Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUU) endangers fisheries across the globe that contribute to economic growth, food systems, and ecosystems, and the Trump administration is trying to crack down on violations in the Gulf. The Washington Examiner traveled to the South Padre Island and Air Station Corpus Christi to ride along with the Coast Guard during a boat patrol tour and take a daily overflight tour of the Deep Gulf. Installment one of In too deep: Illegal fishing in the Gulf – and the Coast Guard’s action plan explores why illegal fishing is such a big problem.

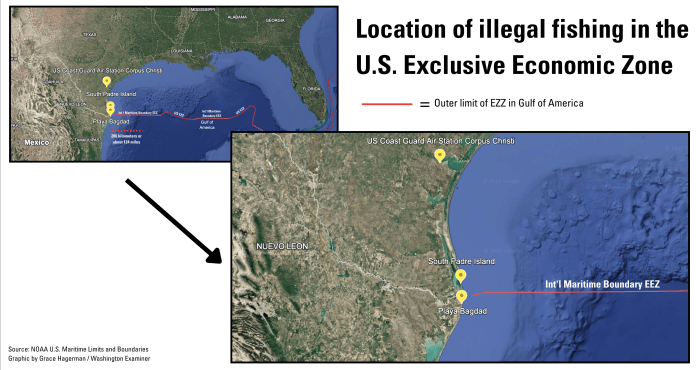

CORPUS CHRISTI, TEXAS — Despite heavily regulating both commercial and private fishing in the Gulf of America, the United States loses millions of dollars every year to the illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUU) that occurs in the U.S Exclusive Economic Zone in the Gulf of America by Mexican fishermen.

Commercial and recreational fishing in the Gulf is a multimillion-dollar business managed at the state and federal levels. By far, the most common fish is red snapper. The Gulf Council, one of eight U.S. Regional Fishery Management Councils that oversees fishery resources in the federal waters of the Gulf of America, set the 2025 annual catch limit at slightly more than 16 million pounds of red snapper.

The strict U.S. regulations mean more fish are available in U.S. waters than in Mexico’s waters, where fishermen do not have restrictions to follow designed to preserve the environment.

How big an industry is red snapper fishing in the Gulf?

In 2024, commercial fishermen caught roughly 8 million pounds of red snapper valued at more than $42 million in the Gulf, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. But a key unknown is how many fish Mexican fishermen catch illegally in U.S. waters, and the monetary value U.S. fishermen are losing out on.

In April, the U.S. Trade Representative said, “Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing undermines America’s competitiveness and costs the global seafood industry up to $50 billion per year.”

The U.S. imported about $2.4 billion worth of seafood from IUU fishing in 2019, according to a 2021 report from the U.S. International Trade Commission, which estimated that the removal of IUU fishing could increase the total operating income of the U.S. commercial fishing industry by an estimated $60 million.

The Harte Research Institute at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi is working on a project with the Coast Guard and other agencies to resolve the information gap about exactly how many fish and how much profit the U.S. is losing out on to Mexican fishermen.

“This project specifically is going to look at how many fish are being removed from U.S. waters and taken back to Mexico. This will also allow us to put a dollar amount on the fish to see how it’s impacting our economy,” Dr. Kesley Banks, an Associate Research Scientist from the Harte Institute, told the Washington Examiner. “They are taking a cut that is not being accounted for.”

The Coast Guard “tells us how many times they’ve caught this illegal fishing happening, but that was never done to an estimate, so we don’t know exactly how many fish, we just know how many incidents happen,” she explained.

The service also provides samples of the fish they seize on lanchas, the single-engine boats used by Mexican fishermen, to the team at the Harte Research Institute to be researched.

By the end of their research, Banks hopes to have “an estimate of how many fish are leaving U.S. waters, and we will have an economic dollar value for each of those fish between the sectors.”

In July, the Senate passed by unanimous consent S. 283, the “Illegal Red Snapper and Tuna Enforcement Act,” which would require agencies to develop a system for determining the origins of caught fish to determine “the country of origin of seafood to support enforcement against illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, and for other purposes.”

Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) said, “This legislation will crack down on cartels & other criminal entities that are illegally catching, importing, and selling fish to unwitting consumers.”

Coast Guard works to enforce strict fishing regulations

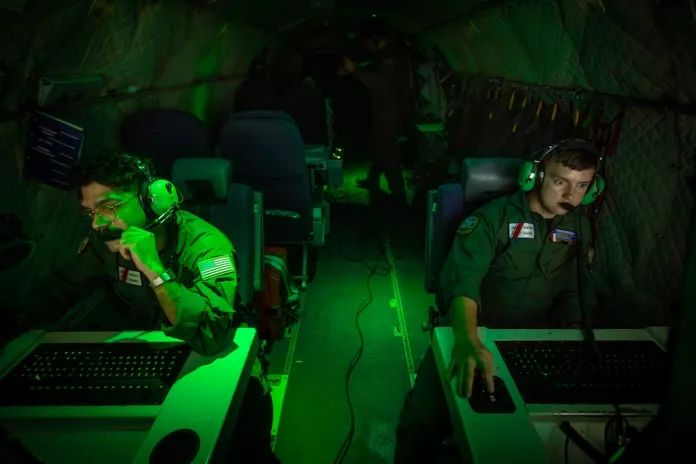

The Coast Guard is the primary law enforcement agency that will interdict Mexican fishermen caught fishing in U.S. waters. They are identifiable by their boats, called lanchas, and are carbon copies of one another. The single-engine white and blue boat is cheaply made because the producers know the risk that U.S. forces could seize the vessel.

The Coast Guard aimed to interdict 40% of all detected vessels encroaching on the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone but failed to meet that goal by almost half during the Fiscal Year 2023 and Fiscal Year 2024, according to a Department of Homeland Security Office of the Inspector General report from June. They interdicted 116 of the 546 detections that occurred during that time period.

U.S. Coast Guard Station South Padre Island, which is located only about six miles north of the Mexican border, has carried out 46 interdictions of Mexican vessels dating back to the start of last year, seizing more than 11,200 pounds of fish. There’s no estimate, however, of the quantity of fish caught that were returned to Mexico by the fishermen.

The Mexican fishermen who fish in U.S. waters often leave from Playa Bagdad, right by the U.S. border, and their operation is tied to the Gulf Cartel, according to the Treasury Department. Last November, they sanctioned five people “tied to the Gulf Cartel’s involvement in criminal activities associated with IUU fishing, human smuggling, and narcotics trafficking in the Gulf of Mexico.”

Ismael Guerra Salinas and his brother Omar Guerra Salinas are the Gulf Cartel members in charge of Playa Bagdad, and both of them were among the people the Treasury Department sanctioned last year. Two of the others were Raul Decuir Garcia and Ildelfonso Carrillo Sapien, whom the department said are lancha camp owners who oversee and enable illegal fishing in U.S. waters.

One way Mexican fishermen try to increase their intake is by setting up longlines with dozens or hundreds of hooks on them, placing the contraption in the water to return to it later, hoping to have a significant number of fish hooked and waiting for them.

The Gulf Cartel is a drug trafficking organization that operates in Tamaulipas State, Mexico. They’ve allegedly been involved in the smuggling of arms, drugs, and migrants into the United States, and were responsible for the kidnapping and murder of two American citizens in March 2023.

How IUU fishing differs from legal fishing

There are specific limits on the number of pounds of fish private, commercial, and for-hire fishermen can catch and the number of days they are allowed to fish, while any fish caught illegally reduces their shares.

Of the 16 million pounds of red snapper the Gulf Coast has set for the 2025 catch limit, 51% of that total is designated for commercial fishing, 28% for private recreational fishing, and the remaining 21% is for federal for-hire fishermen.

This year, the for-hire fishermen who lead charters were only eligible to work from June 1 through mid-September, while the private recreational season is determined at the state level for each Gulf state.

The Mexican fishermen who overfish in their waters and wade into U.S. waters do not abide by these regulations.

“Having these fish illegally removed hurts everyone. It decreases your days as a private citizen to go fishing, it hurts the federal for-hire who’s taking tourists that come down, it hurts hotels because you no longer have fishermen coming down. It hurts commercial [fishermen] who’s catching fish and selling them back to the U.S.,” Banks added. “So when they go through Mexico, you get this inferior product that floods the market, and with that comes decreased prices on red snapper.”

Each lancha will routinely catch hundreds of pounds of fish.

Real-life effects of illegal fishing

Four Mexican fishermen were charged earlier this year with illegal fishing inside the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone. They had deployed about four miles of longline containing approximately 1,200 hooks. The charges marked the start of a more aggressive approach from the U.S. to stop illegal fishing by charging the fishermen, and there has been a decrease in interdictions since then.

U.S. Coast Guard Station South Padre Island has carried out 15 interdictions this calendar year, compared to 31 last year, and only four of the interdictions this year have occurred since June 1, about two weeks after the Department of Justice indicted the four fishermen.

QUARTER-MILLION AMERICANS HAVE APPLIED TO ICE AND BORDER PATROL UNDER TRUMP

Capt. Scott Hickman, a retired Marine and now a for-hire recreational fishing guide who sits on the Gulf Council, told the Washington Examiner, “It’s crazy that it’s gone this long so out of control on such a valuable natural resource.”

Hickman, who is based in Galveston, Texas, a couple of hours further north than South Padre Island, said he hasn’t encountered clearly identifiable illegal fishermen in U.S. waters, but he’s “come across their gear.”

For Hickman and other for-hire recreational crews, the number of days they can take groups out on the water directly impacts their livelihoods. His plight is similar to that of others who benefit from the fishing tourism industry, such as hotels and restaurants.

The Mexican fishermen often ultimately sell the fish back into the United States, which poses health concerns, Banks said, because they often do not put the fish on ice like American fishermen would.