In the annals of boxing’s greatest heavyweight champions, two names often enter the conversation: Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney. They each had Irish backgrounds, were ring-savvy, had real punching power, and rarely lost. Their two titanic battles were highly anticipated events in the Roaring Twenties.

Even though nearly a century has passed since they fought, “their combined glitter captured the minds of and elicited roars from fans of the sport in the 1920s and the spotlight has never really worn off,” writes Lew Freedman in his compelling new examination of this memorable rivalry, Dempsey and Tunney in the Roaring Twenties. An author and sportswriter for newspapers such as the Anchorage Daily News, Chicago Tribune, and Philadelphia Inquirer, he depicts them as a “duo, linked together, almost as one.”

The book places the pantheon of boxing alongside other 1920s-related sporting events, including the rise of the NFL, Man o’ War and horse racing, and tennis stars such as Suzanne Lenglen and Bill Tilden. Chapters are devoted to Charles Lindbergh “flying solo” across the Atlantic and the “disgraceful racial hatred” of black boxing champions. But the main focus is Dempsey and Tunney, two exceptional heavyweight champions with distinct backgrounds and personalities. Dempsey was a “people person” and “more at ease with fans,” while Tunney was “aloof” with a “deep commitment to reading literature.”

William Harrison Dempsey was born in June 1895 in Manassa, Colorado. Harry, as he was called, first competed as “Kid Blackie” and “Young Dempsey.” He became “Jack” Dempsey when he replaced his older brother, Bernie, in a 1914 fight against George Copelin. No matter what he was called, Dempsey was a great fighter and showman. He emulated the legendary bare-knuckles heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan by “waltzing into gyms” and proclaimed he could “lick any one of them.” He possessed “fists of thunder with a bazooka’s knockout capacity.” He lost fights to Jack Downey, Willie Meehan (twice), and Fireman Jim Flynn, but beat them all in rematches. His biggest moment was against heavyweight champion Jess Willard in 1919, who had defeated the first black champion, Jack Johnson. Dempsey, a “no mercy guy who understood that the law of the ring was that the other guy was out to get you, so you’d better be out to get him,” dominated the taller and more experienced Willard. The fight was “total destruction from start to finish,” and a new champion was crowned.

James Joseph Tunney was born to Irish immigrants in May 1897 in New York City. He took the name “Gene” because his younger sisters had “difficulty pronouncing James.” He was a “bookworm” who not only “read more Shakespeare than the sports pen men, but he could also quote it.” Tunney was also a skinny child, so his father bought him boxing gloves and taught him the art of pugilism. His parents hoped he would give up boxing for the priesthood, but their prayers weren’t answered.

Tunney was inspired to “build up his physique” by President Theodore Roosevelt, “a champion of physical fitness.” He boxed during his wartime stint in the Marines. He beat light heavyweight greats Barney “Battling” Levinsky and Georges Carpentier. The only boxer who ever defeated him was Harry Greb, a talented fighter in spite of being relatively short and “blind in one eye.” Tunney beat Greb in several rematches, but praised his rival and stated, “[H]e was never in one spot for more than half a second … it was like fighting an octopus.”

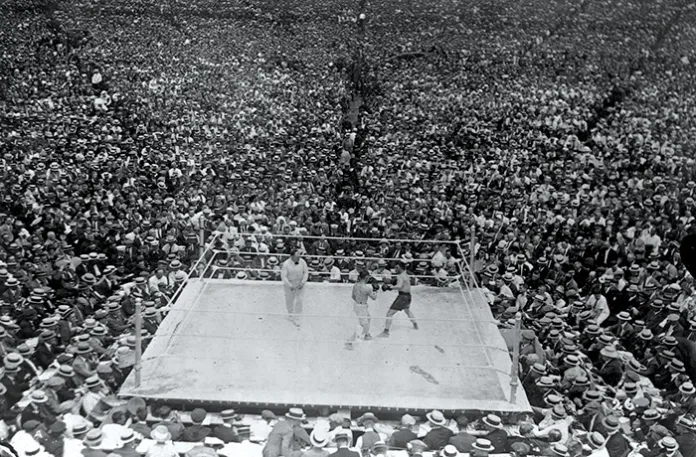

The most intriguing sections of Dempsey and Tunney in the Roaring Twenties relate to their two fights and an unforgettable delayed count. The first bout occurred on Sept. 23, 1926, at Philadelphia’s Sesquicentennial Stadium in front of 120,557 people, including luminaries such as Babe Ruth and Charlie Chaplin. Dempsey was the favourite, but he was outboxed and outsmarted by Tunney. The title changed hands on a 10-round unanimous decision. Both men were gracious to one another, but sportswriters didn’t shower the winner with glory. “More alibis for Dempsey appeared in print than positive notices for Tunney’s star turn,” Freedman writes.

The second bout occurred at Chicago’s Soldier Field on Sept. 22, 1927. Dubbed the “Battle of the Century,” it was witnessed by 104,943 fight fans. Tunney kept his distance from Dempsey and dominated the first six rounds. Then came “The Long Count,” in which Dempsey knocked out Tunney in the seventh round but didn’t go to a neutral corner. It was a new boxing rule that Dempsey wasn’t used to and likely forgot. “Tunney was down from anywhere between 13 and 18 seconds,” which gave him enough time to beat it.

MAGAZINE: THE ETERNAL ARGUMENT OVER WHAT IS AND ISN’T A SPORT

Dempsey never recovered. He was knocked down by Tunney in the eighth round and, in a twist of irony, referee Dave Barry started counting before Tunney moved to a neutral corner. He held on and finished the fight. The result was another 10-round unanimous decision for Tunney. Yet, his image as an odd duck and bookworm persisted, whereas Dempsey’s popularity rose in defeat. The Manassa Mauler would always be the people’s champion.

Dempsey and Tunney retired in 1927 and 1928, respectively. The old rivals later became friends. Dempsey even campaigned for Tunney’s son, John, when he successfully ran for the U.S. Senate. But as Freedman’s excellent book shows, there was only room for one member of boxing “royalty” in the Roaring Twenties — and that was Jack, not Gene.

Michael Taube, a columnist for National Post, Troy Media, and Loonie Politics, was a speechwriter for former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper.