of religious belief and was baptized in an Anglo-Catholic church in 1953. This spiritual conversion was accompanied by a mental breakdown, psychotic episodes induced by taking an over-the-counter weight-loss medicine. Disembodied voices spoke to her. Secret codes appeared in the work of T.S. Eliot. A friend referred to her condition as “an attack of paranoia.” The condition lasted until April 1954; she received her first communion in the Roman Catholic Church the following month. Before long, she was at work on her first novel, The Comforters, a fictionalized version of her conversion and psychotic break.

Spark would frequently return to these pre-fame years in her fiction, including some of her best-known works: The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961), The Girls of Slender Means (1963), Loitering with Intent (1981), and A Far Cry from Kensington (1988). Wilson tells us that “Spark’s imagination worked in patterns,” and her novels include books within books and complex reworkings of her past. Wilson enjoys pointing out uncanny coincidences and surreal similarities, indulging in the belief that events in Spark’s life were foreordained in a manner that Spark herself liked to make the events in her novels feel. Wilson observes, “the operation of time, in Muriel’s world, had long ceased to be chronological.” And so it is for Wilson, who leaps ahead decades to incorporate references from novels that enlighten Spark’s meanings and experiences.

Spark had the reputation for writing her novels quickly and without much effort, but Wilson sifts through the archives to show that her process was more complicated and painstaking. For The Girls of Slender Means, in which short passages from a character’s journal play an important role, Spark had written a draft of the entire notebook as background.

SPINAL TAPPED OUT: A REVIEW OF ‘SPINAL TAP II’

Spark could be a difficult person. Wilson calls her “the loneliest and most singular figure on the twentieth-century literary landscape.” Her detachment from Robin is especially hard to swallow: she supported him financially, but left his upbringing to her parents. Many of her friends distrusted her, and she seems to have grown increasingly snobbish as her fame and wealth increased. “Envy and jealousy corrode and destroy,” Wilson writes, “but without them Spark could not write: this is her secret.”

Such claims make it unlikely Spark would have approved of Wilson’s biography, but then she probably wouldn’t have authorized anything short of hagiographic score-settling. Nonetheless, Wilson has written a remarkable life of this important author, one that offers keen insights into her subject while also imitating Spark’s penchant for patterns and stylistic flair. It is as clever and full of surprises, including a dedication to the aforementioned McEwan, as the novelist to whom it does justice.

Christopher J. Scalia is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and the author of 13 Novels Conservatives Will Love (but Probably Haven’t Read).