Books on the politics of literary works can go wrong in at least two ways: They can reduce the significance of a literary work to the politics of its author or time (and great works are always about more than mere politics), or they can read today’s politics back into the original work, saddling authors with ideas that would be entirely foreign to them. Admirably, the critic Morten Høi Jensen avoids both of these errors in The Master of Contradiction: Thomas Mann and the Making of “The Magic Mountain” as he retraces the personal and political contexts of Mann’s most famous novel.

The Magic Mountain was an immediate if surprising success when it was first published in 1924. It is over 800 pages long in the original German and is composed mostly of long philosophical dialogues stitched together by the thinnest of plots. Mann promised to send a copy to French author André Gide but told him, “I do not in the least expect you to read it.” It is “highly problematical,” very “German,” and “of such “monstrous dimensions that I know perfectly well it won’t do for the rest of Europe.”

Yet, its initial print run of 20,000 copies sold out in three months despite appearing at the end of a catastrophic period of hyperinflation in Germany that impoverished millions. By 1928, it had sold over 100,000 copies in Germany and had been translated into French, English, Danish, Swedish, Hungarian, Polish, and Czech. When Mann won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929, the committee wrote that Mann had won “principally for this great novel, Buddenbrooks,” published nearly 30 years earlier, but the success of The Magic Mountain and Mann’s move from staunch critic to eloquent defender of democracy likely played a role, as well.

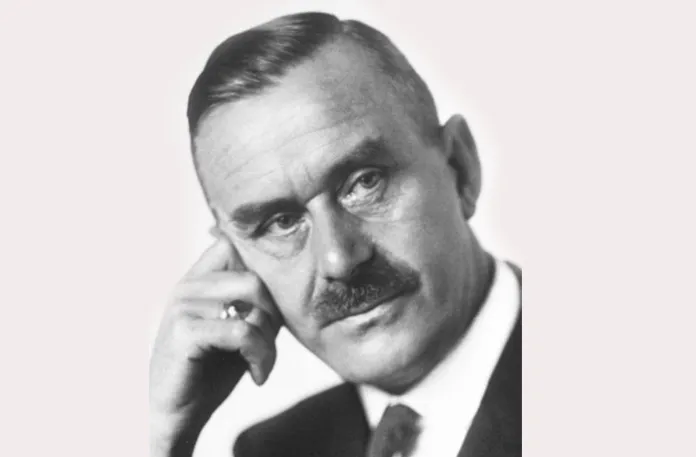

Germany’s humiliating defeat in World War I and the subsequent rise of fascist groups in Munich, where Mann lived during and after the war, had a significant effect on both Mann and the direction of his novel. Yet, Høi Jensen is careful to avoid overstating this influence. The Magic Mountain may be a “a kind of Bildungsroman [a literary coming-of-age genre],” Mann wrote to a friend in 1922, “in which a young man [before the war] is led by the experience of sickness and death to the idea of man and the state,” but it is also a novel about the nobility and difficulty of choosing life over death, love of others over solipsism.

Mann conceived of The Magic Mountain shortly after visiting his wife, Katia, in the Waldsanatorium in Davos in the spring of 1912. Frequently ill, Katia went to Davos on the recommendation of her doctor, who suspected she had contracted tuberculosis (she hadn’t, it was later discovered). Mann visited her and also became ill, like Hans Castorp in The Magic Mountain. He was preoccupied with death his whole life and associated illness with art. “Physical suffering seems to me an almost necessary concomitant of greatness,” he wrote. “I distrust pleasure, I distrust happiness, which I regard as unproductive.” It is by absorbing the suffering of life that the artist in turn creates something beautiful, something whole.

Yet, he had originally planned for The Magic Mountain to be a short, comical account of a young man caught between the “bourgeois decorum and macabre adventure” of a Davos sanatorium. In contrast to Mann’s 1912 novella Death in Venice, Høi Jensen writes, The Magic Mountain was to be “light and humorous – a satirical companion to its gloomier cousin.”

But then war intervened. Mann set the work aside and returned to his long and acrimonious feud with his brother over politics. Heinrich Mann was a progressive novelist and a “passionate democrat of the newest stamp,” as Mann put it. Mann, by contrast, thought democracy a “poison,” at least to Germans. “Whoever would aspire to transform Germany into a middle-class democracy in the Western-Roman sense … would wish to take away from her all that is best and complex,” Mann wrote in Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man (1918), which is best understood as a response to Heinrich’s 1915 essay praising Émile Zola’s democratic liberalism. Democracy, Mann wrote, would make Germany “dull, shallow, stupid.”

To Mann, his brother’s naive progressivism and sensationalist fiction were of a piece. Both failed to take suffering, a touchstone of reality for Mann, seriously. In his notebook, Mann wrote of his brother that “I consider it immoral to avoid the discomforts of indolence by writing one bad book after another.” “As a novelist,” Høi Jensen writes, “Mann felt it is his duty to describe the whole truth about existence. From the previous century’s writers – Tolstoy, Turgeneve (sic), Flaubert, Fontane, Ibsen, Jacobsen – he had inherited what he called a ‘truthful, blunt, and unfeeling submission to the real and the factual.’”

Yet, shortly after Mann picked up the novel again in 1919, he changed his view of democracy and eventually reconciled with his brother. While he did not support the violence of various revolutionary movements and coups in Germany at the time, he wrote in his diary that he would be “glad if something is achieved on the political plane, assuming good sense and order were followed and the conservative ideal is not compromised.”

“As the bodies kept piling up,” Høi Jensen writes, “any hope that German conservatism would not be compromised by the violence of the far right looked more and more naïve.”

After the German foreign minister Walther Rathenau was assassinated in 1922, Mann had had enough. In a speech later that year, Mann denounced the “sentimental obscurantism” of revolutionaries who were ruining the country with their “disgusting and crackbrained assassinations.” Previously, “sentimentality” was a term Mann had used to critique his brother’s progressive liberalism. Now, he used it to describe those who opposed the Weimar Republic.

Mann was also working through his ideas on democracy in The Magic Mountain by pitting the humanism of Ludovico Settembrini against the reactionary ideas of Leo Naphta. “Against Settembrini’s bourgeois humanism,” Høi Jensen writes, “Naphta hears the coming ‘newer, less namby-pamby social concepts, ideas of submission and obedience … The mystery and precept of our age is not liberation and development of the ego … What our age needs, what it demands, what it will create for itself, is terror.’”

MAGAZINE: A WORLD TOUR OF CHRISTIANITY

Høi Jensen argues that these dialogues allowed Mann to accept democracy, if not progressivism, as compatible with what he regularly called “the German soul.” Regardless, what is so powerful from a literary point of view in the second half of The Magic Mountain is how convincing Naphta is in his critique of liberalism, and yet how terribly wrong he is in his final solution.

The Master of Contradictions is an exemplary work of historical criticism. Høi Jensen shows with great nuance that “the writing of The Magic Mountain is a tale of two Thomas Manns” without ever obscuring that it is also a great deal more than this.

Micah Mattix is a poetry editor of First Things.